- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Jimmy’s Vendetta

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

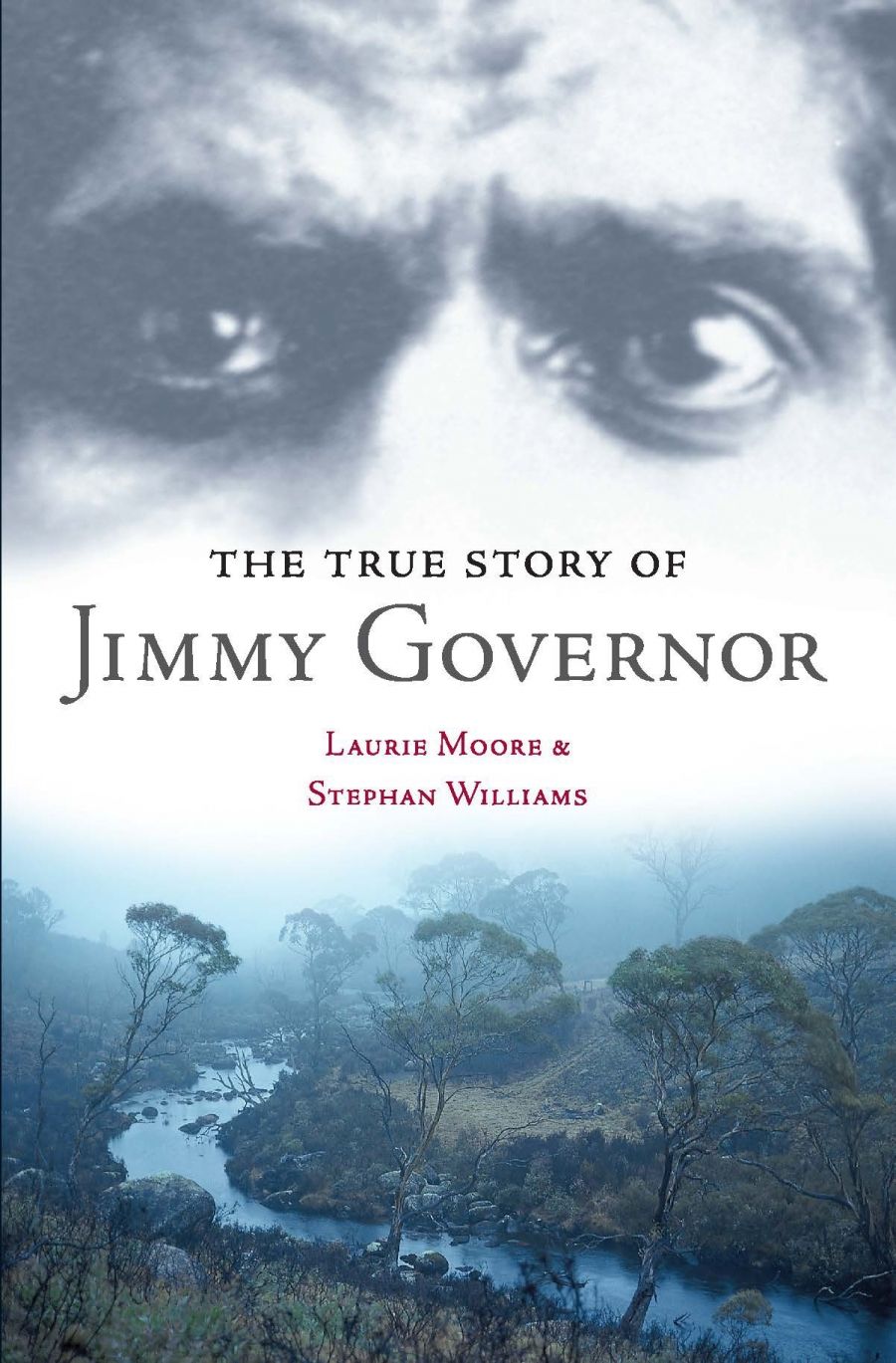

Five of Laurie Moore’s ancestors were in the party that finally captured Jimmy Governor in October 1900, ninety-nine days after his murderous onslaught on the Mawbey family. He and his wife have assiduously traversed the terrain of the manhunt for Jimmy and his brother Joe. Moore’s book, The True Life of Jimmy Governor, written in conjunction with Stephan Williams, is an admirable amateur labour: loving, painstaking, yet never without a tinge of irony about fashions of remembering folk anti-heroes in Australia. As the authors remark near the end of their story: ‘the brothers held up, or were fed by, everyone’s great aunt or grandfather’.

- Book 1 Title: The True Life of Jimmy Governor

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $24.95 pb, 240 pp

Hearsay takes too large a role in the evidence that Moore and Williams deploy, perhaps not least because – they contend – the story is ‘embedded deep in the psyche of generations of country people’. Take the case of Jimmy’s parents. His father was a man who did not enjoy the company of fellow Aboriginals and often quarrelled with them. Here is anticipated the life of his son, a man who lived between two worlds and was preyed upon by both. (This is the interpretation of Thomas Keneally’s bestselling novel, The Chant of Jimmie Blacksmith, a work mentioned once in passing by Moore and Williams; the film of the book gets no mention at all.) We read that ‘some of his family … believed he had been murdered by three Aborigines from Wollar’. But was he? We are left with supposition only. And what of Jimmy’s mother? In one of the haunting sidelights in this book, she is presented as the child of an Aboriginal servant and an Irish stockman. Her lustrous head of red hair was passed on to Jimmy, further marking him out in both the black and white communities. As a child, she was investigated by police out of a Victorian father’s desperate hope that she might have been his lost child, Eugenia Brooks. She was not. Her next appearance is in a footnote which plangently recalls her puzzlement, after their deaths, at what became of her two quiet sons.

Concentrating on the day-to-day pursuit of the Governors, Moore and Williams are at their strongest as storytellers, at the same time as they occlude the crucial question: what was the motivation for the series of killings, robberies and rape which the brothers committed? We get no more answer than that suggested above: the resentment of an intelligent man uncomfortably lodged, socially and psychologically; driven at last to a disproportionate revenge for slights against his white wife, who then turned into the perhaps heroic embrace of an outlaw fate: ‘Jimmy stayed in his country, for a brief period, a black man in charge of his own destiny.’

The most remarkable aspect of The True Life of Jimmy Governor is the account of how much contact Joe and Jimmy had during their flight. In the first sixty-seven days, they travelled 3200 kilometres, committed seventy-nine crimes, including murder, fired frequently at civilians and the police, robbed thirty-three huts and homesteads, were ‘seen by or came into contact with their pursuers on all but three of those days’. A collection of small-scale, clearly presented maps suggests the intimacy of that pursuit, how close to their trackers they almost always were. Treading in each other’s footsteps, walking the train lines, Jimmy and Joe long evaded capture. At the same time, they seem to have courted other contact, whether from victims or sympathisers, taunting police, accepting or insisting on assistance from outback workers like themselves, publicising their presence.

The True Life of Jimmy Governor ends with an admission of its own incompleteness. The authors regret ‘being unable to include the views or information of some who have personal knowledge of Jimmy’s story’. Whatever that means: it hints at secret business that would have been better not mentioned. There are hardly eyewitnesses to be produced. Nor has the book confronted its darkest implications. Will a ‘true life’ turn Jimmy into the hero for all or part of Australia that he has not yet succeeded in becoming, a role for which he has not so far been co-opted? Not yet a figure of myth, he can hardly benefit, or suffer, from modern re-mythologising. He remains a liminal, elusive figure, a metaphor for his own dexterity in avoiding capture for so long. Moore and Williams have constructively begun a process of our reacquaintance with the Governors, whose end remains uncertain.

Comments powered by CComment