- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Military History

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Stolen Youth

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

These are two quite different books about two quite different aspects of Australia’s involvement in the air war of 1939–45. Andrew McMillan, in Catalina Dreaming, describes in an effective, episodic manner what the war was like for the aircrew and ground staff of the RAAF who flew, serviced and maintained the Catalina flying boats. These aircraft were operated from Northern Australian bases over long expanses of water against distant Japanese targets. McMillan presents a colourful account of what it was like being involved in the war fought from areas such as Little Lagoon, the Qantas Base on Groote Eylandt opened in 1938, or Melville Bay in the Gulf of Carpentaria.

- Book 1 Title: Nicky Barr, an Australian Air Ace

- Book 1 Subtitle: A story of courage and adventure

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $24.95pb, 252 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

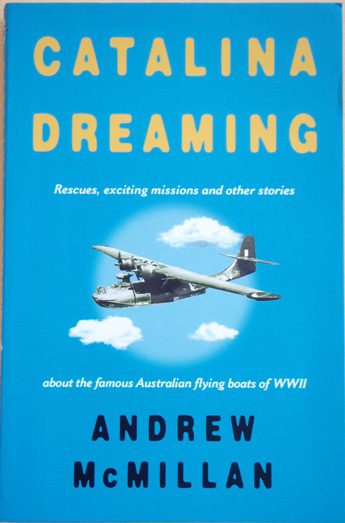

- Book 2 Title: Catalina Dreaming

- Book 2 Subtitle: Rescues, exciting missions, and other stories

- Book 2 Biblio: Duffy & Snellgrove, $21.95pb, 200 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

The Consolidated Catalina, the hero of McMillan’s book, came into American service in 1941. McMillan describes the Australian-acquired version with care, detail and a certain second-hand love. Few, if any, reconnaissance flying boats of World War II could be described as attractive, but this amphibian aircraft, with its highly distinctive fuselage-positioned gun blisters, was particularly ugly. She weighed some twenty-two tons with a 104foot wingspan and was powered by a pair of 1200 horsepower Pratt and Whitney engines. Looks, however, were not important. McMillan describes the aircraft, quoting ex-aircrew, as a delight to fly. One of the many flights McMillan records in detail was an operation from Darwin to attack a target in Surabaya in the then Netherlands East Indies. The total flying time over water was twenty-one hours. McMillan skilfully conveys both the boredom and tension of such a long trip to the target, the danger while over it, and then the long flight back to landfall.

Australian-based Catalinas attacked many targets, including those on the Chinese coast, on Sumatra, Borneo and Java. Operations had their share of tragedy. From December 1941 to March 1943, seventeen Catalinas were lost with nine crews. The horror surrounding the loss of one aircraft that caught fire over the Solomon Sea can only be imagined. Another was lost in cyclonic conditions over the Timor Sea.

Perhaps it is easy now to forget how young these aircrew were: the captain of a Catalina crew might be just a little over twenty. One man recalls how he started training at the age of eighteen and was on operations by the time he was nineteen. Later he realised he had not experienced youth. It was largely the Depression generation that fought World War II; they sacrificed so much for a system that had given them so little. This book records the writer’s respect for them.

Peter Dornan takes us from the nine-man crew of the Catalina to the highspeed, single-seater fighter aircraft operating in the Middle East against Italian and German opponents. Andrew William Barr, known as Nicky, was born in New Zealand, but was raised in Victoria. His war biography as presented by Peter Dornan would not have surprised youthful readers of the Boys’ Own Paper. With what was an élite job as a wool classer and with a diploma in accountancy, he became a well-known international rugby player who was on a tour of England when war broke out. He joined the RAAF as a cadet, and qualified as a pilot officer in September 1940. His operational career did not begin until he joined No. 3 Squadron in November 1941.

Barr was the stereotypical fighter pilot. After some six weeks in action, he had destroyed five aircraft to become an ‘ace’. On 11 January he destroyed two more enemy aircraft and, in attempting to land and rescue a downed fellow pilot, was attacked by two Bf109s. One he destroyed, the other was claimed as a probable. He was then himself shot down. After five days of walking through the desert, he re-joined the squadron and was awarded an immediate DFC. He was to be shot down and to walk out on two more occasions. He had destroyed a total of twelve enemy aircraft.

Barr’s luck ran out in June 1942 when he was shot down and badly wounded. He spent five months in hospital in an Italian prisoner-of-war camp. After escaping from Italy he was recaptured, only to escape and be captured again. He was sent to a German camp. On the train, still in Italy, he again escaped. From there he joined up with irregular forces and organised an escape route for allied prisoners of war. While imprisoned, Barr was promoted to Squadron Leader, awarded a bar to his DFC. Later he was awarded a Military Cross for his gallantry on the ground.

Peter Dornan adds the colour, the detail, the excitement, the suffering and also the violence to this bare outline of Barr’s achievements. General Sherman once remarked: ‘War is cruelty and cannot be refined.’ This book, not for the squeamish, demonstrates this axiom only too well.

There are several factual errors, or at least matters for debate. One might be surprised to learn, for example, that the Bf109 was renamed the Me109 in 1938. Hitler did not annex Poland; he invaded it and occupied it. Six thousand Australian soldiers were not lost in Greece and Crete in April–May 1941. Still, those who read these books will not be concerned with such things. They will be rewarded, however, with a reconstruction of a past that hopefully will never be repeated.

Comments powered by CComment