- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Perpetual Fall

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Jordie Albiston’s latest collection opens with a remarkable poem about a woman falling from the Empire State Building and falling, at the same time, through the story of her life:

In the air, a moment can take on the time centuries span.

She falls through former selves above a thousand heads.

No one looks up. No one looks towards the bright sedan.

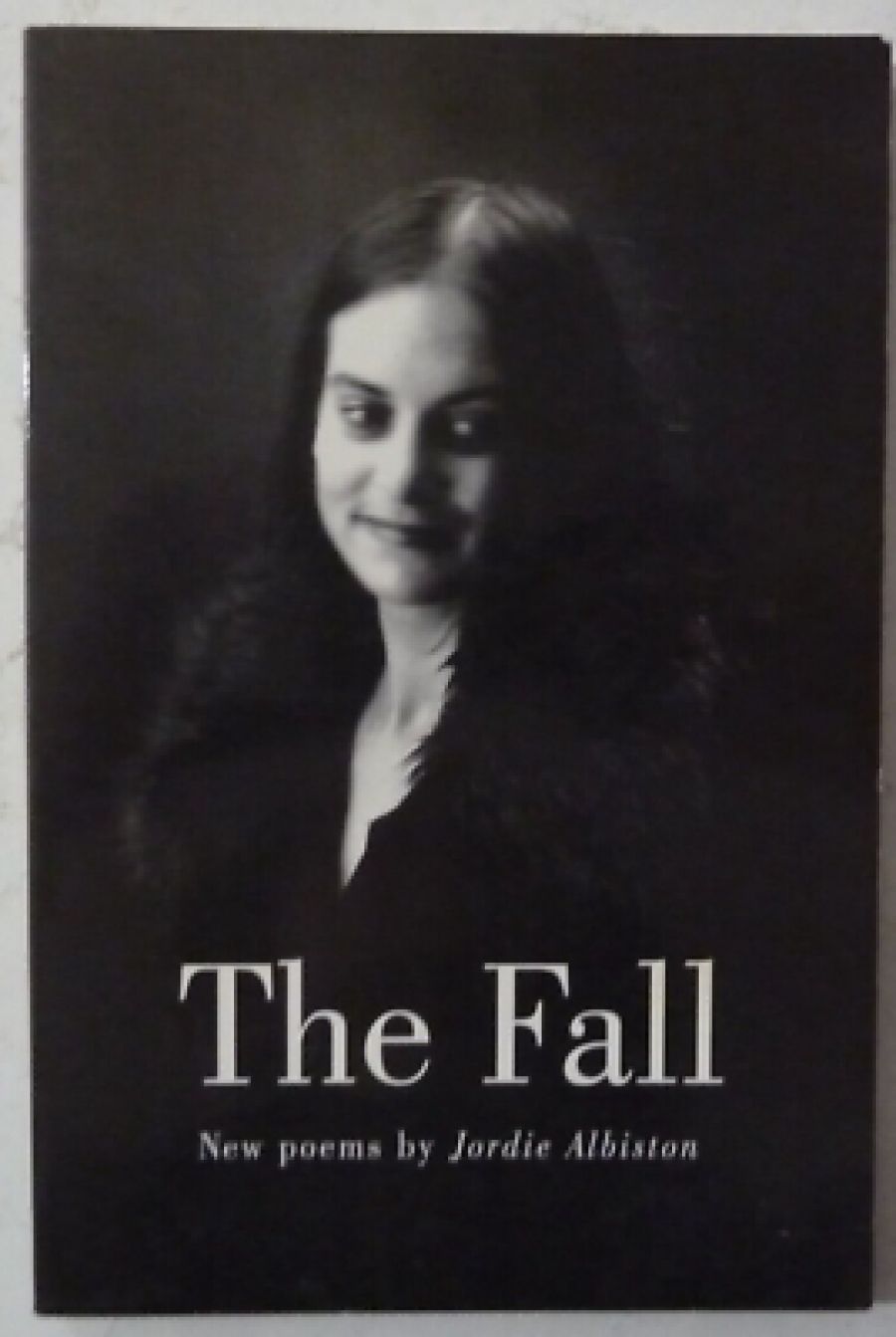

Within a handful of time, it will be her crumpled bed. - Book 1 Title: The Fall

- Book 1 Biblio: White Crane Press, $19.95 pb 86 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

She falls, self by self, over a crowd of a thousand heads.

Failing always at physics, this falling is her punishment.

In seconds, her body will lie in its metal bed

Where she shall sleep, no matter what the prophet meant

What this poem lacks in drama, it finds in suspense, albeit of a curious kind, derived from the discrepancy between its formal, almost stately, progress and the speed and violence of the woman’s fall. The poem addresses lucidly, even blandly, that impossible moment: a ‘handful of time’ that lasts twenty-two stanzas. And so, in its lucidity, this poem includes a sense of something strange: a stunned dissociation, a sense of time slowed down.

‘Failing always at physics, this falling is her punishment’: the poem works on this ineluctable logic of falling, which is really no logic at all, though it takes its force from the woman’s imminent death. And the poem treats this logic as something more than the death, as if this description of a suicide is really a poem about something else: its claim that ‘Moments are made to be flown through: you climb, and / If you have the courage, leap ... ’. For this poem, which ends with a death, concludes with a general statement about life: ‘To live / You must climb to the very top, for it is a very long fall.’

‘Kavishna’s account’ is another poem about a fall, the kind that serves as a recurring theme in this collection: a loss that doesn’t surprise anyone or stop anything:

Face down in a puddle

on Springvale Road is a

pretty far fall for a girl.I am Kavishna, I saw her

drown. I heard her call

into empty wet ground ...

With its wry sense of suburban tragedy, ‘Kavishna’s account’ sets the tone for a number of poems in this collection; poems about passing time with resort to daytime television, daily tasks and desperation: ‘Press on, through the delicate day of ritual reality: / the flags on the line, the forks in the drawer, the filial clichés / calling from coat hangers on the back of the laundry door.’

Some poems work in a more limited way, as witty, well-phrased exercises. ‘O Adjective’, for instance: ‘O Adjective, you would love this poem / but I will not employ you on principle. / You confused me with your two main functions … ’ But the strongest poems in this collection are striking. In ‘Dark Souls Swept Out Far Too Far for Saving’, Albiston uses rhyme patterns and patterns of assonance to make a strangely resonant word music:

Dark souls swept out far too far for saving

Weep salt tears that only salt seas know

For such souls there can be no safe haven.Listen, you can catch their distant ravings

Drift in to shore, when the northerly blows.

Those dark souls are out too far for saving …

This is a poem that reads like someone speaking in a dream. It is perhaps this quality of the perpetual that makes the ending somewhat dissatisfying: ‘In the sea, their images are graven / Upon the black heart’s mighty undertow: / May such souls swept out too far for saving / Find love, find love, in their sailors’ heaven.’

Again, in other poems in this collection, Albiston treats love as something understood. ‘Chained Letter’, for instance, is an uncharacteristically loose poem:

... So, I’ve decided, today

Is the day to be more true

In my love for you:

To be a wife not only on paper

And to mean more than mere words

Can say. I give you my word

That I’ll forget about me ...

This is a looseness that measures, perhaps, how far Albiston’s formal control extends the range of her other poems, for the ‘Wye River’ series of love poems are some of the most pleasing in this collection.

The series consists of daily poems. In each one, Albiston takes up the same images from the landscape. So, in ‘IV. On the Rocks, Wednesday,’ she writes: ‘I plotted a track between blue and / white and thought This is like love: you /choose a direction and walk it, searching / for ritual, side-stepping rips, reefs, rocks.’ And in ‘V. From the Verandah, Thursday’, she revives the image: ‘I try to traverse the colours of our love: / the blue and the white which keep me by /you, the shade that sends me away.’ In this way she makes an imaginative landscape for love, as it were. And if that love seems sometimes a little too ‘poetic’, it is all the same poetry, with such gentle cadences and grace notes.

Comments powered by CComment