- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Clive James is a fussy A-grade mechanic of the English language, always on the lookout for grammatical misfires or sloppiness of phrasing that escape detection on publishing production lines. Us/we crashtest dummies of the written word, who drive by computer, with squiggly red and green underlinings ...

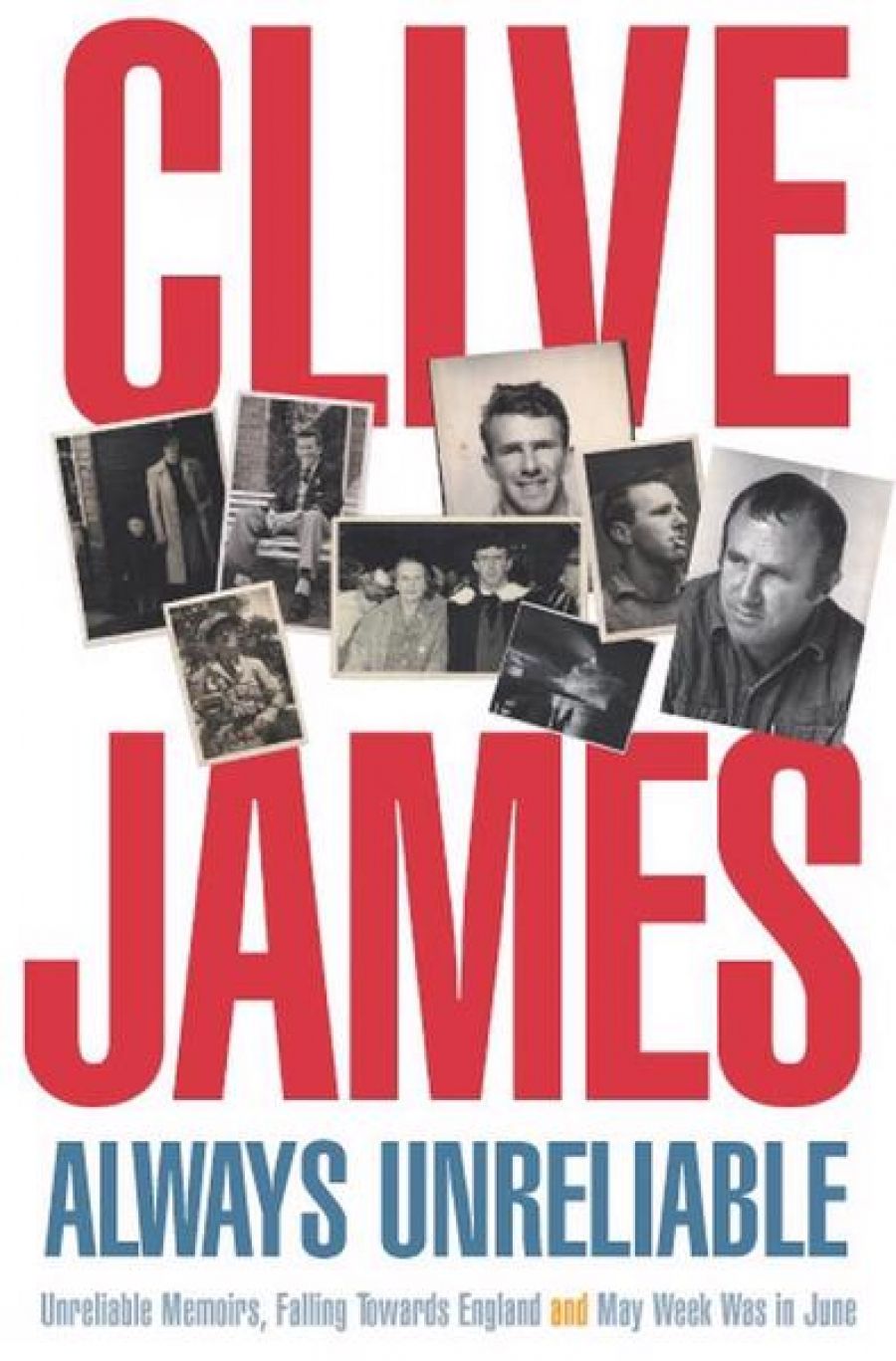

- Book 1 Title: Always Unreliable: The memoirs

- Book 1 Biblio: Picador, $30 pb, 537 pp, 0 330 48875 9

A plain and welcoming conversational style underlies the prose in Always Unreliable, at least initially. His writing gathers a smart, even dandyish momentum as it goes along. James’s verbal felicity appears to be in exact proportion to the degree of education he describes. This book is about getting an education or, rather, discovering literature, languages, music and art. It contains little drama to speak of, and not much suspense, apart from the drama of waiting for exam results, trying to write a great poem, or deciding whether Georg Solti was a good or bad conductor of Wagner. This book is about the growth of a mind, a very fine mind, and the growth of its owner’s confidence to display it, which in turn spawns the budding of his multi-career career.

By the end of Part One, the childhood section of the book, which James wrote as a grown and graduated man, we are not surprised to be told that he has discovered F. Scott Fitzgerald, the supreme ‘I’ writer of fiction, and master of adroitly linking story details and the movement of time in a couple of brisk sentences. James himself is sweeping us through his life with a light, but not careless, touch. Two pages before this revelation, James tells us that he is ‘falling upwards from the past’ on learning of the death of a friend. ‘It was all going away from me. I could feel a vacuum plucking at the back of my shirt.’ Very Fitzgerald.

In Part Two, James has emigrated to England to take up job after dead-end job and endure a peripatetic few years going from one eccentric landlord to another. In the third, he has secured a place at Cambridge, studying the English tripos, whatever that is, and making a life out of using his brain as a film and book critic, as well as director of the famed Footlights Revue, rubbing talents with the likes of Eric Idle, John Cleese and Julie Covington.

James’s paragraphs become more essay-like and namedroppy in their learning, dense with recollections of university life, and possessing a worn-in sophistication of tone. By now he is set on the path to fully developed, confident opinion-giver and opinion-setter, not to mention poet, publishing in most of the arts rags that mattered in the United Kingdom. He can tell you about Swift, Shelley and Dickens. He can tell you about Kurosawa, Fellini, W.C. Fields, Dante, and Donatello. He can apply his genius for mocking portraits to any pompous target – dotty Cambridge dons, for instance. Indeed, Always Unreliable includes a brilliant passage (just a few paragraphs) sketching F.R. Leavis in bitter old age, when, in James’s words, the great literary critic’s views had become ‘dogma distilled into a pathogen’.

James can also disappear up his own you-know-where with offerings such as, ‘Only last year, catching Raymond Aron’s enthusiasm for Montesquieu, I devoured the Lois as if it were The Lady in the Lake.’ Huh? And a sentence such as, ‘For someone of my temperament, going over the top is a necessary step towards coming to terms’, dangling out there as it does on page 488 without any more information, is too obscure a personal statement, even for a memoir.

If you want one-liners – and that’s logical enough, James is one of the best gag-makers of his generation – Always Unreliable has its share, though for mine, the book’s jaunty, detailed anecdotes provide the belly laughs. In fact, a few of the one-liners he attempts here, such as the one about throwing a frisbee – ‘It headed for the Cam like Hitler for the Rhine’ – are cringingly below the standard you get in his ‘Postcard’ series and published after-dinner speeches.

James has language and quality opinions to match any subject or occasion. The same man who Hitlerised a frisbee can produce a donnishly-put insight of this high calibre: ‘[G.B.] Shaw’s failure of imagination with regard to Stalin [is] clear evidence that the creative mentality should guard itself against its own inevitable pretensions to omniscience.’

Clive James has spread himself thickly across many fields of interest and occupation, as if easily bored or not easily hard-pressed. He is, of course, an international television celebrity, a rare example of that breed: he looks like your local roof-tiler rather than someone conceived in a cosmetic kit. Even on television, clever words were, and still are, his act, his hook. God knows what he would have done had he not gone to England but stayed at home to ply his wares. Where would they have slotted him? What would he have done? Become an academic? Too widely read for that. A journalist? Too deeply read. Writing television skits? For Graham Kennedy if he was lucky – Ernie Sigley if he wasn’t.

Comments powered by CComment