- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Architecture

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Private Murcutt

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Holidaying in Tuscany, I once met an escapee from a Glenn Murcutt lecture. The class of American students had flown from New York to be immersed, in the modern manner, in six weeks of architecture beside an Italian beach. Murcutt delivered the first lecture.

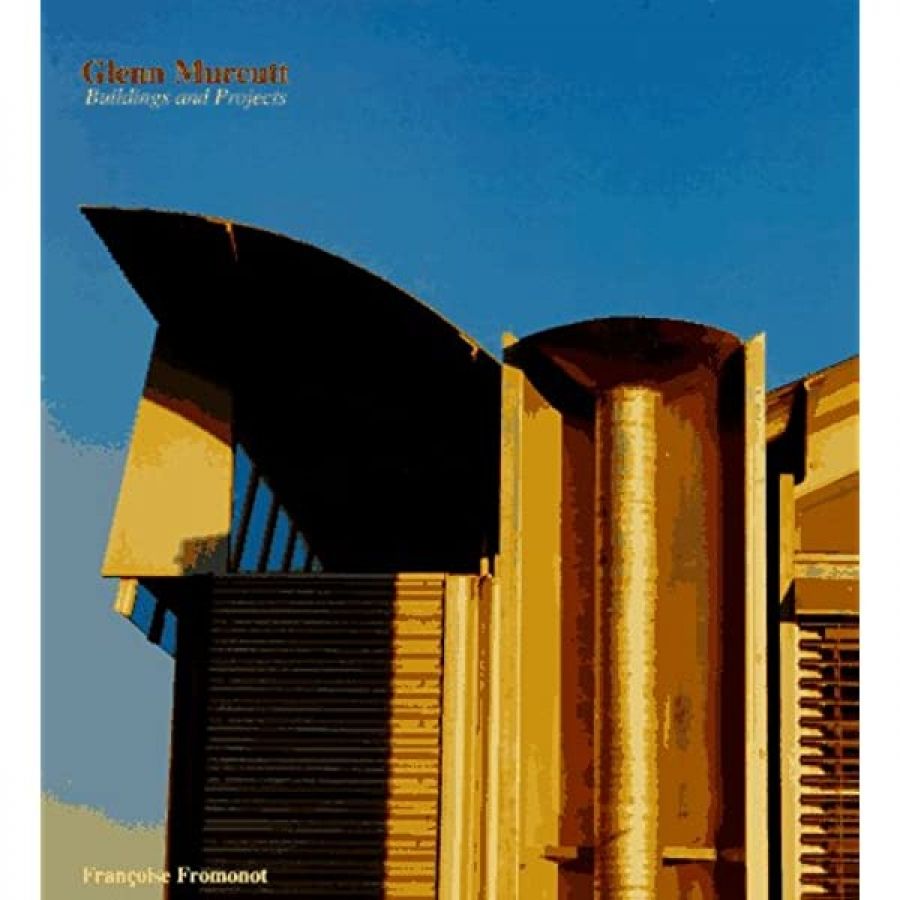

- Book 1 Title: Glenn Murcutt

- Book 1 Subtitle: Buildings + projects 1962-2003

- Book 1 Biblio: Thames and Hudson, $120 hb, 325 pp

Buildings + projects 1962–2003 is an updated version of the author’s Glenn Murcutt: Works & projects (1995). It adds ten new buildings and projects to the twenty-three selected for the first book. And it is a beautiful production: the typeface is clear and the photography remarkable. Each page is a delight. The text relates exactly to the photographs and drawings, so there is no confusion about the relationship of description to illustration. While these may seem to be essential components, and not worthy of comment, that is far from the case with books on architecture. Confusion often reigns, to the detriment of clarity. I find it extraordinary that the book designer wasn’t credited, nor any of the photographers.

Fromonot says that Murcutt was somewhat surprised when she turned up in Sydney in 1991 with a research grant from the French foreign office to write her first book on his work. One can understand why. Having once pursued the notion of funding from our Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade for an exhibition of the work of Australian architects at the Venice Biennale, only to be told that the limit of assistance would be a function at the embassy, I share Murcutt’s amazement at the French imagination.

In her introduction, Fromonot notes, with splendid honesty, that she hopes the book’s acuteness has not been blunted by her admiration for Murcutt. Well, as I see it, it has. Time and again, mundane statements are not challenged or developed as arguments but simply repeated as though words from the master stand as obvious truths. There is also an innocence in her understanding of the practice of architecture. Here is an example:

Murcutt has never thought of drawings as a pretext to producing works of art; he thinks of them more like a master builder … a graphic technique whereby a building may be conceived in terms of construction, intended to clarify complexity and avoid fudge.

I am uncertain what other types of working drawings could exist. If a construction drawing doesn’t clearly indicate how the building is to be constructed, then it fails in its purpose. To present this daily aspect of architectural practice as something unique is absurd; it implies that most other architects are fiddling around producing fudgy works of art all day. If only.

At various points throughout the book, Fromonot emphasises Murcutt’s well-publicised practice of subjecting his clients to several years of waiting before they get to the top of the client queue. It’s a clever marketing ploy but possibly quite trying:

Potential clients have long had to take their place in a three to five year waiting list before he can fit them into his schedule. Not that the waiting time is wasted: ‘My clients have to work hard,’ says Murcutt. In the course of regular, informal meetings they have to specify their habits and way of life, then work out their brief with the architect, even if that means adjusting their initial aspirations, so that everyone agrees on the basic aims of the scheme.

Am I being touchy here, or does this mean, as I think it does, that if a client’s habits and way of life and aspirations don’t coincide with the architect’s, they need to have a bit of a rethink? Architects working in the residential area are generally assumed to offer art and expertise to meet the client’s brief, not to tell the poor devils how to live.

But that is not all.

Murcutt has managed to imbue most of his clients with a sense of responsibility for the wider ecological issues implicit in all building work. Sometimes he has even encouraged them to contribute to his own critical thought processes by offering him an opportunity to develop his ideas further, on their behalf.

Does this mean that Murcutt allows his clients to let him build for them? Or is it just Derrida-speak?

Murcutt has made a minimal architectural contribution to the public domain in Australia. Fromonot suggests that this is because local councils have, on occasion, knocked back his projects. This is an area deserving of more discussion than the author has given it, because this avoidance of a commitment to an architecture of wider import than the private commission for the single house will surely, in time, undermine Murcutt’s relevance to the story of Australian architecture.

Public architecture is a tough process: developing a response to the brief, which is built on an intense understanding of the requirements, histories, and cultures impacting on the commission, and then working with numerous levels of bureaucracy to achieve a commitment to proceed, are just the beginning. Gaining and holding the funding – often across changed administrations – and bringing the project to completion through the building process can take years. It’s not about throwing in the towel when a permit’s refused.

Part of Murcutt’s reluctance to move his work from the single house in the sublime setting must be due to his abhorrence of both city and suburb. On these issues, Fromonot acknowledges that the vehemence of his statements sometimes verges on anathema:

To him, the dense metropolis is a model now incapable of providing a response to urban growth commensurate with the higher necessities of preserving the planet. The way he sees it, concentration stimulates consumption and increases pollution, while the over-regulated lives led by individuals in agglomerations are debased by being cut off from nature.

Fromonot points out how Murcutt scoffs at suburbia: ‘We think we are getting all the benefits of the city, and like all compromises, we end up with [neither] one nor the other, let alone both.’ To avoid both city and suburb is a refusal to engage with ordinary lives. Murcutt seems to have no fondness for the human race. He has bypassed the opportunity offered him in this book to develop an argument for how humanity should inhabit the planet.

The book is a visual joy. The photographs are excellent and are accompanied by plans, sometimes sections and details, and project descriptions. The project information is clear and beautifully laid out. It’s just that the portrait of the artist is less than endearing.

Comments powered by CComment