- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Entering the maze

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

We expect memoirs to be true – it is one of the main reasons we read them – but we have also grown accustomed over the years to the idea that, while the memoir may be true in spirit, events may not have happened exactly as described. Indeed, it is not unusual for the memoirist to include some prefatory remarks to that effect. Such caveats seem fair; we have come to see them as no more than acknowledgments of the way things are.

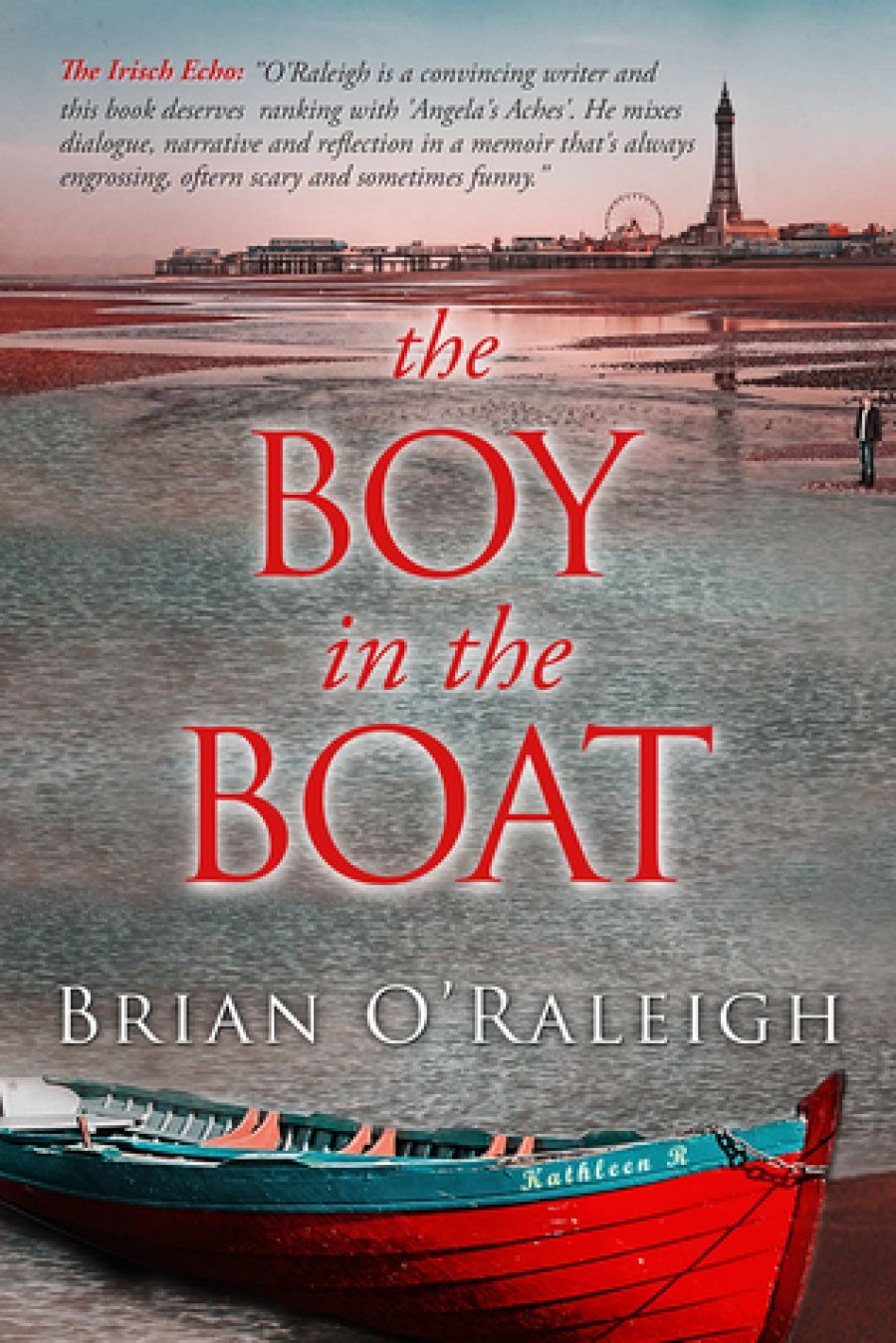

- Book 1 Title: The Boy in the Boat

- Book 1 Subtitle: A memoir

- Book 1 Biblio: Limelight Press, $34.95 pb, 493 pp

- Book 2 Title: A Story Dreamt Long Ago

- Book 2 Subtitle: A memoir

- Book 2 Biblio: Bantam, $29.95 pb, 299 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

More or less, although ‘fictional names and descriptive elements have sometimes been used’. It is not quite clear what this means, or exactly where in the text fact elides into fiction, but there are places, such as the description of a short-lived tryst in a French chateau with Gabrielle in which they ‘make love in a bed by a fire, shadows dancing on a wall’, where the language of a certain kind of fiction does seem to have taken over. For the most part, however, the shadows are much less romantic, embodied in self-lacerating accounts of bad behaviour, touched as such accounts often are by an underlying pride in just how bad that behaviour really was. The problem with stories of addiction and drunken excess is that they are inherently tedious and repetitive, and it takes a writer of real distinction to overcome that disabling fact. The cycle of drinking and violence and failed relationships in The Boy in the Boat seems to go on and on, until at last some form of redemption is in sight.

‘Address your shadow,’ advises one of the many therapists and self-professed gurus to whom O’Raleigh eventually turns. Another suggests helpfully that tears ‘can open the way to the truth’. These enigmatic phrases and others like them provide him with a framework, a way of shaping life and giving it meaning, of making it true or at any rate significant. This framework is an odd collection of New Age ideas and pop psychology and Balinese funeral rites, and it reads like something imposed, out of desperation, on the messiness of life. On the other hand, it seems to have worked for him: he now runs workshops and seminars, ‘in the area of personal growth and development’.

For Phyllis McDuff, in A Story Dreamt Long Ago, the ‘truth’, which she is careful to place in inverted commas, ‘is evasive’, and those who seek it ‘are destined to suffer many disappointments’. She offers, instead, the story of her own search for the truth about her mother, with all its frustrations and false leads, rather than anything approaching a complete picture. ‘I can only share my journey,’ she tells us, ‘offering the fragile threads that lead towards Bettina.’ The truth, in other words, is coloured by her perceptions. McDuff goes in search of the facts about her mother, but is repeatedly frustrated by the contradictions she discovers, and by the trails that go cold. In searching for the truth, she tells us, ‘we enter the maze’.

From a life of privilege in pre-war Austria, Bettina Mendl, driven from Vienna by the Nazis, arrives in Sydney in 1939. Fearful of possible internment, she goes bush, marries Joe, an Irish-Australian, and has two daughters. After the war, she is drawn back to Vienna to claim her inheritance, and so begins a see-saw over many decades of repeated journeys back and forth, sometimes taking her family with her, sometimes not. It is an unusual life in its detail – ‘a curious blend of European aristocratic privilege and outback Australian deprivation and austerity’, as McDuff states – but, in another sense, typically Australian, as it attempts to reconcile irreconcilable experiences and values: the old world and the new.

At the core of the book are two drawings, possibly by Picasso, given to McDuff by her mother. Are they genuine? She embarks on an on-again, off-again search for their provenance, but never obtains a satisfactory answer, just as her mother’s real background and character elude her. McDuff describes lives – her mother’s and her own – in which people cross their paths and then just disappear. I never saw them again, she frequently says, as if expressing impatience with any idea of life in which things come full circle and a satisfying pattern emerges. That is the stuff of fiction, a genre that McDuff finds uncongenial. She studies German at university, but does not enjoy it. ‘Kafka turned my stomach,’ she says in an unusually strong turn of phrase. She is equally tough on Shakespeare, and the ‘interminable analysis’ of his ‘techniques’.

There is something refreshing in all this, in the determination to tell it as it was and as she sees it now, without tying things up too neatly. Unfortunately, her nerve fails. Her beloved father dies when she is away at school, becoming one of the many people she will never see again, but McDuff cannot leave it at that. She describes a return visit, much later in life, to the farm where she grew up, where her children and their cousins play happily ‘on the exact spot where he had fallen in his fatal accident’. She has told these children little of her past, or of her father. In due course, the children send an emissary into the house to collect refreshments. ‘I asked was everything all right out there in the shed. Were they happy playing all alone? “Oh,” says the five-year-old, “we’re not alone. Joe’s out there looking after us.”’ The impulse to impose some kind of order and continuity is too great. It takes the form of a ghost, and the price is credibility.

Comments powered by CComment