- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Survival stories

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Eva Marks was nine years old and living in Vienna when Kristallnacht forced her family to leave Austria. Although her parents separated early, there was no shortage of money during her first nine years. Her mother ran a successful business manufacturing exquisite accessories for fashionable women, which involved occasional travel. At these times, Eva was left in the care of her grandmother and her two aunts, who were as independent and strong-willed as her mother. An only child, only niece and only grandchild, she was greatly indulged, although conscious that she lacked siblings and happy parents.

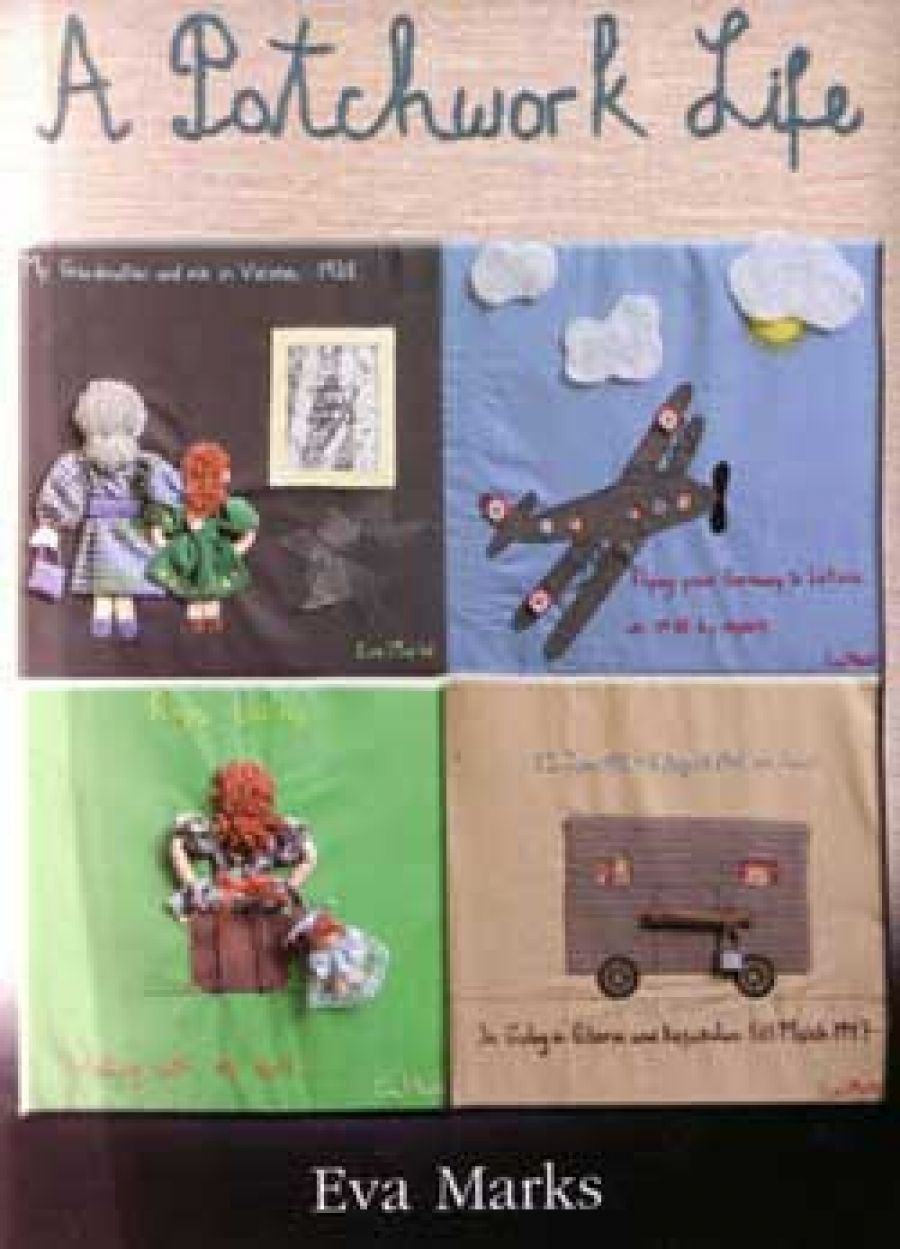

- Book 1 Title: A Patchwork Life

- Book 1 Biblio: Makor Jewish Community Library, $25 pb, 228 pp

- Book 2 Title: Point of Departure

- Book 2 Biblio: New Holland, $24.95 pb, 304 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

In the terrible winters of Kazakhastan, each barracks was given only a small bottle of kerosene and a cotton wick for lighting each week. A series of grim details stay in the mind long after reading: Eva’s near drowning in the camp’s cesspit; her operation for appendicitis without anaesthetic; and the prisoners’ struggles with eagles while hunting the same prey of rats as they worked in the fields. Other incidents highlight the frequent reversal of parent-child roles as Eva draws on energy lost to the adults, as well as illustrating the extraordinary resourcefulness, initiative, and life-force that upheld her both in the gulags and later. A spare narrative in terms of style, and all the more telling for that reason, A Patchwork Life is also underpinned by the author’s mature reflections on her experiences and the world’s postwar response to them. Amazed that Hitler’s crimes receive so much more attention and acrimony than Stalin’s, she endorses another writer’s comment that popular memories have coloured our perception of modern Germany but that it is our absence of popular memory that has coloured our perception of modern Russia.

Eva’s family’s release did not eventuate until February 1947, and even then it was brought about by the prisoners themselves, who went on a hunger strike. They returned to Vienna as they had come, zig-zagging slowly through Russia in freezing cattle trucks for six weeks. If the reality of what she and others endured continues to amaze the author, so do certain postwar encounters which signalled that she was expected to bury the experiences as a matter of good form.

Eva’s story continues to the present, tracing her reactions to postwar Vienna while living with her grandmother and mother, now married to a domineering Austrian, her departure for Australia when she was seventeen to be reunited temporarily with her father, her resourceful struggles for survival in this country, her marriage to Stan Marks, journalist and author, and their life together in Britain, Canada, the US and, finally, Australia. Later tragedies scar her story, but nothing can dent her will to survive and to meet whatever challenge is thrown in her path. An inspiring autobiography, despite its horrors, this is a book that deserves to endure.

Pamela Hardy’s Point of Departure might be described as a contemporary story of survival and discovery of the self through challenging and difficult circumstances. Frustrated by a failed marriage and the lack of opportunities common to her generation, the author, in her fifties, apparently decided to test her independence by backpacking around the world for a year. Her journey takes her to the US, Canada, Denmark, Norway, Finland, Sweden, India, Greece, Egypt, Turkey, Zimbabwe and South Africa.

Hardy’s descriptions of these places rarely rise above the clichés of travel guides: New York is a ‘vibrant metropolis’ and, at the Niagara Falls, the ‘enormous volume of water plummeting into the gorge was a beautiful green and seethed with white froth’. Her accounts of backpacker hostels, on the other hand, are packed with gritty, graphic detail, extending to descriptions of toilets and the irritating personal habits of other backpackers. The narrative picks up in the section on India, when her bag is stolen with near disastrous consequences. This section incidentally illustrates, for this reviewer at least, the fact that some people in Third World countries still experience conditions that are barely better than those in the Soviet gulags of the 1940s.

Comments powered by CComment