- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A young artificer

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In the penultimate chapter, Bernard Smith describes a meeting of the Sydney Teachers College Art Club, an institution he founded and later transformed into the leftist NSW Teachers Federation Art Society. The group was addressed in 1938 by Julian Ashton, then aged eighty-seven and very much the grand old man of Sydney painting and art education. He spoke at great length on the inadequacy of the NSW Education Department’s art teaching practices. Smith adds that Ashton also ‘told his life story (as old men will)’.

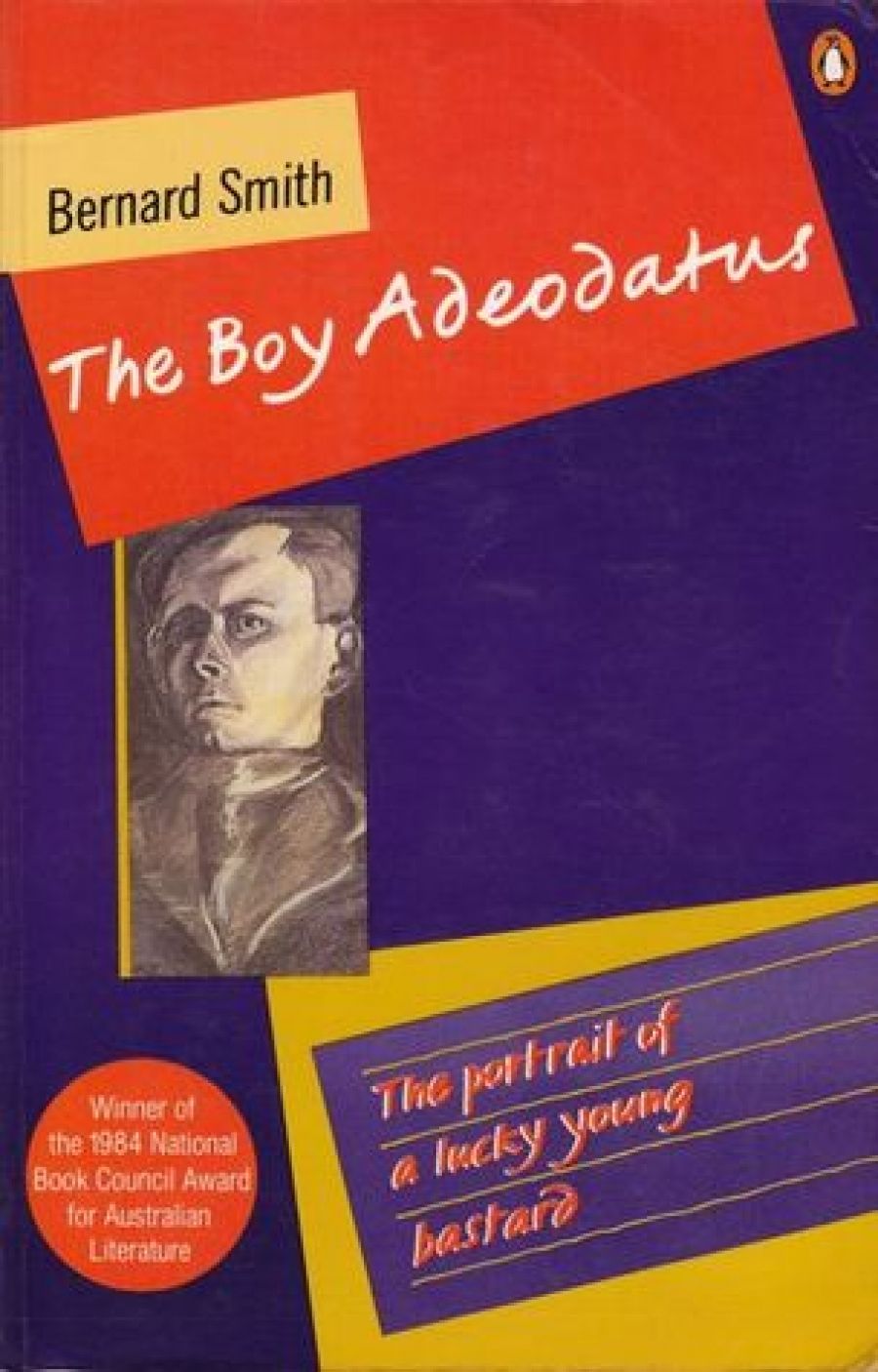

- Book 1 Title: The Boy Adeodatus

- Book 1 Subtitle: The portrait of a lucky young bastard

- Book 1 Biblio: UQP, $26.95 pb, 302 pp

One event which closes the book is Smith’s immersion in the cultural wing of the Australian Communist Party. He joined the party in 1939 or 1940 (the dating isn’t clear) and remained a member for four years. Another event which helps to round off the book, and is much anticipated, is the loss of his virginity. Yet another is his decision, after some years seriously pursuing it, to abandon painting for the vocation of the art educator.

We are not told whether Smith later resumed painting or regretted his decision. It should be said that this is not a rueful autobiography of a painter manqué, but an indictment of a culture manqué. Nor are we told how Smith now regards his career as a teacher devoted to building a sophisticated knowledge and appreciation of art in Australia.

A less ambitious, more conventional autobiography might have answered or broached my literal-minded questions. Smith distances himself, I think overdistances himself, from conventional personal memoirs. The Boy Adeodatus is something like an historical fiction, in fact, told in the third person by a magisterial, cunning narrator.

As a contribution to that rich Australian genre, the part-biography of an intellectual, artistic, literary, or otherwise ultra-sensitive young man, this book is powerful but eccentric. Fortunately, it is unlike so many examples of the genre which see childhood in idyllic, pre-Freudian, innocent terms. It is the fusion of otherwise mundane materials with a metaphysical conceit which makes this book both charming and maddeningly confusing for the reader.

At another level, much of this book is a remarkable contribution to the social history of intellectual Communism in Australia in Smith’s given period. He was one of a small band of artists and art connoisseurs who joined the party at a most unpropitious time, during the ‘phoney war’, in advance of the much larger movement by young intellectuals into the party during the wartime and post-war years. The book is equally valuable as a contribution to the social history of childhood, or childhoods in Australia; Smith was indeed a ‘lucky young bastard’, since he was not adopted in the manner which deprives a child of knowing his actual parents, or even knowing the fact of his illegitimacy. He spent the first nine months of his life with his mother, and remained in contact with her after he was fostered or ‘boarded out’ with a remarkable family in the Sydney suburb of Burwood (then an outer suburb). The third-person narrative gives Smith great freedom to detail the predictable and unpredictable relationships between ‘the personal and the political’. As the book proceeds towards the crucial decisions which conclude the subject’s childhood, Ben/Bernie becomes increasingly a didactic plaything of social and historical forces. There are perhaps too many authorial interventions of this kind: ‘Events on all sides were conspiring to radicalise his views.’ At times one suspects that too much retrospective knowledge is imposed on certain childhood incidents or turning points.

The problem of the narrator’s intentions really becomes acute as one tries to understand the point of the analogy between Ben/Bernie and the boy Adeodatus, the illegitimate, precocious, and beloved son of St Augustine, who died young, at the age of seventeen. The key relationship in the text is between Bernard and his actual mother; his actual father, Charlie Smith, took little interest in him and was far from saintly. One possible reading is that Ben/Bernie spiritually died when he failed to ‘return’ altogether to the Catholic Church, and eventually embraced Communism. It could also be that conversion to Communism was a kind of spiritual death, but in this case the point of the analogy lies beyond the time span of this book.

Smith’s habit of inserting frequent quotations, mostly from St Augustine’s Confessions, into the text, in italics, also complicates the matter, suggesting an identification with St Augustine himself. It may be that readers more familiar with allegory, or even with allegorical painting of the kind which the young Bernard Smith executed and then abandoned, will find the Augustinian conceit in this text more plausible or more meaningful than I did. While I found the book gripping, a profound work of autobiographical art, it is also a work of overweening artifice.

Comments powered by CComment