- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Bounty from zero

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

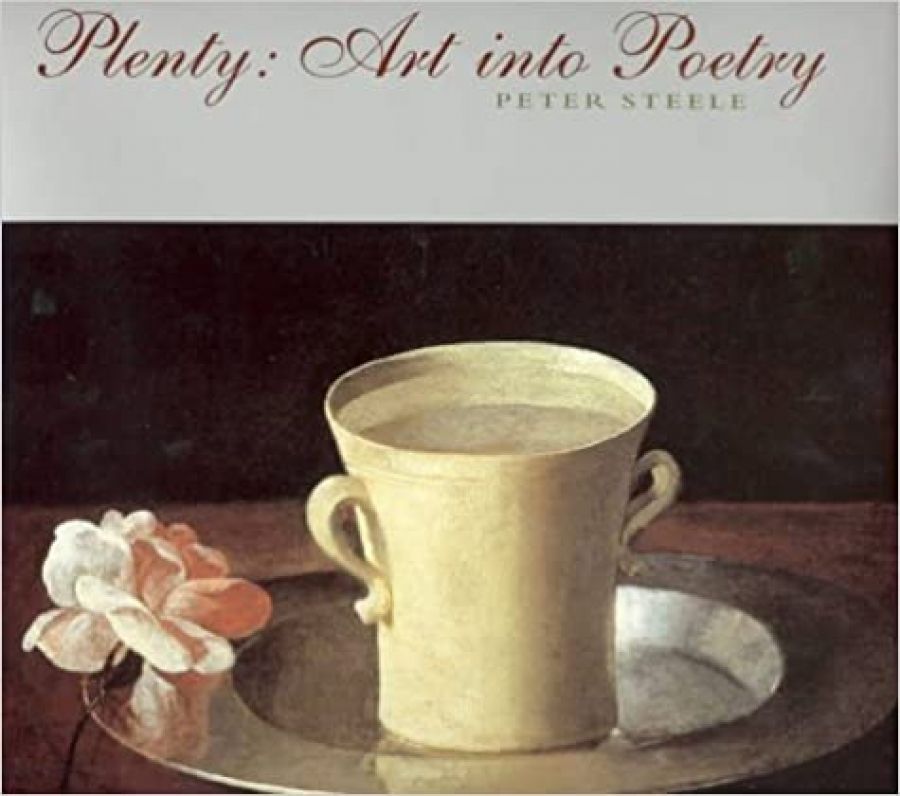

Here is a production that most poets would die for. Peter Steele’s new book is a spectacular hybrid beast, a Dantesque griffin in glorious array: it is a new volume of poetry and an art book, with superb reproductions of works of art spanning several centuries, from collections all over the world. Paintings most of them, but also statues, sculptures, objets d’art, a toilet service, the figured neck of a hurdy-gurdy, a hoard of Viking silver and a diminutive six-seater bicycle. And the reason for this pairing is that these are all ekphrastic poems, ‘poetry which describes or evokes works of art’, as Patrick McCaughey glosses it in his introduction. How Steele brought off such an ambitious venture I can’t imagine.

- Book 1 Title: Plenty

- Book 1 Subtitle: Art into poetry

- Book 1 Biblio: Macmillan Art Publishing, $77 hb, 128 pp

Plenty indeed: one of the impressions the book makes is of the gratuitous abundance of art, this product of the imagination that might not exist but does. One of the poems says as much, ‘bounty from zero, that cannot be and is’; Steele is speaking of the pieces of fruit in Sánchez Cotán’s Quince, cabbage, melon, cucumber, but the same might be said of the cosmos. Steele’s concluding essay also speaks of ‘what need not have been but is’. The book is, trebly, a conversation between the imagination and the world, first in the various artists’ representations and then in Steele’s re-viewings through the lens of their art, as well as that of his own imagination. Appropriately, McCaughey quotes Wallace Stevens: ‘The world about us would be desolate except for the world within us.’ Yes, and vice versa. But Stevens also said, ‘The eye sees less than the tongue says’, so let’s turn to the poems.

There is a risk, in such a book, that the reader might become simply a viewer. Fortunately, there is little danger of that here, because Steele is such an arresting poet. His poems shine with wit and intelligence, with love of the ten thousand things of the world, with compassion, with a deep knowledge of, and engagement with, art. And, of course, with a gift for words and their secret lives: ‘a falcon … / rocked at peace on a wrist and biding its time’; ‘oceans folded briefly home as a moon / whistles them in’; ‘the forest uneasy beneath the unusual wind’ (both humorous and ominous); ‘his wide mouth practised about her name’ (Christ to Mary Magdalene). The poems abound (plenty again) with such charged surprises. Inevitably, some are more dependent than others on their accompanying art for immediate impact. Since their future life will be in a humbler context, bereft of their begetting images, how will the reader fare without the facing picture, particularly in cases where the work of art is little known? I found myself placing the poems into one of three categories: those that seemed dependent on the image (‘A Resurrection’, perhaps, based on Rosselli’s illuminated parchment); those that stood in a finely judged balance between indebtedness and separate existence; and those that were ‘derivate not dependant’, as Steele said in another context. In the second group, and one of my favourites, is ‘An Angel from the Bombardier’, based on a bronze angel by the cannon maker Jean Barbet (perhaps his sole work of art). Here, the poem tells us all we need to know and reproduces the quiet eloquence of the statue:

… this limb of compassion, marred

as we have him now with pitting flaws

at chin and feather, but caught still by a vision

of peace untrammelled …

‘April 25’, a fine poem obviously about Gallipoli, is in the third group. While George Lambert’s Anzac, the Landing 1915 may have prompted the poem, it is not necessary to its reading. Rather, they could be seen as collateral descendants of the same event. There is humour, too, throughout: see ‘Tandem’, which accompanies that bicycle and gives a nod to Gwen Harwood.

Steele’s choice for the cover, and indeed the title poem, would have been my own – Zurbarán’s A cup of water and a rose on a silver plate, chastely ravishing and inexhaustible in its simplicity: ‘our planet’s road silvered about its heart, / petals and water naming plenty’, as the poem concludes. Simple things which bear the imprint of our looking and holding, our longing to stay in this world, which, in the words of Lawrence Durrell’s Balthazar, ‘represents the promise of a unique happiness which we are not well enough equipped to grasp’. Art gives us both the promise fulfilled and the promise ungrasped, and so do these poems.

Comments powered by CComment