- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

From at least the mid-1980s, it has been almost obligatory for Australian reviewers to bemoan the dearth of contemporary political novels in this country. In some ways, this is a predictable backlash against the flowering of postmodern fabulist novels of ‘beautiful lies’ (by such writers as Peter Carey, Elizabeth Jolley, and Brian Castro) in the past two decades ...

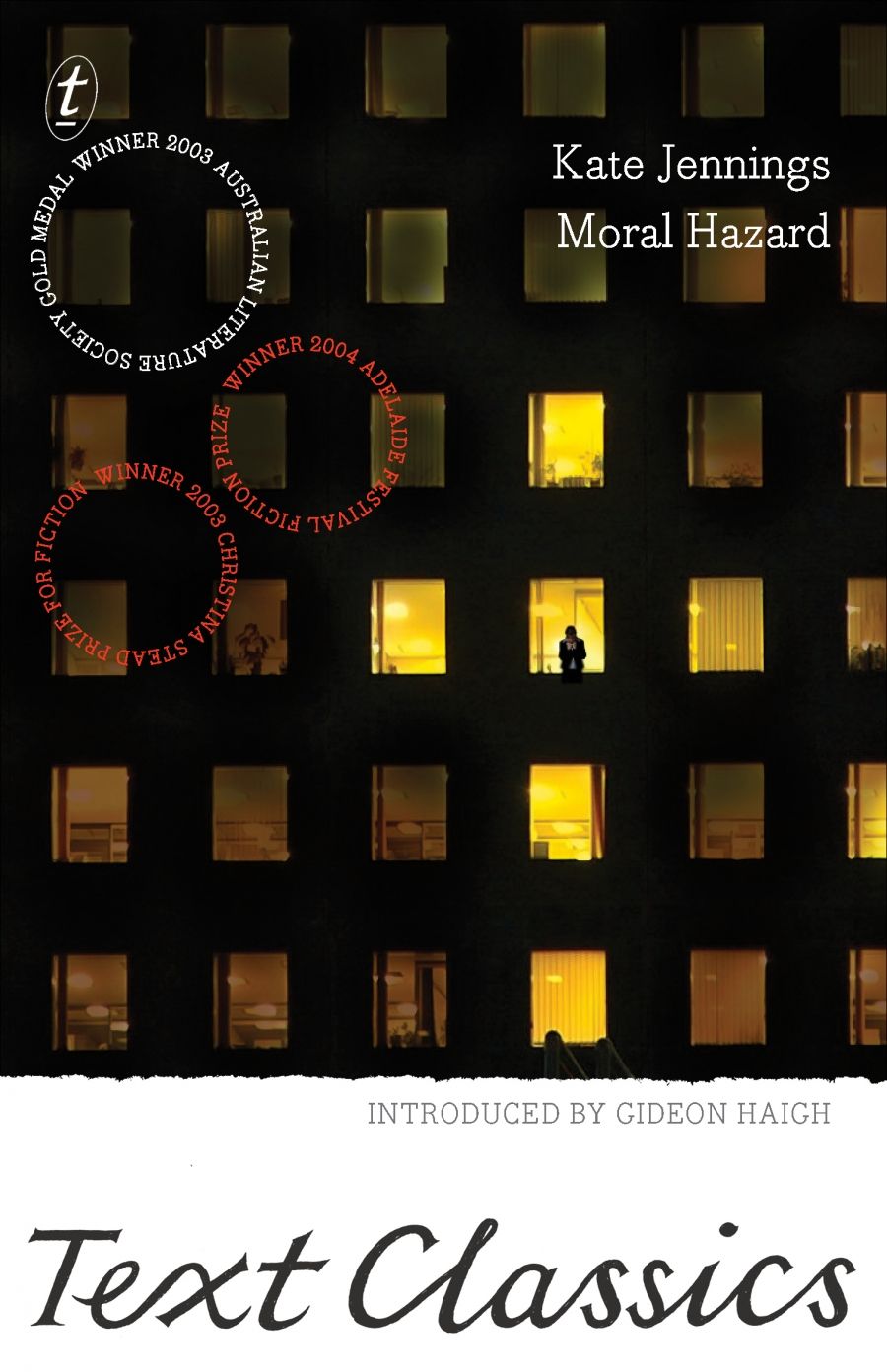

- Book 1 Title: Moral Hazard

- Book 1 Biblio: Picador, $28 hb, 175 pp, 0 330 36340 9

- Book 2 Title: Judgement Rock

- Book 2 Biblio: Penguin, $22 pb, 201 pp, 0 14 025429 3

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): images/ABR_Digitising_2019/August_2019/9780140254297.jpg

Yet, ironically, as the political realities of life in this country have become more complex, the critical sense of what constitutes the political seems to have become narrower. Forget 1970s notions of the personal being the political. When critics invoke the great white whale of the political novel these days, they usually mean a book that will directly address the capital-P Politics of the party room, hard economics, or perhaps, at a stretch, the boardrooms of the nation. Yet, while the critics continue to sit in their crow’s nests scanning the horizon, many books with a more complex and layered sense of the political have passed under their radar: some of the novels dismissed summarily as ‘grunge’, for example. For my money, Christos Tsiolkas’s Loaded was one of the more interesting political novels of the last decade, finding a reflection of the corruption of ideals at a governmental level in the disengagement of its young hero; it also recognised that, in a global world in which culture and consumerism and politics are so often intertwined, simple political divisions between Right and Left (let alone a sense of sexual or racial identity) are increasingly fraught. Perhaps realism is not even the most appropriate mode for reflecting the political complications of the present. I greatly admired the way that Kim Scott used the techniques of South American magical realism in Benang to find an overview of the sad and complicated history of race confronting us in this country.

I suspect it is the case that Australia has had complex varieties of the political novel for years. It is up to critics – particularly in this age of market-driven literary culture, so often reduced to soundbites and personalities – to take responsibility for widening the idea of the political and not look about nostalgically for the simpler novels of yesteryear.

These thoughts buzzed about in my head as I read Kate Jennings’s new novel, Moral Hazard. Jennings has combined the most boysily political of subjects – economics – with the most personal of narratives – the illness and death of a partner – producing a strange, sharp, original book.

When her much older husband, Bailey, is diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s, Cath, an expatriate Australian writer living in New York, is faced with both a financial and personal crisis; she has to find well-paid work to finance his care. After canvassing their acquaintances, she finds a lucrative position as an executive financial speechwriter for Niedecker Benecke on Wall Street. This is odd work for a forty-something ‘bedrock feminist, unreconstructed left-winger, with literary tastes that ran to recherché writers’. (The first-person, almost essayistic voice, tempts us to speculate on how autobiographical this novel is. It is a matter of public record that Jennings’s own experiences and background are similar to those of her heroine: faced with her older husband’s Alzheimer’s, Jennings took on work as an economic speechwriter and journalist in order to pay for his care.)

The tension between Cath’s background in 1970s activism and her growing expertise in finance means that, while she has the authority to offer a detailed understanding of economics, she is leery of applying it as a scientific truth or of separating the personal from the political. Instead, she proceeds with a dry intelligence to place both narratives side by side.

As she learns to distinguish between Brownian motion, game theory, fat tails, dynamic heritage and arbitrage, Cath discovers that the world of high-powered economics is as strange and irrational an Alice-down-the-rabbit-hole world as Alzheimer’s. Instead of invoking ‘moral hazard’ to correct markets, entities like the World Bank have a zealous faith in the power of markets to correct themselves. At the same time, Cath negotiates the baroque intricacies of an American health system in which spouses must hire assistants to make sure that their partners receive clean diapers in nursing homes, and must be ‘pauperised’ to receive Medicaid. The moral crisis that Cath faces in terms of prolonging Bailey’s life coincides with the world financial crisis of 1997 when this infinite speculation appeared to come home to roost. (Is this an Australian novel? Cath dispenses with the question quickly at the beginning: Australianness can be a matter of exported attitude, the ‘fine art of undercutting ourselves’.)

Yet these connections are not made too explicit. What is powerful and refreshing about Moral Hazard is the way that the novel allows Cath’s two lives to sit in apposite juxtaposition. Instead of trying to fit her material to an overriding allegorical scheme, Jennings allows connections to make themselves. The details of Bailey’s Alzheimer’s – terrible, brief, unsentimentally recounted – are more heartbreaking because of the sense that they run their course within a system that appears to care but is as carelessly random as the free market. At the same time, Cath’s aloneness is sad and familiar, but heightened by her dry-eyed understanding of her lack of importance in monetary terms.

It is a pity that the flinty, precise elegance of Moral Hazard is undercut by its layout. Huge chapter numbers sit at the top of very short (sometimes two-paragraph) chapters. While the book should have had the cumulative, essayistic effect of Paul Auster’s Invention of Solitude, which makes use of breaks between its scenes and thoughts, these glaring chapterisations sometimes give a false sense that Jennings’s book is a flimsy novel.

While Moral Hazard is sceptical about the possibilities of finding any higher truths, Joanna Murray-Smith’s new novel, Judgement Rock, a chamber drama for three characters, fervently searches for them. Tasmania (or, in this case, the remote islands off the Tasmanian coast) seems to have become Australia’s symbolic heart of darkness over the last few years, a nowhere place onto which allegorical images can be projected, or a kind of wilderness area remote from the outside world in which the nation’s own primal dramas can be played out. Murray-Smith’s novel falls somewhere between the two.

The island’s isolation is what has attracted the heroine, Iris, a botanist in search of the rarely sighted, possibly extinct, flame orchid. Iris is aware that islands are highly significant for scientists, as they are isolated places where it is possible to test science’s own limits: its desire to ask questions, its desire for hard edges, for beginnings and endings. Iris ends up marrying the lighthouse keeper, Noah, although it is questionable whether what they feel for each other is love. Halfway through the novel, a mysterious sailor called Joe is shipwrecked, comes to live with Iris and Noah, and brings darker passions to play.

Judgement Rock offers an odd mix of realism and symbolism, a hard narrative act that it does not quite manage to carry off. The island setting is delicately observed, but the trouble is that it offers too many symbolic structures (islands, Judgement Rock, the flame orchid) and too many big questions, and tries to resolve them all.

Comments powered by CComment