- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Robert Menzies cast such a large shadow that the contribution of his immediate successors has tended to be belittled, if not forgotten altogether. Each of the three is remembered mostly for things unconnected with their prime ministerships: Harold Holt for the manner of his death; John Gorton for his drinking ...

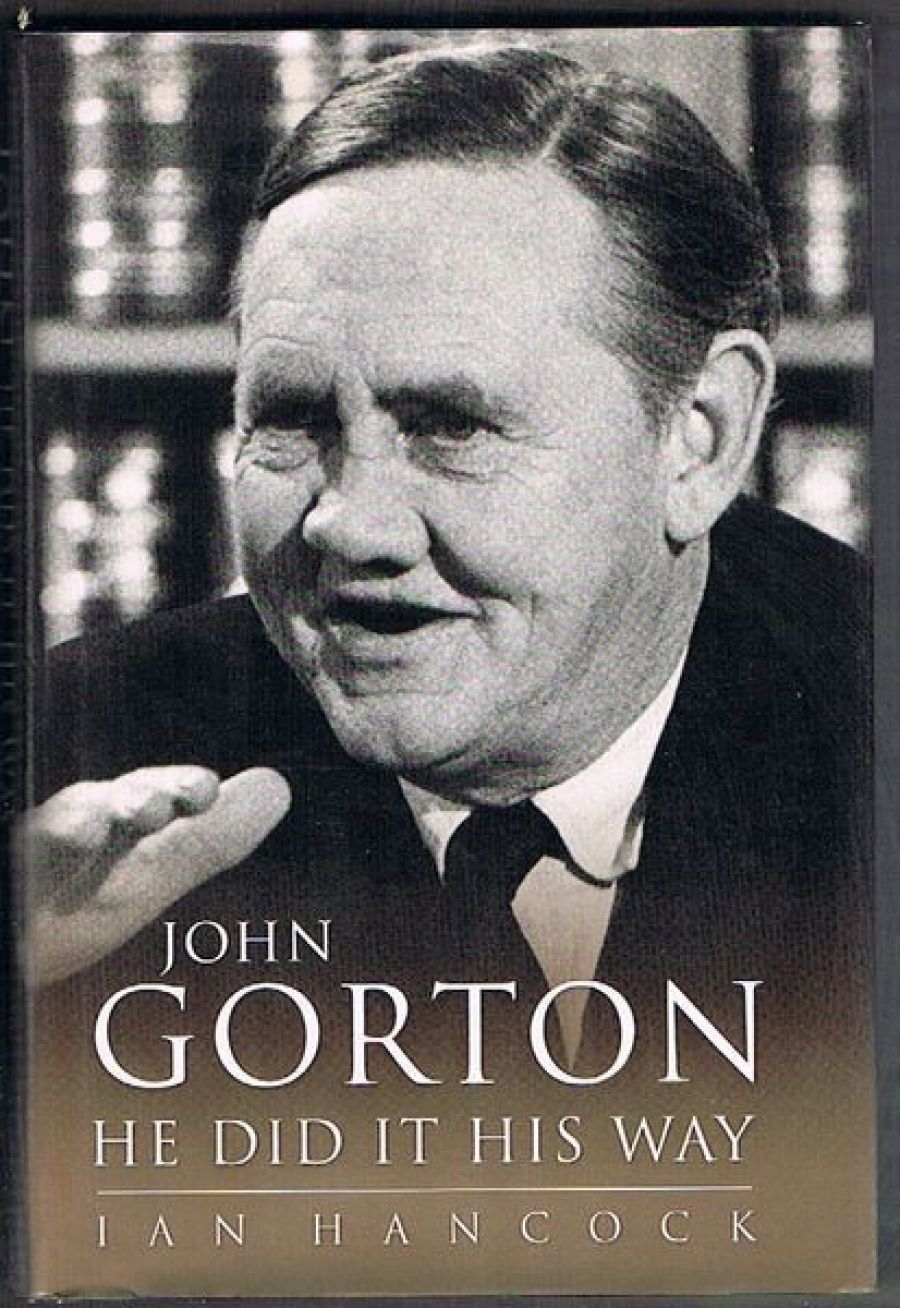

- Book 1 Title: John Gorton: He did it his way

- Book 1 Biblio: Hodder Headline, $50 hb, 446 pp, 0733614396

For all the emotional impoverishment of these formative years, Gorton’s later childhood was not marked by material impoverishment. He lived for a time on Sydney’s North Shore and was sent to one of its best schools before fetching up at Geelong Grammar. He became a prefect under the beneficent tutelage of its influential headmaster, James Darling, who suggested to Gorton that one day he might become prime minister. And it was Darling who pressured Gorton’s father into sending young John off to Oxford, presumably so that he might have a chance of fulfilling this destiny.

Hancock’s treatment of those years in Oxford is disappointing. There are details of Gorton’s sexual relationship (his first) with an older, married woman, but no reflection on what it might have meant to Gorton. Other interesting questions are similarly left unexplored. For instance, what effect did Gorton’s experience in 1930s Oxford have on his sense of Australian identity? What mental images of Britain did he carry with him to Oxford, and how did they accord with his experiences? Did his three and a half years in England play any part in the political development of this particularly Australian-minded prime minister?

This traditional political biography is strong on the internal workings of the Liberal Party, on which Hancock has previously written, but devotes little attention to Gorton’s life outside politics. His first wife remains a shadowy figure in the story, while his children disappear completely from the time he enters the Senate until well after his retirement. Nearly half the book is devoted to the three years that Gorton, now ninety, was prime minister.

Despite this, readers are regaled with details of what he might have eaten during a summer trip to Spain and informed that it cost the Oxford undergraduate a shilling to stay in a boarding house in Hull prior to his working for two weeks on a fishing boat in the North Sea. One wonders about the relevance of this. Was a shilling expensive for the times? Does it matter? More interesting is the fact that Gorton and his companion spent the night in a haystack on their return journey to Oxford. That at least says something about young Gorton. There are several other lapses of historical discernment, such as when we are told that padded postal bags were introduced in 1970, as if that were significant.

Gorton returned from his days at Oxford with a respectable second-class honours degree and an American wife, Bettina. It should have been a triumphant homecoming, but he was greeted on the Melbourne wharf by a father who was clearly unwell and who died the following year. Hancock briefly sets out the facts of what must have been a trying time for Gorton, the death of a father whom he was said to have ‘idolised’ but who was forever disappearing from his life. Now he had gone for good, leaving Gorton a legacy of a debt-burdened orange orchard near Kerang in northern Victoria. It would have been helpful to know the emotional effect on Gorton of the death of this man who, Hancock suggests, bordered on being a con man and who always ‘Lived on the brink of a fortune, that never quite materialised’.

Gorton was forced to abandon the journalistic career that his father had arranged for him. Undaunted, he set out with his wife and revived the fortunes of the orchard, dislodging his father’s mistress. And there the story might have ended, had it not been for the Second World War and its political aftermath.

It was Chifley’s attempt to nationalise the banks that propelled Gorton into political life in 1949. Gorton’s striking facial appearance reminded voters of his wartime experience as a fighter pilot: in a crash landing during the defence of Singapore, his face had been smashed into the gun sight. Doctors did what they could to repair the damage, but he was still left with the putty-faced look of a second-rate prize-fighter.

A staunch anti-communist and supporter of the White Australia policy, Gorton in the Senate gave little indication of his future rise to prominence. Prior to gaining the prime ministership, he had served only as Navy Minister and then Education Minister, and had a relatively low public profile. Hancock is particularly strong on the political machinations that allowed Gorton, with the strong support of the Country Party, to be anointed as leader of the Liberals. They would come to rue their selection.

Gorton distinguished himself as prime minister by adopting relatively nationalistic stands on such matters as foreign investment and the future of Australia’s foreign and defence policies. They were stands that disturbed many of his Liberal colleagues, as did his centralist tendencies in Commonwealth–State relations, which saw him overruling the Queensland government to protect the Great Barrier Reef. Such moves gradually eroded his support within the party and made his eventual overthrow more likely. However, as Hancock makes clear, it was probably his buccaneering and relatively authoritarian political style that was his undoing. This was exemplified by the appointment of the 22-year-old Ainsley Gotto as his principal private secretary and his taking a 19-year-old female journalist along to a late-night briefing at the US Embassy. Both actions scandalised some of his more censorious colleagues and caused headlines in the press. It was not the suggestion of womanising per se that prompted the outrage. It was that he had allowed his apparent proclivity to besmirch his high office.

Gorton’s suitability for the top job was tested at the 1969 election, which saw the Labor Party’s vote, under Whitlam, rise by nearly seven per cent. When the Senate election in 1970 underlined the slump in government support, the critics sharpened their knives. After his fall from power in March 1971, Gorton became a vitriolic critic of his successor, McMahon, and an unforgiving hater of Malcolm Fraser, the erstwhile supporter who had done much to bring him down. It is Fraser who is now out in the cold, as far as the Liberal Party is concerned, and Hancock loses few opportunities to take a swipe at him.

Hancock’s authorised biography paints a portrait of a politician who some said could have been a great prime minister had he not been brought down by lesser mortals. Not that this is hagiography, for Hancock concedes the failings that would rob Gorton of any claim to greatness. He was a devil-may-care politician who found himself shoved to the front, only to be caught out of his depth. By his own admission, Gorton took to drink to cover his confusion. An accidental prime minister, he became an accident waiting to happen.

Comments powered by CComment