- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Gay Studies

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

This is a strange assortment of pieces. To someone who doesn’t move in any gay community, the anthology’s chief problem is its fissiparousness. There has to be a distinction between gay writing and writing by authors who are gay. The majority of contributors to Graeme Aitken’s book take gay life to be their subject, but several are included because they are gay, while not necessarily employing gay themes, or doing so indirectly.

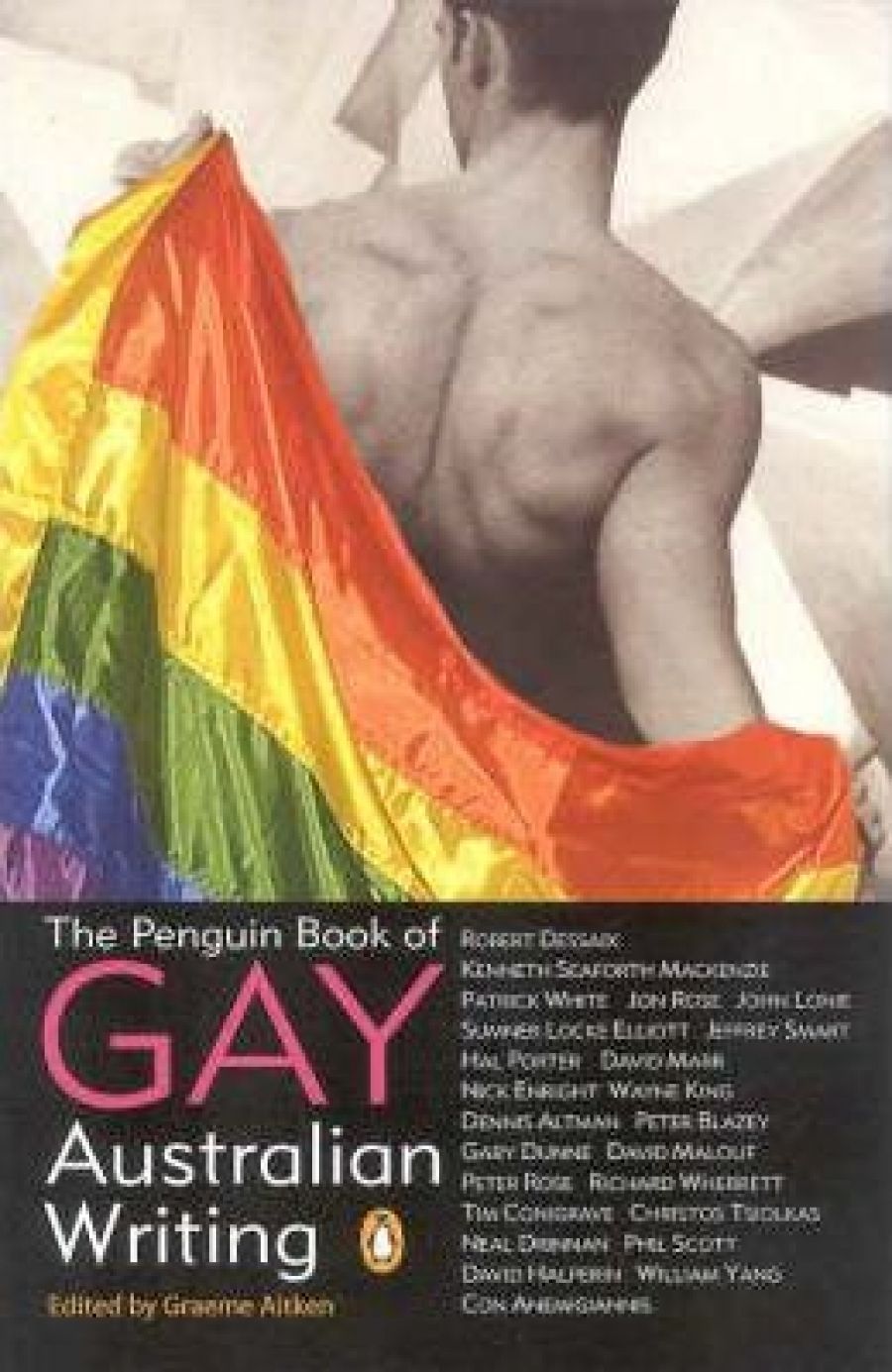

- Book 1 Title: The Penguin Book of Gay Australian Writing

- Book 1 Biblio: Penguin, $29.95 pb, 422 pp, 0 14 300001 2

Well, they are, if their preoccupations are with how gay men and especially gay youth behave in Australia today (or even how they were forced to behave in the recent past). Both Aitken’s Introduction and Michael Hurley’s Critical Reflection are confused in their approach. On the one hand, Hurley asserts: ‘For those who love reading gay writing, it is the fact that it is writing which matters.’ A little later he remarks: ‘The Editor’s focus is gayness: of the writers and of the stories.’ The ground covered is wide – categories include pioneers from the days when direct reference was necessarily veiled (Kenneth ‘Seaforth’ Mackenzie, Hal Porter, even as late as David Malouf); polemics and histories both personal and social (Dennis Altman, David Marr, Jeffrey Smart, Peter Blazey, Richard Wherrett); works of fiction, stories or extracts from longer works (the rest of the contributors, notably Timothy Conigrave, Christos Tsiolkas, Phillip Scott, William Yang, and Neil Drinnan). The level of frankness increases as the book proceeds, and with it comes a sort of truculence. Emancipists argue from a sense of fairness: celebrants are ruffled only by AIDS. If this is a watershed, it is an entirely proper one.

Among the pioneers, Mackenzie’s public-school scene from The Young Desire It stands out. Beautifully written, it evokes the world of Frederic Manning’s Her Privates We, with agonised decorum reaching out to scarcely hidden emotions. ‘Action can wait,’ his thoroughly aroused schoolteacher observes after tending to a boy injured at gymnastics. Nevertheless, the tone is as distant from today as Tom Brown’s Schooldays. Porter’s ‘Francis Silver’ seems even more remote, reminding us of a time when homosexuality produced worried adjectives such as ‘sissy’ and ‘pansy’, precursors of such terms as ‘queer’ or ‘camp’. Sumner Locke Elliott is direct enough but sticks to gossipy dialect reminiscent of Evelyn Waugh and Anthony Powell.

Once explicitness sets in, tone divides into sombre real-ism and romantic idealism, though the second of these remains explicit of physical detail. The extract from Tsiolkas’s Loaded combines the two manners. A brilliant piece of writing, it snatches from a realistic description of drug addiction and casual sex a nimbus of family affection qualified by eccentricity and squalor. Romanticism is widespread, notably in Scott’s ‘Your First Time’ and in the extract from Conigrave’s Holding the Man, which conjures up feelings rather too easily associated with adolescent awakening – innocence and bewilderment – but made manifest here in a gentle account of finding sexual valency in a Melbourne Boys School.

Most of the fiction writers are relentlessly up to date, reinforcing the impression that Australia is determined to turn its eyes away from the past. Gary Dunne’s ‘Eating Cheese-cake’, Yang’s ‘Grafton’ and the quotation from Neal Drinnan’s Pussy’s Bow are as genitally prescriptive as a medical textbook. Wayne King’s report on gay hatred in the indigenous community is a disquieting burst of polemic.

The polemicists themselves are more reasoned in attitude, especially Marr, whose article on Christian persecution of gayness is acutely argued. Contributors’ Notes remind the reader of the bleak background shared by many gay writers. Three of those who appear here have died of AIDS, which may make my final comment seem untoward. Much the most remarkable contribution is Con Anemogiannis’s description of growing up in a Greek boarding house in Sydney’s Newtown, taken from his novel Medea’s Children. You could not imagine a more amoral piece of writing, nor yet one more filled with humour, joy and extravagance. The young author spies on his mother’s beautiful Greek tenants in the bathroom, and both pleasures them and is pleasured by them from early adolescence onwards. Shameless and graceful, Anemogiannis scatters happiness and reassurance about him as freely as he does semen. I would not have guessed how exhilarating such a dithyramb to the Aphroditean ectoplasm of the young male could be.

Comments powered by CComment