- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Timely reminders

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

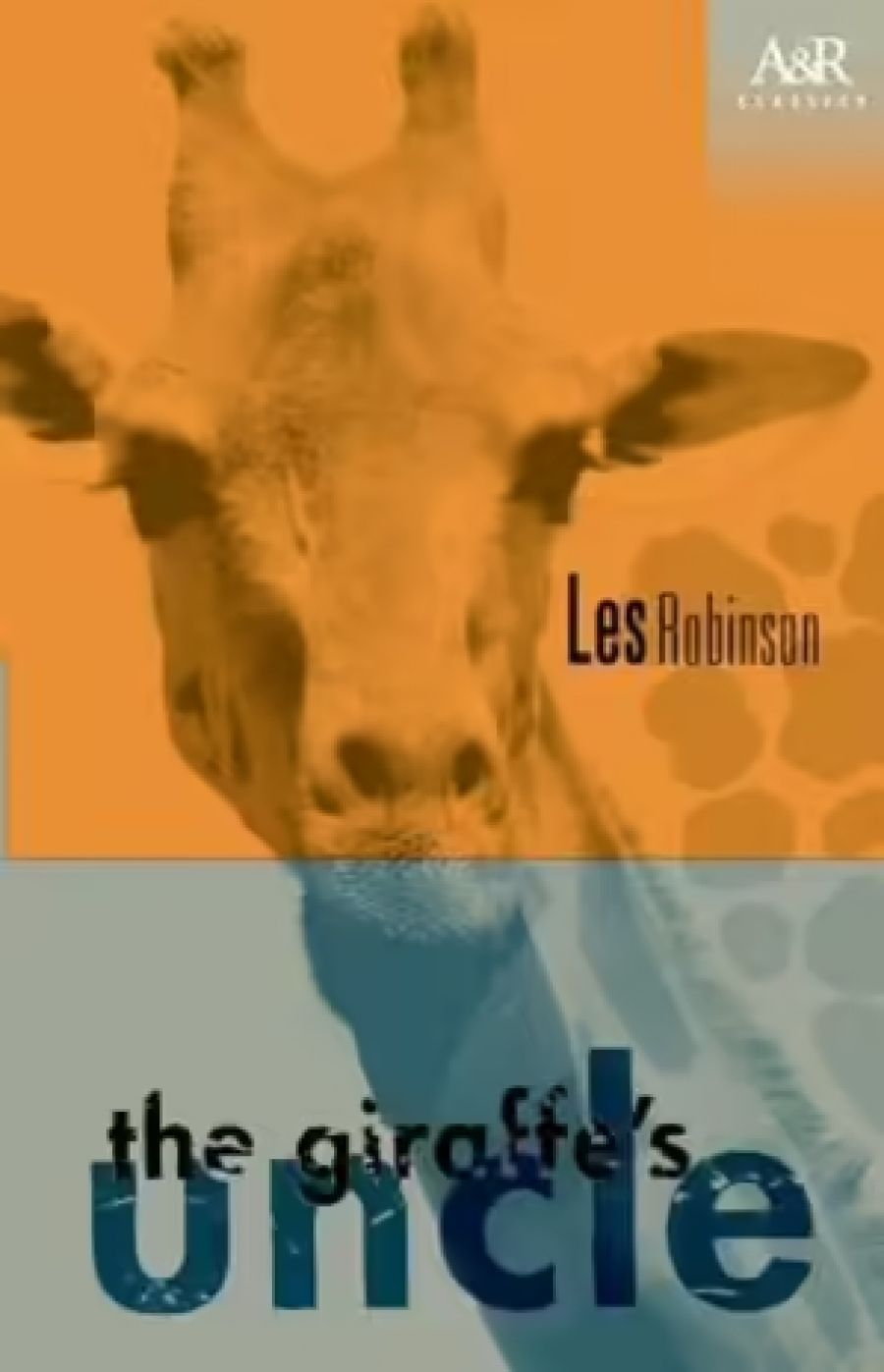

As HarperCollins continues to release this welcome series of Australian reissues, it’s especially pleasing to see them including less well-known, even long-forgotten, titles. While I had read none of these latest offerings, I did at least know something about three of the authors. Les Robinson, however, was almost a complete mystery. ‘Almost’ because I had a vague memory of one of his stories being included in an anthology I once lectured on. Obviously, it did not impress me enough to seek out more of his work. Nor would it have been easy to find, since, unlike the other three titles, The Giraffe’s Uncle had never been reissued since its first printing, in 1933, by the Macquarie Head Press, a firm now as forgotten as the books it published.

- Book 1 Title: The Giraffe's Uncle

- Book 1 Biblio: A&R Classics, $22.95 pb, 116 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: https://www.booktopia.com.au/the-giraffe-s-uncle-les-robinson/book/9780207199578.html

- Book 2 Title: My Love Must Wait

- Book 2 Biblio: A&R Classics, $24.95 pb, 511 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Readings Link: https://www.booktopia.com.au/my-love-must-wait-ernestine-hill/ebook/9781743099339.html

Chris Mikul, introducing this new edition, provides some fascinating details of Robinson’s life. One of those legendary Sydney bohemians of the 1920s, his main claim to fame was a preference for living in caves by the sea. While not a member of the nationalist literary circles then promoting Joseph Furphy’s Such is Life, Robinson would clearly have endorsed its famous opening line: ‘Unemployed at last!’ He contributed stories, articles, and cartoons to various Australian literary and comic magazines, but otherwise worked as little as possible. This may be why ‘The Week I Worked’ stands out as one of the gems in this collection. It opens, ‘I do not like work. I never did. It interferes with one’s digestion’, before recounting the total mayhem of the week when the narrator is let loose in a factory.

Kenneth Slessor’s introduction to the 1933 edition describes Robinson as ‘an exiled stylist’ and laments the fact that he has been forced to ‘join the chain-gang of the clowns’ in order to get published. While Robinson’s humour is never as broad as that of his contemporary Lennie Lower, many of his stories depend on comic exaggeration, with one calamity following another, whether the narrator is attempting to move house or go to the seaside for a rest. ‘Ferdinand and Jolinquitus’, singled out by Slessor as a piece more likely to be appreciated in 1993 than 1933, is very different in tone and style. Concerned with a meeting between Ferdinand and the mysterious Jolinquitus, ‘who appeared suddenly, as though from nowhere, like some monster in the menagerie of a dream’, this fable immediately upsets the reality/dream binary, with Jolinquitus pronouncing: ‘that man on the sand there is extinct.’ ‘Song of the Flea’, where the narrator is simultaneously both a flea and the sleeping human body on which it feeds, is equally dark and unsettling. Stories such as these, which look back to the more fantastical work of Marcus Clarke and forward to Peter Carey and Michael Wilding, show that Robinson deserves a place in any history of short fiction in Australia.

Unlike the best of Robinson’s stories, Ernestine Hill’s My Love Must Wait, subtitled The Story of Matthew Flinders, is very much a product of a particular time and place. Originally published by Angus & Robertson in 1941, it is understandably full of nationalistic sentiment, ending: ‘While the old order crumbles in Europe, in the new world that we shall build, Australia, continent of his naming, faces the dawn.’ Like the celebrations of the Sesquicentenary of 1938, Hill’s version of Australian history is a paean to heroic masculinity, science, discovery, and progress. Convicts and indigenous Australians, so central to recent historical and fictional accounts of our past, appear here only as comical or irritating minor presences. Bennelong ‘gibbers’ and parades in all his misplaced London finery; convict women ‘brazenly showed their nakedness with ribald jokes and curses’. The novel is at its best recounting small personal moments, where Hill had to depend more on her imagination. But, for those interested in Matthew Flinders, any of the new works issued this year to celebrate the two-hundredth anniversary of his circumnavigation of Australia would probably be a better buy.

By the 1950s, thanks in part to the continued crumbling of the British Empire, the hero of an Australian historical novel was more likely to be an ordinary battler in the bush than an English explorer. Jon Cleary’s The Sundowners, first published in London in 1952, interestingly anticipates by a few years Vance Palmer’s and Russel Ward’s claims for the nomad tribe of bushmen as the archetypal Australians. Paddy Carmody, drover, shearer, gambler, drinker, is described as being totally at home in the bush; indeed, ‘He was the colour of the countryside’. While no longer one of the ‘Lone Hands’ of the 1890s, Paddy still refuses to settle down, and his wife and son have to make the best of it. As bushfires, shearing contests, two-up games, and horse races follow each other in rapid succession, the Carmodys survive both good and bad times with grit and humour. Cleary does, however, also depict some of the actualities of bush life: hard work, loneliness, poverty, not to mention much casual sexism and racism. Published near the beginning of a writing career that has now lasted for over fifty-five years, The Sundowners is the product of a more innocent time and a more innocent Australia, but also of a master storyteller.

A different, and far from innocent, Australia is described in Peter Kocan’s two novellas of the 1980s, The Treatment and The Cure. One of the surprisingly few people ever to attempt to assassinate an Australian politician (he shot and wounded ALP leader Arthur Calwell in 1966), Kocan’s subsequent ten years in penal and psychiatric institutions provided the material for these ironically titled works. Like Kocan, nineteen-year-old Len Tarbutt, despite the treatment he receives, survives because of his own inner resources and his discovery of poetry. For Len, as for Janet Frame some decades earlier, literary success provides the real cure, establishing his right to be treated as a person, rather than a thing. Tellingly, Len comes closer to giving up in the relative freedom of the ‘retard’ ward than he ever had in maximum security, thanks to inappropriate medication and being treated as, at best, ‘a bright five-year-old’. But an awareness that suicide would be seen as a vindication of the system – ‘Poor deranged Tarbutt! If only he’d responded to treatment!’ – keeps him going. Are things any better now? One hopes so, while realising that institutionalised power will always result in the kinds of petty, and not so petty, persecution so chillingly depicted by Kocan.

Slessor ends his introduction to The Giraffe’s Uncle by claiming that Les Robinson’s stories are ‘all quite useless’. While taking his point, I wish to disagree. Robinson’s best pieces, like Kocan’s novellas, take us into places we might not otherwise enter. Moreover, in their different ways, these four reissues remind us what it means to be human.

Comments powered by CComment