- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: East Timor

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Mute dilemmas

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The publisher’s blurb that accompanied my review copy of Joseph Nevins’s book makes two prominent assertions. One is that the United Nations has given Indonesia a six-month deadline to prosecute war crimes committed in East Timor in 1999. The other is that Paul Wolfowitz, a former US ambassador to Indonesia and an architect of the 2003 US invasion of Iraq, was complicit in East Timor atrocities. I suppose such attention-grabbers are needed to sell books in today’s over-saturated literary markets, but these two do little justice to the broad sweep and value of Nevins’s latest work. (Under the pen name Matthew Jardine, he has written two others on East Timor, and is something of an activist on the subject.)

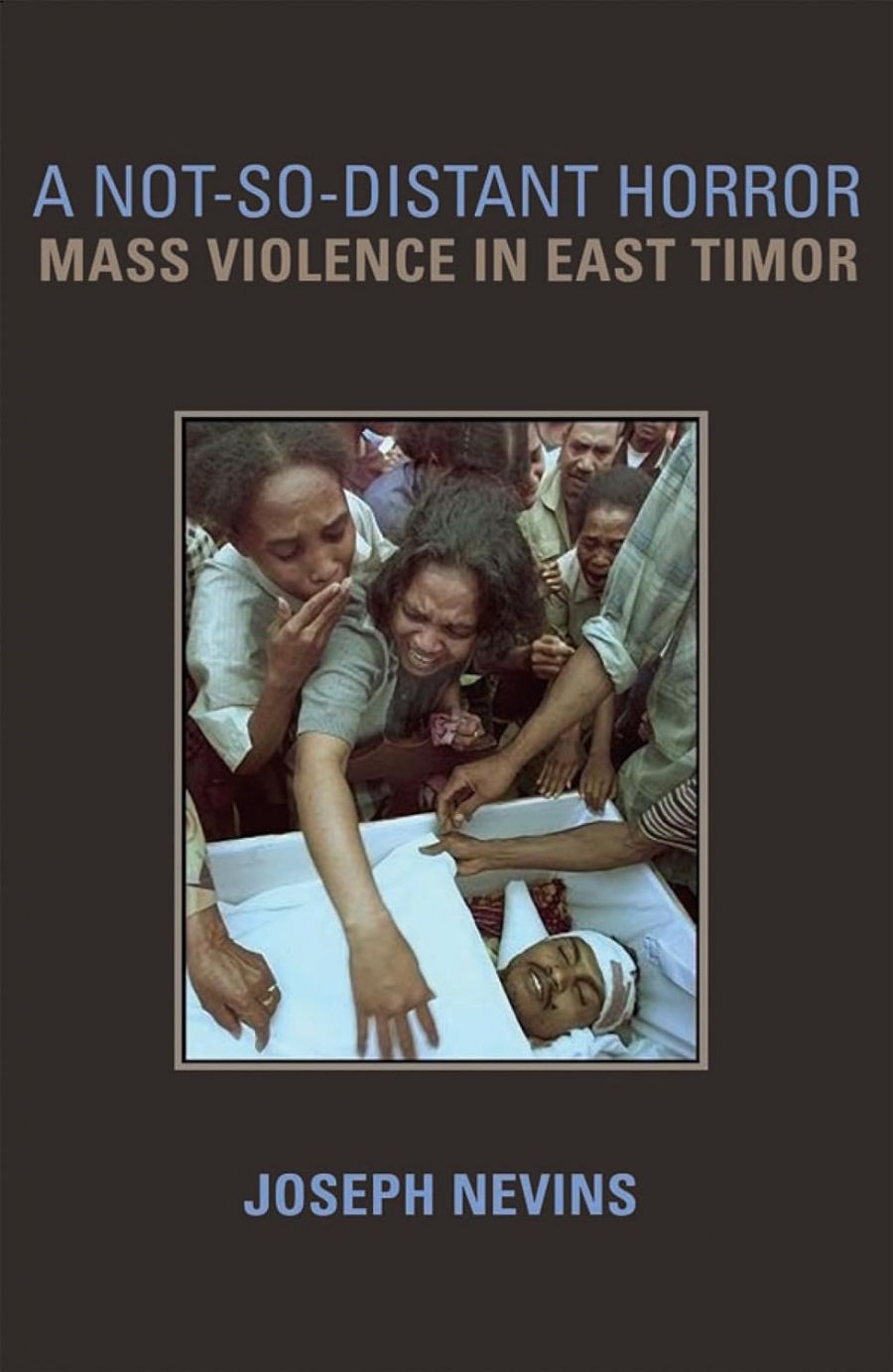

- Book 1 Title: A Not-So-Distant Horror

- Book 1 Subtitle: Mass violence in East Timor

- Book 1 Biblio: Cornell University Press, US$49.95 pb, 273 pp, 0801489849

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Nevins’s account of the period from Indonesia’s unlawful invasion of East Timor on 7 December 1975 to the withdrawal of its forces in September 2001 is factual, accurate and spare. Indonesian forces invaded East Timor in December 1975 and annexed the neglected Portuguese colony six months later. During the following twenty-four years, Indonesian forces and the local militia that they controlled and equipped killed 200,000 people – one-third of the population – forcibly removed to West Timor another 300,000 to prove that the Timorese wanted ‘integration’, destroyed most infrastructure and buildings, and diverted millions of dollars in World Bank funds to propagandise for East Timorese ‘autonomy’, and to fund military terror. Most of the atrocities were concentrated in the month of September 1999, following a UN-run ballot on August 30 to decide whether the Timorese wanted integration with Indonesia or independence. The Timorese voted overwhelmingly for independence, and were rewarded with indiscriminate massacres. One of the main perpetrators was Eurico Guterres, chief of the Dili-based Aitarak (‘thorn’ in Tetum) force. Aiding and abetting him was Abilio Osorio Soares, governor of East Timor at the time. Armed, equipped and supported by the TNI, Guterres and his thugs killed and raped indiscriminately. It was payback for the Timorese who dared to vote for freedom. With Indonesia’s grudging permission, extracted by President Clinton, the Interfet force led by Australia entered East Timor on September 20. It was far too late to stop the killings, forced repatriations to West Timor, or wholesale destruction of infrastructure and property.

Nevins recounts how, during most of this period, the international community stood by and did nothing to alleviate the situation. Indeed, the US, UK and France continued to supply sophisticated anti-insurgency weapons to the TNI; Australia and New Zealand continued to train Indonesian forces; and Japan adopted a neutral position while continuing to buy Indonesian oil. Former US Ambassador to Indonesia, Stapleton Roy, summed up the situation to the London Financial Times on 8 September 1999, when he said: ‘The dilemma is that Indonesia matters and East Timor doesn’t.’

During a visit to Jakarta in November 1999, US Ambassador to the UN, Richard Holbrooke, told a gathering of diplomats that Americans believed profoundly in accountability, which was, he said, ‘one of the two or three keys to democracy’. But in the months and years since, East Timorese have received little accountability, let alone justice. The majority of human rights violators in the TNI and militia have not stood trial. No international tribunal has been sanctioned by the Security Council. Jakarta has not agreed to the kind of sub-judicial truth commissions that gave South Africans solace and release from crimes perpetrated against them. The scope of ad hoc courts set up to try TNI members was limited by Megawati Sukarnoputri to crimes they allegedly committed solely during the months of April and September 1999. Meanwhile, the East Timorese Governor Soares was released on appeal by an Indonesian court, and the militia leader Guterres had his sentence reduced from ten to five years.

Nevins draws some wide but convincing conclusions from these events. He believes that they have undermined the reconciliation process between the different factions of East Timorese wanting integration or independence. They have had profoundly detrimental implications for the people of Aceh, West Papua and others fighting for independence or autonomy. In a global context, Nevins asserts they provide yet another set of the double standards of people and governments in wealthy countries. Other examples he cites are President Reagan’s rejection of the findings of the International Court of Justice on US violence in Nicaragua; US attempts to prosecute the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia without acknowledging its own crimes there during the Vietnam War; Jimmy Carter getting the Nobel Peace Prize in 2002 despite having provided the TNI with weaponry with which to kill tens of thousands of East Timorese. And, Nevin suggests, during the outpourings of rage and grief in the US over the destruction of the World Trade Centre, few Americans recalled that on the same date in 1973 the United States overthrew Salvador Allende in Chile and installed Augusto Pinochet, who arranged thousands of civilian murders. Most were unaware of the long list of assassinations and coups, even against elected leaders, that US administrations had carried out in their name.

There is much to reflect on in Nevins’s book, not least the mute acceptance in Australia of many US policies as our own.

Comments powered by CComment