- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The hero buisiness

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Australia has never been so prodigal of great men that it can afford to let even one slip into oblivion; yet George Hubert Wilkins (1888–1958) is now hardly a household name. In a life of ceaseless activity, he was a photographer, naturalist, meteorologist, geographer, aviator, submariner, war correspondent, religious thinker, and writer, but he was best known as a celebrated polar explorer. His first biographer, John Grierson, a professional writer, dealt adequately enough with the many lives of Wilkins in 1960, at a time when his subject was still well known. Four decades later, Simon Nasht, a documentary film-maker, offers the Australian reading public an expanded version of Grierson’s biography. Nasht has the advantage of a growing library of polar studies, and his book appears at a time when climatology and extinction of species are subjects of scientific and popular concern.

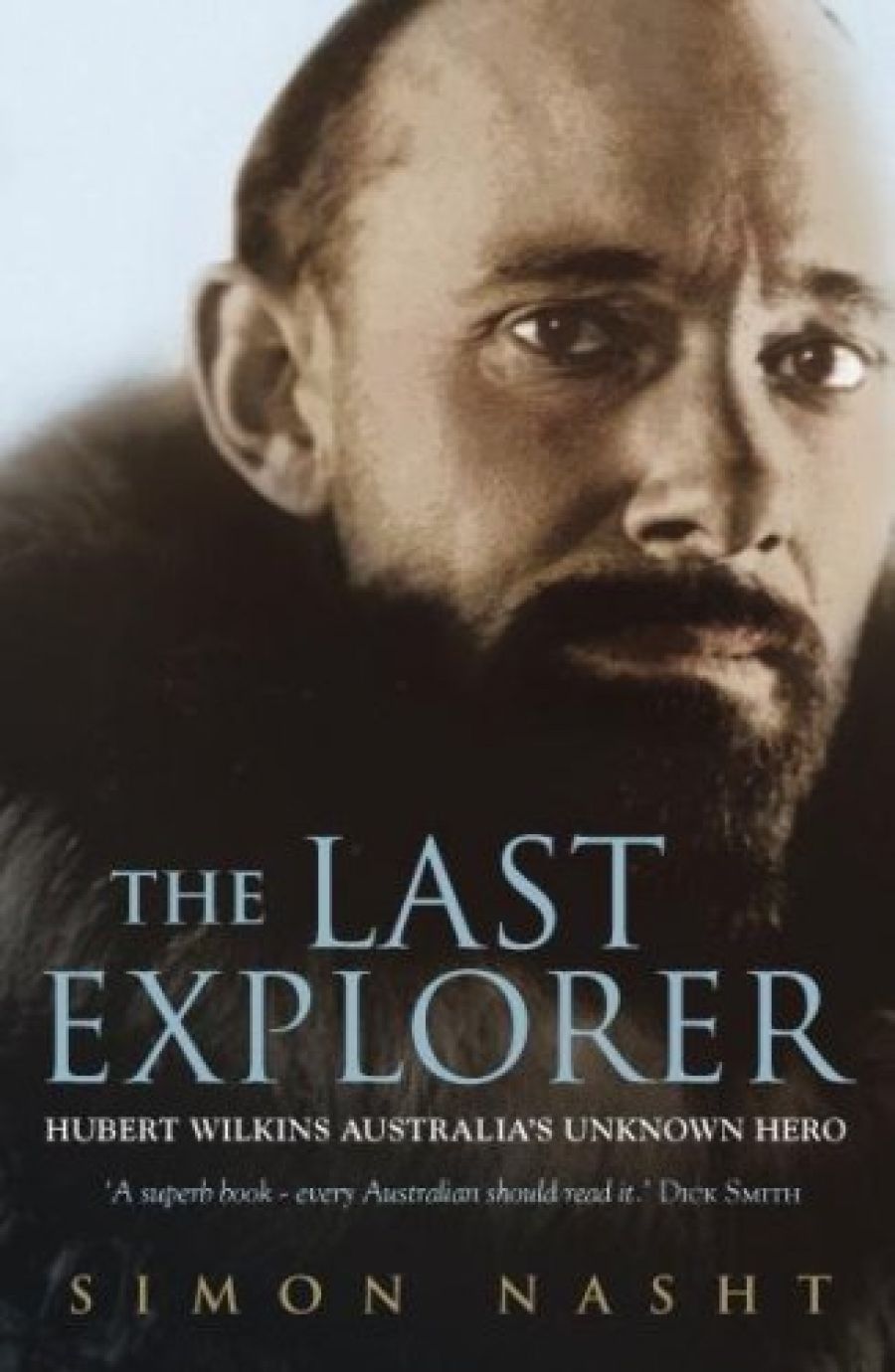

- Book 1 Title: The Last Explorer

- Book 1 Subtitle: Hubert Wilkins, Australia's unknown hero

- Book 1 Biblio: Hodder, $35 pb, 346 pp, 0733618316

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

It doesn’t help that Nasht has chosen to narrate the story himself, rather than allow Wilkins’s voice to be heard as often as possible. Even in the hands of a master, paraphrase grows pedestrian in tone. Nor does it help that Wilkins appears to have had little private life, no permanent retreat, which would have enabled Nasht to vary the pace and mood. What the reader is given is a blow-by-blow account of a life lived at the edge of physical endurance, with numberless encounters with imminent death. Even reading this in a comfortable armchair is an exhausting business.

Despite these caveats, the new biography achieves its aims. It details Wilkins’s remarkable achievements by sea, land and air in the Arctic and Antarctic. It explains his abiding interest in a worldwide network of meteorological stations. It demonstrates that in some of his thinking he was decades ahead of the scientific establishment. Wilkins grasped instinctively the uses of aerial photography and aviation when these were in their infancy. The book chronicles his diverse activities, in the First Balkan War, when he faced a firing squad; then as a much decorated photographer in France in 1917–18 (‘the bravest man in the army’, John Monash is reputed to have said); later investigating the first Russian famine and supposedly meeting Lenin shortly before his death; then in northern Australia, on naturalist expeditions for the British Museum; flying on the Graf Zepplin; pioneering moonlight flying in the Arctic during winter; decorated by Stalinist Russia; and attempting a submarine crossing under the North Pole in 1931, a failure that exposed him to much ridicule.

Religion (unlisted in the index) was of fundamental importance to Wilkins. In his introduction, Grierson provided a prayer that Wilkins wrote, as a key to his spirituality. Brought up in a strict Methodist family, Wilkins believed in a God, an unseen force, intervening at moments when he faced death. Wilkins also believed in telepathy, and jointly wrote a book on his investigations. Most interesting of all was his membership of the Seventy, the inner circle of the Urantia movement, based in Chicago, which studied the spiritual origins of the universe.

Wilkins is a figure out of a John Buchan novel, a mixture of Hannay and Arbuthnot; he shares many of the traits of a Buchan hero (modest, brave, fearless of death, courteous, religious, impervious to suffering). It needs a writer of Buchan’s distinction and Calvinist mind to provide a worthy memorial to such a driven and enigmatic man.

The world of explorers, in which Wilkins cut such a distinguished figure, was densely crowded with ‘fatally flawed’ heroes, cranks, mountebanks, enthusiastic ignorant young men; pilots of remarkable bravery; some of the vainest liars of the day; men who, once exposed to the polar wastes, never again found peace; criminals, saboteurs and drunkards. The reader meets an extraordinary cast, including W.R. Hearst, Goering, L. Ron Hubbard and Admiral Rickover; as well as the great and not-so-great of polar exploration: Shackleton, Mawson (who, as Philip Ayres shows in his model biography, did not care for Wilkins), Byrd (a great rival), and oddities such as the explorers Stefansson, Cope and Cook. In this world of ferocious competition and driven personalities, Wilkins stands out for his modesty and ability to cope with the prickliest of men.

After 1909 Wilkins spent little time in Australia, but he remained a loyal subject of the empire. He based himself in the US and married there, although life on the move meant that he rarely saw his wife. Wilkins was still at work when he died, alone (as always) in an American hotel in 1958. In death, the US did him proud: a nuclear submarine surfaced at the North Pole and deposited his ashes there. It is a remarkable life, recounted for a new generation by Simon Nasht, which ought to be in every municipal library.

Comments powered by CComment