- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Language

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Monolinguists and xenophobes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

If anyone is qualified to speak authoritatively on the nature and role of community languages in Australia, it is Michael Clyne, who has spent much of his academic career researching these languages. His latest book is firmly rooted in research, but it differs from some of his earlier work in that it is clearly directed at the widest possible audience. It is a wake-up call, exploring the relationships between monoculturalism and multiculturalism and monolingualism and multilingualism in present-day Australian society; and showing how the present situation can be explained in part by Australia’s history, and in part by contemporary local and global pressures.

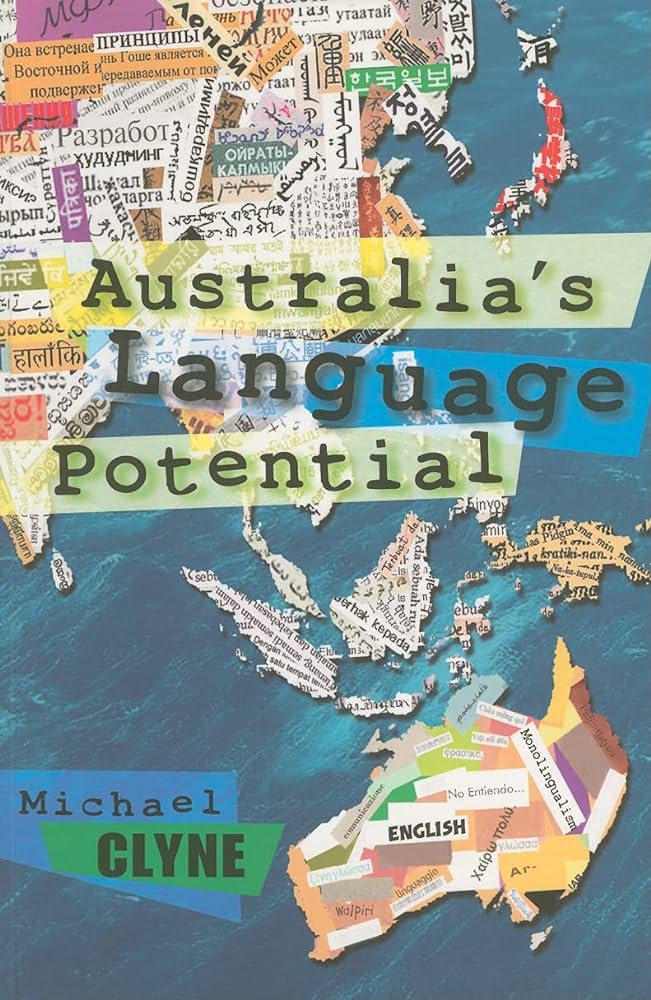

- Book 1 Title: Australia's Language Potential

- Book 1 Biblio: UNSW Press, $39.95 pb, 208 pp, 0868407275

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

For the first seven decades of the twentieth century, public policy denied and attempted to repress any manifestations of multiculturalism or multilingualism. This public policy was clearly expressed in a speech by the Minister for Immigration, Bill Snedden, in 1969: ‘I am determined we should have a mono-culture, with everyone living in the same way, understanding each other, and sharing the same aspirations. We don’t want cultural pluralism.’ But change came quickly in the 1970s and 1980s, leading to a situation where public policy valued linguistic and cultural diversity. The 1987 government report National Policy on Languages summed up the changes and provided directions for the future. Those two decades produced rich resources for the maintenance and transmission of community languages: radio, television, video, and print media (there are more than 180 newspapers published in Australia in community languages). But suddenly, in the 1990s, all this changed. The policies of economic rationalism in the early 1990s, and the later versions of monoculturalism evident in Pauline Hanson and John Howard, have meant that language policy and planning are off the political agenda. And Australia’s linguistic diversity is again under threat.

The malaise is evident, for example, in trends in the teaching of languages other than English. Arabic, Vietnamese, and Greek have some of the largest numbers of speakers under the age of fourteen (Arabic is first, Vietnamese is second, and Greek is fourth), but this is not reflected in the numbers of students taking these languages at school, or, more to the point, having these languages offered to them in schools. In an international context, Spanish is the most important language after English, but it is extraordinary how rarely it is offered in Australian primary and secondary schools.

The decline in the study and teaching of languages other than English in Australia might not simply be the result of apathy and xenophobia. It may well be a response to the notion that English has now become the global language. Clyne points out that to accept this notion is also to accept the role of English as a ‘killer language’, wiping out linguistic diversity and potentially the cultures that are carried by those diverse languages. But it is also to ignore the evidence of what is going on in other countries, where, in spite of the increasing use of English as a global language, there is also a worldwide increase in multilingualism, a trend that is especially evident in the European Union. Similarly, for some time it has been felt that English would continue its ‘killer language’ regime via the internet, but even there predictions are proving to be false: ‘Between 1995 and 1999, the percentage of home pages in English decreased from 84.3 per cent to 62 per cent and the trend is continuing.’ Paradoxically, the seemingly imperial advance of English has accelerated multilingualism, and it may well be that it will be the monolinguals who will be at a disadvantage in a multilingual world. Clyne fears that future generations of Australians will be disadvantaged if present language policy continues.

The value of linguistic diversity can be measured in various ways, from a narrowly economic perspective of business and economic profit to theories about the best ways of educating children. Clyne points to studies which show that bilingual children have a more sophisticated understanding of the nature of language than their monolingual peers, and in some areas have more developed cognitive skills. More important to Clyne are the moral and ethical issues. Languages are the carriers of cultural meanings and values, and it is perhaps only through languages that we can really understand other cultures. This is even true of English, for talk of ‘global English’ ignores the realities of regional variation, where it is those variations that carry the different cultural values. Clyne has seen Australia break free of its public imperative of monoculturalism and monolingualism in the 1970s and 1980s, but he laments that what has been achieved will be lost. More importantly, he laments the possibility that Australia will lose the linguistic diversity that is so important a key to understanding cultural diversity. This is an important and timely book.

Comments powered by CComment