- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: All’s well that’s Caldwell

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

'I knew I was bright, but not special’, writes Zoë Caldwell early on in her pithy, telling memoir. Still earlier (indeed, in the first paragraph), she says that she knew, even from an early age, she was destined to perform: ‘ … to stand in front of people, keeping them awake and in their seats, by telling other people’s stories and using other people’s words. I knew this because it was the only thing I could do.’ There is a bit of self-deprecation in these words that is at loggerheads with what we have come to expect from actors’ memoirs, which are, more often than not, scribbled sentences rather than thoughtful paragraphs, and which tell us more about vanity, greed, self-indulgence, and the patience of the haunted ghost-writer than they do about the actor as a professional or a person. Actually, such books are like sets on some early television shows: bricks-and-mortar, but really canvas and plaster with wooden backing, which wobble every time somebody walks past. What they are not is true autobiography.

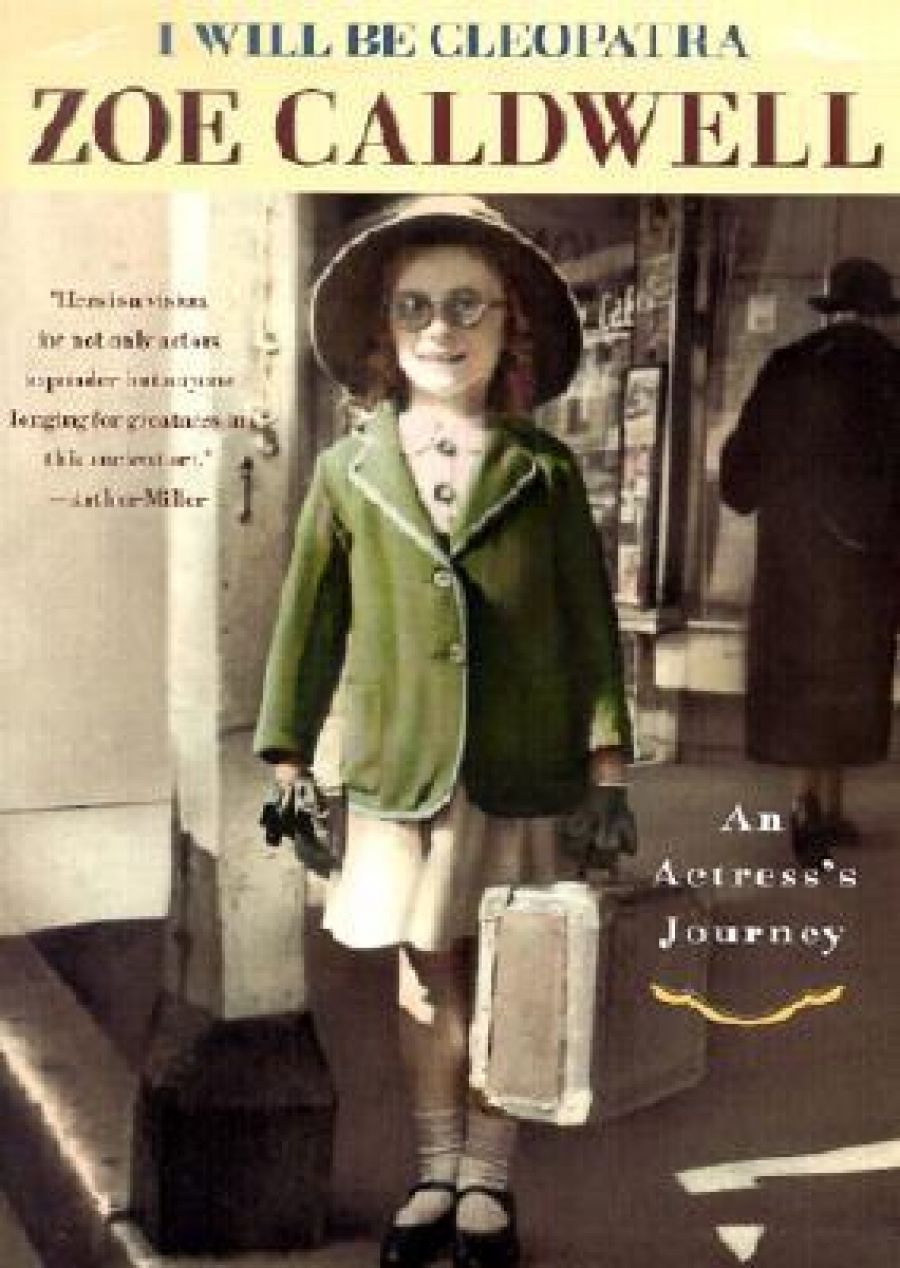

- Book 1 Title: I Will Be Cleopatra

- Book 1 Subtitle: An actress's journey

- Book 1 Biblio: Text, $28 pb, 173 pp

Zoë Caldwell’s I Will Be Cleopatra not only fulfils the principal requirement of autobiography – to bring the reader sufficiently into the world of the author to enable enlightenment, engagement, and feel a form of companionship – but exceeds it. It is not a long book, but, in 173 pages, Caldwell brings herself and her craft alive with vivacity, insight, humour, and conciseness; as with great plays, every word is put there to count, and not one is wasted. This is all the more surprising since Caldwell has never written anything before, and did this book by way of preparation for her three W.W. Norton Lectures at the New York City Public Library in October.

It is not just that Caldwell has a story to tell; it is how she chooses to tell it. Even the most incidental of facts is given purpose and clarity by her prose that conveys its effect often through imagery, but more often through what appears curious understatement, which is later clarified. Here she is, writing about her mother:

It didn’t help that she couldn’t spell and had no comprehension of punctuation, but she was not a fool. She had seen books and realised that proper writing required capital letters every now and then, and symbols that looked like dots and hooks with more dots on the end and little dots with tails. So whenever she finished a piece of writing, she would, it seemed, take a jug of punctuation and pour it over the page. No one could understand what she was writing; it remained her secret, until I became old enough and schooled enough to puzzle out her meaning and push all those strange signs into their rightful places.

Even with such a magical simile of a jug of punctuation (I want one, please), the story seems to end with the paragraph. But read on:

I am forever grateful to Mum for allowing me to correct her writing, because it taught me to follow the ‘score’ of a playwright and quickly know what he or she wanted to let the audience know. When I act, direct, or teach, I act, direct, and teach punctuation.

There is now a generation that might not have heard of Zoë Caldwell in the same way as past generations. Although she left Australia for good in 1963, and has not returned here since she opened the Victorian Arts Centre’s Playhouse as Medea, in 1984, she remains an indelible part of our theatre history as well as one of its most important actresses. Most of her career has been in England, Canada, and the USA, and she is a true theatrical, with only one film (improbably, Woody Allen’s Purple Rose of Cairo, in which she played a countess) and several long-forgotten English and Canadian television films to her credit.

Caldwell was born in Melbourne in 1933, educated at Methodist Ladies’ College in Hawthorn, joined the fledgling Union Theatre Repertory Company in 1953 (Barry Humphries and Ray Lawler were also in the company), then acted with the newly formed Australian Elizabethan Theatre Trust Company, playing the Second Woman of Corinth to Judith Anderson’s Medea; she worked for the Trust and the UTRC, and, in 1958, went to England, to the Shakespeare Memorial Theatre (now the Royal Shakespeare Company), at Stratford, where she eventually performed in various plays, opposite Albert Finney, Laurence Olivier, Edith Evans, Paul Robeson, Michael Redgrave, and Charles Laughton; she was with the company on its famous Russian tour in 1958, during which another Australian-born actress, Coral Browne, struck up a friendship with the defector Guy Burgess, a relationship immortalised by Alan Bennett in An Englishman Abroad. In 1961, Caldwell went to the other Stratford, in Ontario, where, among her roles, she performed Lady Macbeth opposite a young Scottish king who had trouble with his lines: Sean Connery.

It was at the Canadian Stratford that Caldwell made her début as Cleopatra, in Shakespeare’s Antony and Cleopatra, opposite Christopher Plummer. Her famous research into roles came into its own with the Egyptian queen:

It is said that Cleopatra had her pubic hair straightened, hennaed, and oiled, and that it was encouraged to grow as long as it could. The floors of her palace were shined so they could mirror this hidden beauty. I wondered if I should order a long silky merkin.

Caldwell ends her story here. Although I understand her reasons for wanting to do so (she maintains that Cleopatra was ‘the cornerstone of my career’, and after that she has no more to say), I admit some frustration in not having this wise and witty woman as the guide to the rest of her fine and noble career. Her return to Melbourne for Medea, her appearance as Maria Callas in Terrence McNally’s Master Class, indeed, her sole cinematic excursion, are all further adventures that would have beguiled us.

Still, I am grateful for at least this much, especially her tales of her early years in Melbourne, which include an affectionate insider analysis of John Sumner’s repertory company. Later on, in the early 1960s, Caldwell returned home, and performed in, among other things, Patrick White’s The Season at Sarsaparilla; during the Melbourne season, the playwright stayed in Caldwell’s family home, in Balwyn, in her brother’s sleep-out.

Her wise knowledge of theatre permeates the pages. Zoë Caldwell has much to say about acting in general, but usually beautifully crystallised into a paragraph, sometimes just a sentence: ‘The playwright will make the audience laugh or cry, not you’; ‘Talent then has to fill all your needs, all your desires, and if it doesn’t, you are truly alone’; ‘It is possible to chart a part so that always you know where you are and how much energy will be needed for the next part of the journey’; ‘Sex is such a strange thing in the theatre. You can look like a warthog, but if you have talent, you’re desirable.’ She does not give too much away about her personal life, but enough for us to know, for example, that she had an affair with Albert Finney and was named as co-respondent in his wife’s divorce action. She writes sensitively and tellingly about her relationship with the producer Robert Whitehead, whom she went on to marry; they now live in Westchester, New York, and have two sons in their thirties. I envy them their mother’s tales.

The book is filled with the musty scent of great stage stories, rather than over-perfumed recollections. I particularly loved her asking Dame Edith Evans why, before going on at each performance, she held her hands above her shoulders, shaking them: ‘I am simply draining the blood from my hands to make them as slim and white as possible.’

I long to read the transcripts of the Norton lectures, in case they reveal even more about the life and times of this remarkable actress, who has been away from Australia for far too long. Maybe, before too long, an equally wise entrepreneur or arts or writers’ festival director will bring her home to give her lectures. Meanwhile, I Will Be Cleopatra will more than compensate. On my shelf are books on theatre by Peter Brook, Kenneth Tynan, Moss Hart, Tyrone Guthrie, Jonathan Miller, and John Lahr. Zoë Caldwell now belongs in that pantheon – and there can be no greater praise. It is a great book by a great actress about a great art.

Comments powered by CComment