- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Custom Article Title: Bridget Griffen-Foley reviews 'The Murdoch Archipelago' by Bruce Page

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Rupert Murdoch certainly attracts a good class of biographer. There was George Munster, who contributed so much to Australian politics and culture by helping to establish and edit Nation, and William Shawcross, one of Britain’s most prominent journalists. There were other biographies, too, before the efforts of Bruce Page ...

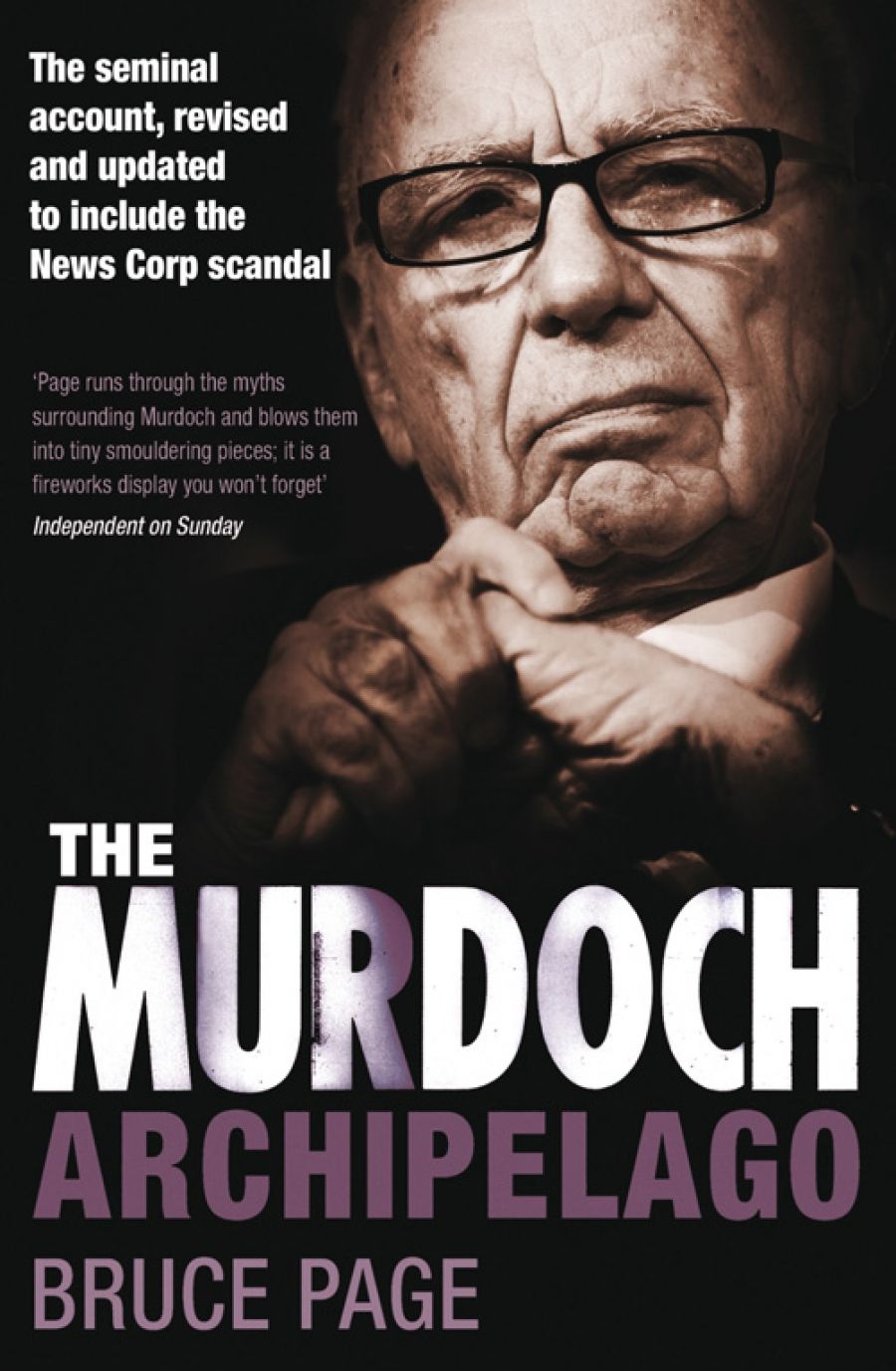

- Book 1 Title: The Murdoch Archipelago

- Book 1 Biblio: Simon & Schuster, $49.95 hb, 580 pp, 0743239369

But The Murdoch Archipelago differs in one obvious respect from most of these earlier books – it is a study rather than a biography. It is a study, in essence, of the Murdoch method and an analysis of the qualities of personality that made father and son such formidable exponents of the trade in political favours. It seeks to dissect, in one volume, News Corporation’s activities in three countries and political cultures – Australia, the US, and Britain – connected to, but quite remote from, each other. The book is also a meditation on media history and practice, and on the nature of power, and a passionate plea for the repair of the political process whereby the interlocking issues of news media regulation and administrative disclosure are addressed.

The challenges faced by earlier Murdoch biographers, and Rupert’s decision not to proceed with an autobiography, come as no surprise after reading Page’s book. He demonstrates, more insistently than any other writer, that Rupert Murdoch is ‘a poor witness’ on the history of the enterprise he controls (Kerry Packer isn’t much better on Australian Consolidated Press) and that both Murdochs have displayed a ‘lack of practical interest in disclosure’. (I could add that that’s why the ‘News Ltd Archives’ – a term that holds out such promise – are so disappointing.) That Keith Murdoch, like his son, peddled in political secrets and intrigue Page sees as completely antithetical to what journalism purports to stand for. In the early chapters of the book, the author makes a striking comparison with another important father and son, the newspaper editors Syd and Adrian Deamer. The former’s professional interest lay entirely in the day’s disclosure; whatever was on his mind reached his newspaper with virtually no delay.

It is no accident that Page uses the word ‘witness’, for The Murdoch Archipelago puts Rupert Murdoch on trial. Halfway through the book, we are treated to a list of ‘items of concern’ (read ‘indictments’) to date: from Murdoch’s removal of Rohan Rivett from the Adelaide News, and the role Murdoch and Jack McEwen played in smearing Billy McMahon in 1968, to the ‘gross’ political campaigns of 1972 and 1975 and the New York Post’s incredible ‘Son of Sam’ escapade in 1977. The most revealing and plaintive comment is tucked away in the discursive Notes: ‘Many of us wished to think well of Rupert Murdoch,’ writes Page, who began his career on the Melbourne Herald, the newspaper at the centre of the media chain run by Sir Keith.

This utterly unrelenting book points out that Keith Murdoch never created a newspaper and that News Corporation’s papers have not been involved in investigative journalism or in disclosing wrongdoing in high office; a telling case study is that of 1975, when the Melbourne Herald (at that time between Murdochs) uncovered the abuses committed by Rex Connor, the Labor cabinet minister, while The Australian simply bellowed and Murdoch informed himself behind the scenes. The Murdoch Archipelago is generally convincing, although I find it hard to believe the claim that no award has gone to a newspaper under Murdoch’s control, and I think the author is rather too negative about The Australian. For all the embarrassing problems of its début and the demise of Adrian Deamer, it overcame the considerable difficulties posed by Australian geography to survive as a national newspaper, it encouraged improvements in the coverage of politics and the arts, and, until 1975 at least, it provided something of an oasis for mentally undernourished Australian journalists.

The range of this beautifully written book is quite breathtaking, not just stretching across continents but drawing on works of philosophy, literature, psychology, and political theory. Epigraphs and lengthy digressions draw on Shakespeare and Marlowe, Machiavelli and Weber, Locke and Bacon, Judith Wright and Henry Reynolds. The Murdoch Archipelago’s discursiveness is apparent from the date range of individual chapters: the one on the Times, for example, goes back to 1819. All the while, Page is intent on establishing benchmarks (his word) against which to measure the performance of journalism and democracy under the Murdochs. Page’s summation of complex editorial and business happenings is typically sound and deft, and often ironic; the testimony of the ‘great white shark, merciless and deadly’ before the Australian Broadcasting Tribunal in 1979 is summed up as that of a man ‘promising to avert the consummation of monopoly’. Just occasionally, Page’s judgment founders – why describe John Gorton as a ‘guileless landowner’? – and the digressions seem a little self-indulgent.

Given the extraordinary breadth of Page’s reading, interviewing, and thinking, it seems churlish to record a few oversights and mistakes, but here goes: there is no mention of the precocious correspondence between a young Rupert Murdoch and Ben Chifley, discovered by Clem Lloyd a few years ago; the Australian Financial Review was launched by Jack Horsfall in 1951, not by Max Newton in 1963; Malcolm Fraser, a committed republican, does not have a knighthood; and the Australian National Library is more properly known as the National Library of Australia. The most curious omission is that of Murdoch’s third wife, Wendy Deng. While this was never intended as a conventional biography, it would have been interesting to see what significance (if any) the author attributed to Murdoch’s marrying a Chinese woman. Likewise, a book about the ‘Murdoch method’ would surely have benefited from a consideration of the grooming of Rupert Murdoch’s heirs.

Page sometimes overstates his case, but, in challenging the ‘heroic version’ of the dynasty, he argues persuasively that commercial success has not been due to the Murdochs thumbing their noses at the establishment. The reality, in fact, was pretty much the opposite, as Rupert Murdoch took advantage of the ‘charisma’ of his nationality in Britain and became a dedicated insider benefiting from political and social patronage. Page sees the ‘General Theory of Establishment’ as a key component of the Murdoch ideology and method, with News Corporation suggesting that its role is to befriend the populace everywhere against the élitist, snobbish masters of the world and to celebrate the values and interests of the workers through its tabloids.

Read this leviathan and, yes, weep.

Comments powered by CComment