- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Custom Article Title: Older than Hemingway

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Older than Hemingway

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

One of the hardest things a reviewer can be asked to do is to produce copy about a book that is so beautifully done that commentary on it seems both ridiculous and vaguely offensive. That is my predicament here. It is with a certain wry delight that I can report that this is the second time I have been in this position in recent months. The other book was a first novel, too. It is tremendously heartening to know that creative writing not merely good but of the highest order is being produced in these dismal times.

Shantaram is based on the life of its author, Gregory David Roberts. A heroin addict, Roberts was sentenced in 1978 to nineteen years’ imprisonment as punishment for a series of robberies of building society branches, credit unions and shops. In 1980 he escaped from Victoria’s maximum-security prison, thereby becoming one of Australia’s most wanted men for what turned out to be the next ten years.

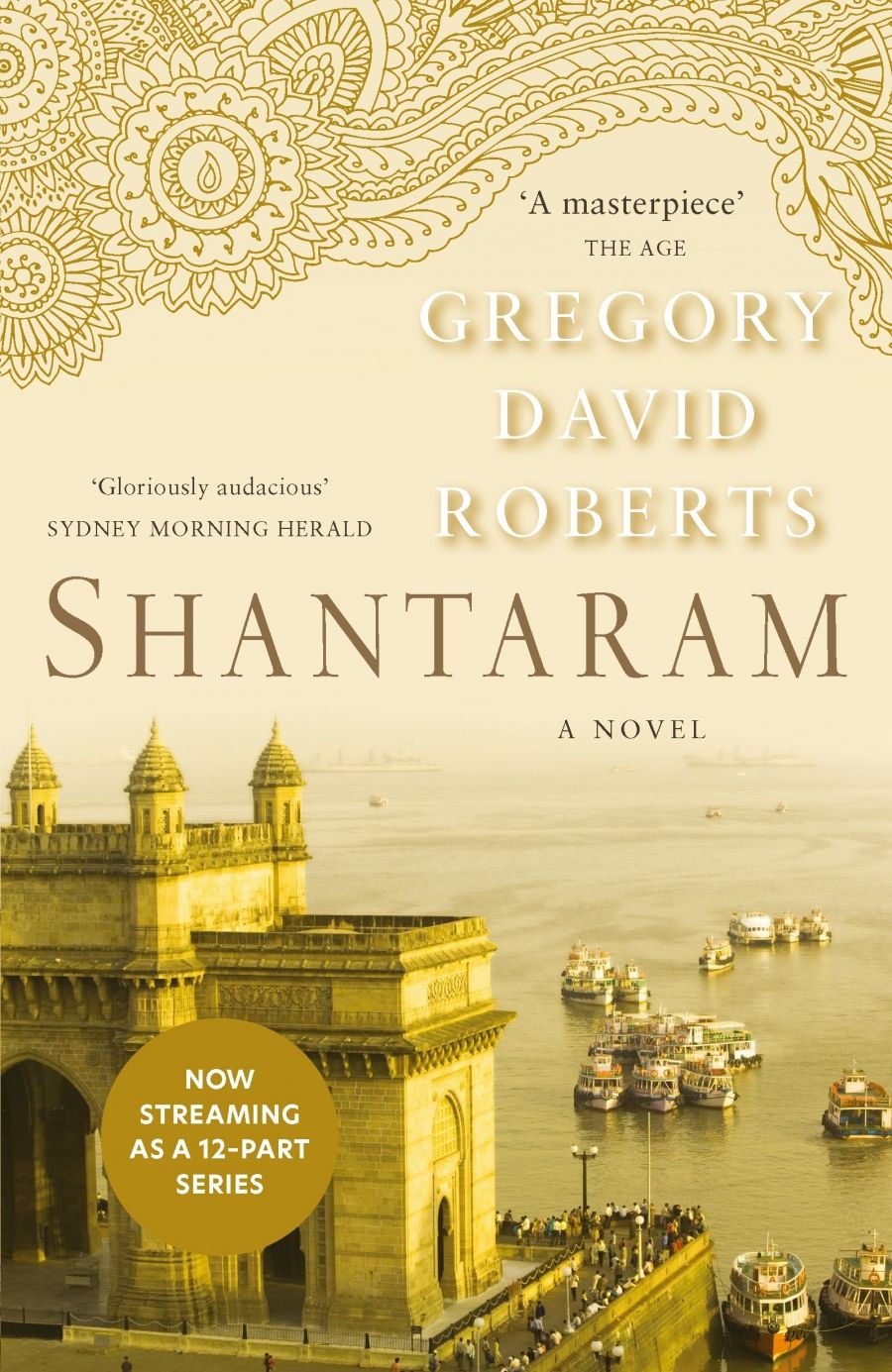

- Book 1 Title: Shantaram

- Book 1 Biblio: Scribe Publications, $49.95 hb, 936 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

After an interlude in New Zealand, he lived for most of this period in Bombay. He set up a free health clinic in the slums, acted in Bollywood movies, worked for the Bombay mafia as a forger, counterfeiter and smuggler and, as an arms dealer, resupplied a unit of Mujaheddin fighters in Afghanistan. He was captured in Germany in 1990 and eventually extradited to Australia. After completing his prison sentence, he established a small multi-media company, and is now a full-time writer.

So what can I say about his book? How can I evoke, without cliché or marketing blather, the nature of the reading experience? Let me try analogy. Although there are few similarities between the respective prose styles, Shantaram recalls Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises in the visceral immediacy of its street life. The characters and dialogue are both present and felt, which is exhilarating and terrifying by turns.(Being ‘there’ in a book is not necessarily an agreeably relaxing experience.) As Hemingway does in his best work, Roberts achieves a narrative voice that conveys honesty, sensitivity and a mass of concealed psychological lacerations. This voice, of course, is a contrivance, but it has an integrity – a literary and moral integrity – that can be described as fierce. It is, at any rate, compelling.

Unlike Hemingway, Roberts can be very funny. Didier Levy, one of the many splendidly evoked characters in Shantaram, a thirty-five year-old Frenchman of extensive subterranean knowledge and power, regrets that an acquaintance, Federico, has found religion. ‘“Fanatics,” Didier mused, ignoring the rebuke, “always seem to have the same scrubbed and staring look about them. They have the look of people who do not masturbate, but who think about it almost all the time.”’ Context is everything in a novel so, as the saying goes, ‘you had to be there’, but Shantaram flowers luxuriantly with passages of this type. Like Hemingway at his best, Roberts reveals his characters and his situations largely through the medium of dialogue.

The publisher’s website describes Shantaram, inter alia, as:

a compelling tale of a hunted man who had lost everything – his home, his family and his soul – and came to find his humanity while living at the wildest edge of experience. Nothing like this has been written before, and nobody but Greg Roberts could have written it now.

It is important that I mention this, because it is important to understand why such promotional balderdash is so nauseating. Shantaram is a great book: it is not a Hollywood mini-series.

Lin, the first-person narrator of the novel, makes friends in Bombay with Prabaker, who becomes his guide, but in more than the touristic sense. Early in the book, Prabaker takes Lin into a poor quarter of the great city. Eventually, the way becomes so narrow that the blazing light of the Indian day is quite extinguished and Lin must follow Prabaker, his feet touching either wall to avoid the excremental slime and rats, invisible in the darkness but as large and as heavy as small dogs, pressing against his legs, to a place guarded by a huge, ferocious man who strikes fear into the heart of the escaped convict. At Prabaker’s insistence, Lin speaks some words of Marathi to the man, who roars with delight and allows them entrance. In a kind of courtyard, men, some of them Arabs, are drinking black tea and talking. A group of children sit together on a long wooden bench beneath a ragged canvas awning. It is a people market: the children – ‘thin, vulnerable, and small’ – are slaves. Prabaker, explaining everything, quietly and slowly, ‘played the Virgil’.

The reference to Dante is masterly in its placement and climactic in its power. The scene is horrible, fascinating, unforgettable, and the narrator does not spare himself when describing his silence, his complicity. ‘Prabaker played the Virgil’: yes, we are in hell, and it’s not a rhetorical gesture, because Lin, the narrator, is there and knows it in the moment.

‘He was Australia’s most wanted man,’ burbles the front cover of Shantaram. ‘Now he’s written Australia’s most wanted book.’ If I have conveyed why I find such promotional blather so idiotic, this review will not have been a waste of time. A man who can write about ‘the lonely, angry longing to be loved’, a man who can describe himself as ‘shell-shocked’ in the first years after his escape, who can write, ‘No one, and nothing, could really hurt me. No one, and nothing, could make me very happy. I was tough, which is probably the saddest thing you can say about a man,’ may not have the awesome severity of Hemingway’s best prose, but is older than Hemingway ever was, and deserves more respect.

Comments powered by CComment