- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

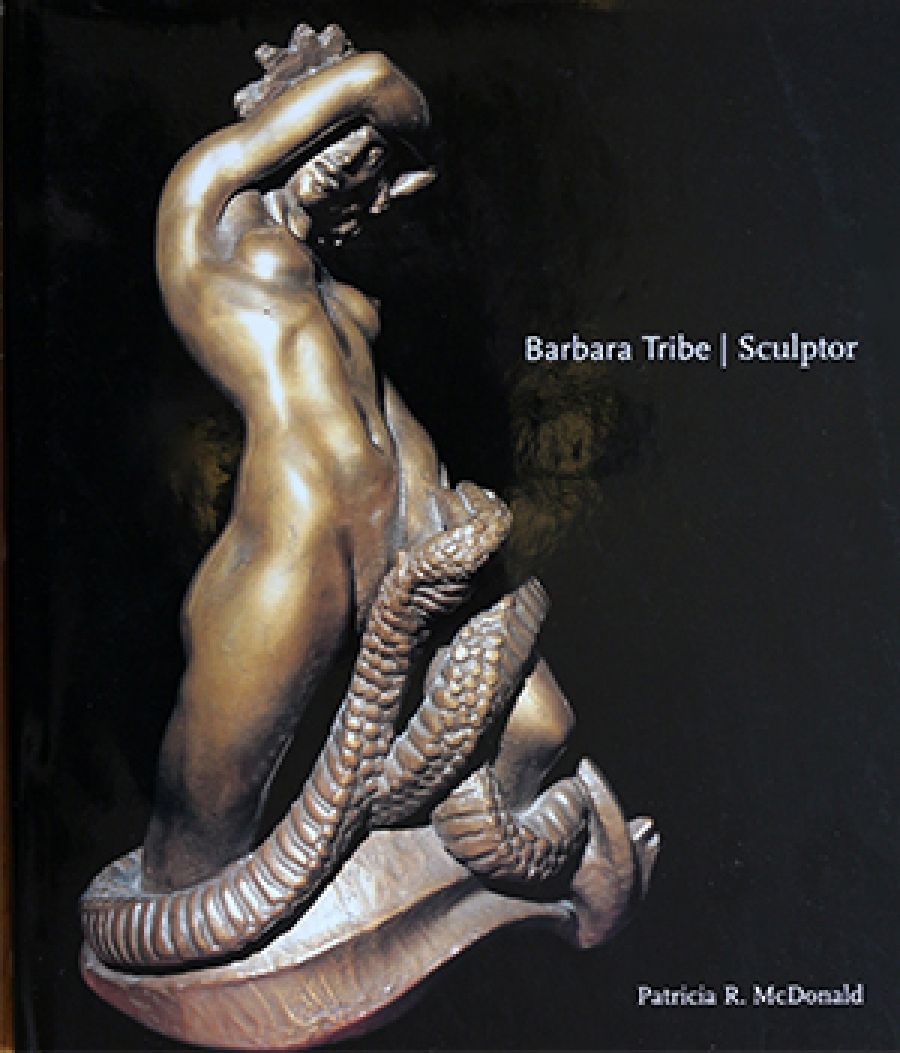

We should no longer marvel at the way art historians are forever finding yet another woman artist to rescue from undeserved obscurity. With Patricia R. McDonald’s tribute to Barbara Tribe we have the work of this eclectic Australian sculptor finally validated in a handsomely produced monograph.

How often since then and the unveiling of the Anzac Memorial in Sydney’s Hyde Park have countless thousands been moved by its artistic virility and heroic masculinity? Yet how many have realised that a significant part of this heroic statement in stone was made by a woman?

Tribe initially enrolled in the East Sydney Technical College in 1928 as a precocious fifteen-year-old and was soon singled out for praise. In 1932 she completed her diploma course under the great Raynor Hoff’s direction. Indeed, she was unquestionably his greatest protégée and for eight months she assisted him with work on the Memorial. Thereafter, she left to pursue her scholarship in England and became, for thirty years, virtually a forgotten daughter of Australia.

It is surely ironic that the welcome accolade of this art scholarship made Tribe and her work strangers in her homeland. Indeed, it was not until 1986 that a major exhibition back in Australia (and that in a regional commercial gallery) gave her countrymen an opportunity to acquaint themselves with her work.

Although the art scholarship ended in mid-1937, Tribe resourcefully found a niche with the organisation in London which was responsible for recording significant buildings and monuments at risk from wartime bombing. Ten years later, in 1948, Tribe moved to Cornwall and regionalised much of her exposure. Even so, she did manage to contribute to such prestigious venues as the Royal Academy, the Royal Society of British Artists, the Royal Society of British Sculptors, and the Royal Scottish Academy. Throughout all these years the one constant in Tribe’s work remained her fascination with the archetypal themes of creation, growth and regeneration.

However, as a salutary lesson to today’s ambitious young artists, it should be noted that it was not until 1965 that Tribe’s first works were acquired for any public collection - and that at the provincial Stoke-on-Trent Museum and Art Gallery. Perhaps this impetus as well as a succession of earlier personal tragedies encouraged her to return to Australia at last.

This return was to be the first of a series of subsequent visits and since then Tribe’s work has gradually entered the collections of Australia’s major public galleries. On one of those visits, Tribe was befriended by a Sydney patron, John Schaeffer, whose input with both finance and encouragement was instrumental in seeing this monograph published. Thereafter, Patricia McDonald’s book was launched in December 1999 at an Art Gallery of New South Wales’ exhibition commemorating the sculpture of Raynor Hoff and his school.

This superb exhibition, curated by Deborah Edwards, went some way towards contextualising Tribe’s work and clearly showed why the Travelling Art Scholarship was a deserved accolade. While McDonald’s book fails to place Tribe in any artistic context (Australian or otherwise), it does strive to compensate for this omission by ranging over a lifetime’s work which includes portrait busts, figure and animal sculptures, ceramic works, coiled pots, wood and stone carvings as well as gouaches, watercolours and drawings.

Surely, for this reason, the book and the exhibition’s own thorough catalogue should be coupled to provide a complementary coverage of this vital contribution to Australian art? Taken together they provide a long overdue assessment of the Dionysian paganism and virile sexuality which energised many in Sydney’s art community between the wars, whether they were inspired by Raynor Hoff or by Norman Lindsay.

On a purely personal level I must admit that I find much of Tribe’s work beside her bronzes distressingly redolent of the insular arts and crafts coterie she chose to inhabit in Cornwall. Perhaps unfocused rather than the kinder word’ eclectic’ would be a better description of her output?

Whatever the case and whatever the personal opinion, with McDonald’s book we can now enjoy, through superb reproduction, the eroticism of such splendid 1930s bronzes as Caprice, Medusa, and Lovers II. While taking into account how young and impressionable Tribe was at the time, others might prefer the full-blown exuberance of Dust and Deity, Bacchanalia, and Dracula from the same period. The fact that these panels were produced for theatrical decoration must temper any judgment. Even so, to me they come across as more like theatrical camp art meets Rosaleen Norton than as major works in the Australian artistic canon.

Yet again these excesses could, for some, be redeemed by the work Tribe produced away from Raynor Hoff’s overwhelming influence; her sensitive if not elegiac bronzes of children and her later powerful portrait busts including those for the Australian War Memorial as well as that of Lloyd Rees.

On another level, however, the text of this book has perhaps been overburdened by a lifetime, and a long lifetime, of documentation retained by the sculptor. For this reason it sometimes becomes a numbing barrage of names, dates, schools, associates, events, and so on, all of which concentrate on the minutiae of a career rather than contribute to a consolidating and critical overview. It is a classic case of less would be more.

So far as the book’s production and layout are concerned, while I must applaud the quality of many of the full-page plates, it must be said that their success is severely compromised by small, poorly-lit reproductions of gallery installations and studio interiors, obviously not photographed professionally. These do nothing for the text whatsoever.

In conclusion, it may well be that Tribe’s greatest accolade has been the opinion of the Vice-President of the Society of Portrait Sculptors: ‘She is like William Blake – wise, wily and·innocent.’

Comments powered by CComment