- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘I remember only peripheries, not centres,’ Michèle Drouan says in her memoir of marriage to a Jordanian and life with his family in a village near Jordan’s borders with Syria and Lebanon. Her perspective is deliberately oblique. Elegantly shaped, and or the most part gracefully written, her story bypasses the obvious cultural divisions. Political, religious, and sexual tensions are given minimal treatment. No dates are given: you would hardly know that the Gulf War comes within the book’s timespan, and when the sound of bombs is heard from across the border, someone quietly says ‘Lebanon’, and leaves it at that.

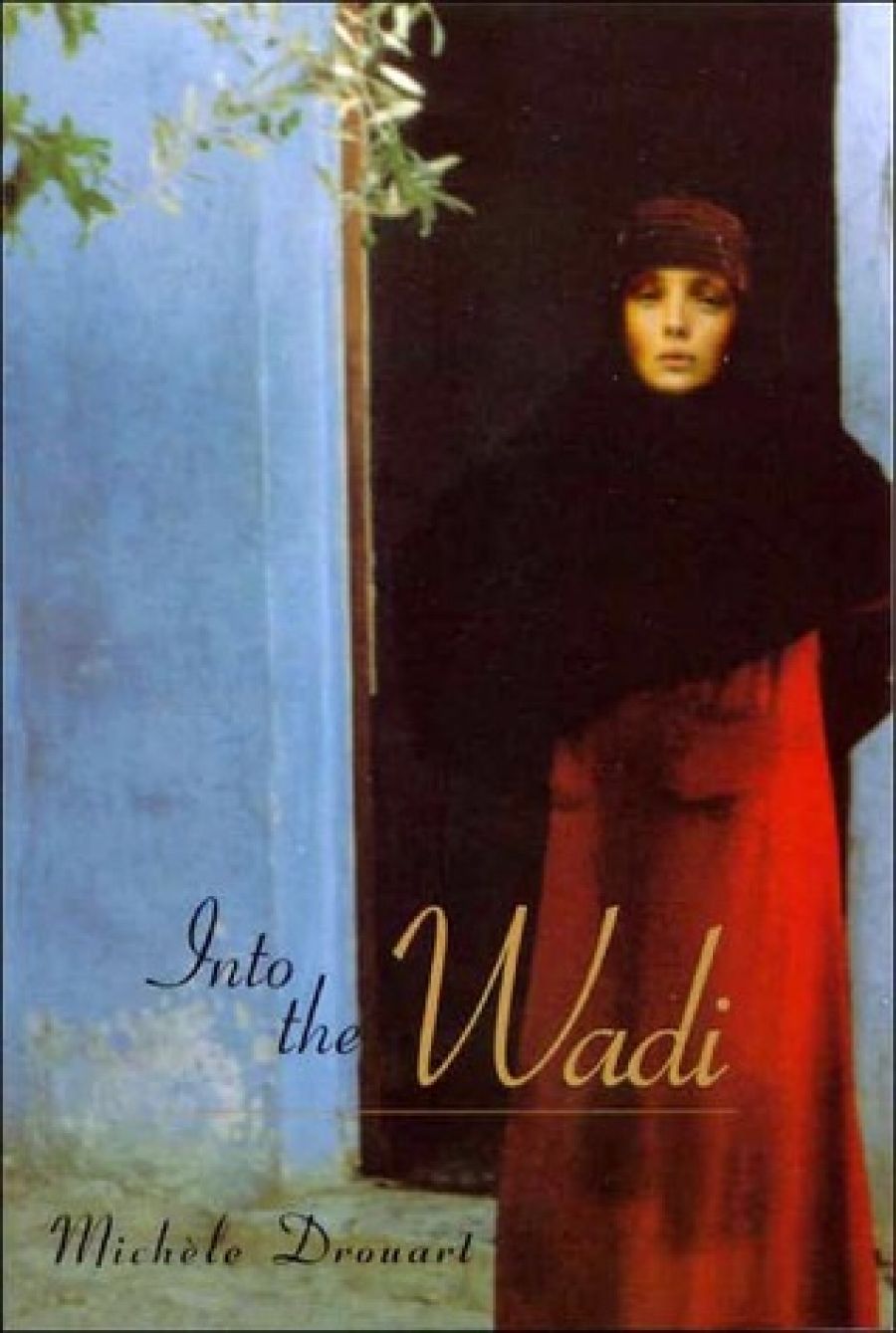

- Book 1 Title: Into the Wadi

- Book 1 Biblio: FACP, $19.95 pb, 376 pp

Australian-born, with a French father, Michèle Drouart meets a young Jordanian student in the United States and goes back with him to live with his family. She is eager to learn the language; she does her best to understand Islamic beliefs and customs and to adjust her Western ideas of a woman’s role and rights to her husband’s wishes. After some years of disappointments and estrangement, the marriage fails and she returns to Perth, where she now lives. Drouart revisits the past, not in anger, but nostalgically. She remembers that with her husband’s family she felt ‘the exultation of connectedness’. For her, that’s a key phrase. Her sense of grief seems to come not so much from the failed marriage as from the loss of connection with the village people, especially the women who welcomed her so warmly.

Compared with other Australian narratives of life within the Muslim world, Michèle Drouart’s story is gently told, in a tone of regret for a lost romantic dream. There is none of the conflict that shapes such recent popular texts as Once I was a Princess or Not Without My Daughter. Partly, of course, the lack of rancour may come from the fact that Drouart and her husband Omar had no children, no house of their own, no possessions to contest. Their marriage seems to dwindle to nothingness, with little overt expression of pain or anger. In this study of cultural contrast Drouart is writing against the grain. The vigorous give-and-take of difference which characterises Gillian Bouras’ stories of a Greek-Australian marriage are almost totally absent. Village life is a pastoral idyll. When Omar slits the throat of a ram, the ritual of slaughter is presented as a gentle, loving act.

Drouart represents her younger self as a romantic: ‘To be the other, or as close as you can come: this was the way to know the world, to be alive.’ Her father, who died when she was eighteen, was ‘a quiet and simple man without connections, and still, losing him was like dropping off the edge of the world.’ Leaving Australia for France was Drouart’s first attempt to connect with her father’s past. It’s less clear why she moved on from France to the United States. Studying at an unnamed Midwestern university, she was bored and depressed until the campus woke to an invasion of Arab students, and she met her future husband, Omar.

Omar is first glimpsed in the graduate student dining hall: a melancholy giraffe of a man, whose head gave the impression of a knob on the end of a pole. After this first visual image Drouart never quite brings Omar to life again. His mother and sisters are more strongly present, perhaps because it is their world of work that Drouart enters: washing floors, beating carpets, kneading dough. Although she is often shocked and repelled by their subservience to husbands, fathers, and brothers, she is charmed by their affection for one another, and their acceptance of her, the Westerner, as a sister and friend. There are points of friction. Drouart’s longing for privacy is seen as odd; so is her sense of personal possessions. Omar’s sisters wear her clothes without permission and are astonished that she resents it. Drouart is always disarmed by their generosity. The death of Omar’s mother is the emotional centre of her story.

The low point in the marriage comes when the young couple leave Jordan. Glasgow, where Omar does postgraduate work, is hell compared with Jordan’s demi-paradise. Seen only as a place of poverty, crowding, dirt, and exploitation, the Western city has nothing to redeem it. Indeed, the time in the West does more to destroy the marriage than the pressures of village life. Intricately structured, moving back and forward in time as Drouart remembers and reflects, Into the Wadi is memorable for its sure sense of place. It’s not surprising to find that parts of it have been read on ABC Radio, and that an extract has been published as a short story: each section has its own unity and the strengths of the book are in its evocative parts rather than its unsatisfying and sometimes sentimental whole.

Comments powered by CComment