- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

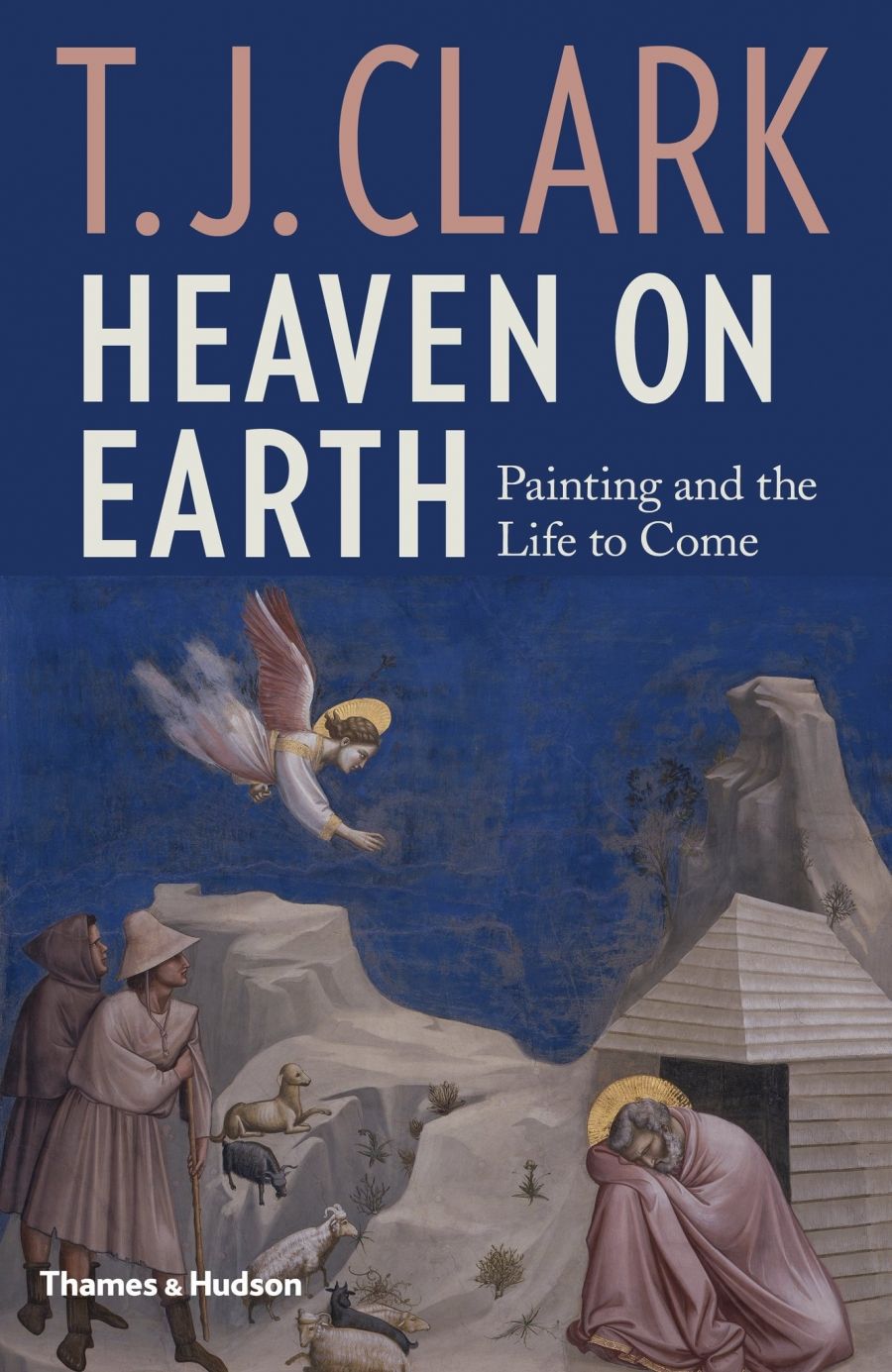

- Custom Article Title: Christopher Allen reviews <em>Heaven on Earth: Painting and the life to come</em> by T.J. Clark

- Custom Highlight Text:

Giotto’s frescoes invite us to ponder the nature of what we instinctively, conveniently, but not very satisfactorily call realism. Compared to the work of his predecessors, these images have a new kind of material presence. Bodies become solid, take on mass and volume, and occupy space ...

- Book 1 Title: Heaven on Earth

- Book 1 Subtitle: Painting and the life to come

- Book 1 Biblio: Thames & Hudson, $49.99 hb, 288 pp, 9780500021385

These appear at first to be the issues that T.J. Clark is setting out to consider in Heaven on Earth. As an art historian who has devoted most of his work to the study of the art-historical period known as ‘Realism’ – and to painters such as Courbet and Manet – he seems, on the face of it, well qualified for the task.

Unfortunately, it soon becomes apparent that the author has not really thought through the question in any depth, nor does he seek clarity and economy in the writing. The style has a kind of indulgent looseness, as though Clark believes that by slackening the reins of his prose he will allow it to run with greater freedom and spontaneity. Instead, we encounter flaccid free association, replete with qualifications and parentheses; what presumably started as a quest for the ineffable becomes vagueness, and a willingness to entertain alternative or contrary explanations becomes a tiresome mannerism:

The square is an abstraction, we might say: meaning abduction from the world of objects and events; the appeal of the absolute; ongoing distrust of ‘appearances’ whatever their earthly or heavenly guarantee; a power of generalization in human affairs that does not (cannot) know when to stop – to stop ‘turning over in the mind’.

This passage is unfortunately typical: poorly grounded in the work itself, in spite of endless inconclusive ruminations and copious illustrations, it ends up doing exactly what the author ostensibly wants to avoid, which is replacing the immediacy of experience with theoretical or ideological verbiage. It is an obstacle rather than an aid to understanding the image.

Or consider this on Bruegel’s Land of Cockaigne:

Cockaigne is a picture of gravity – the pull of a gravitational field, of pleasure as a planetary system with cooked food as its sun. Cockaigne celebrates the cooked as opposed to the raw, we could say; or, rather, the cooked replacing the raw altogether. It is a place where the founding distinction of Lévi-Strauss’ or Detienne’s ‘civilization’ has been permanently left behind. The last unconscious residues of the palaeolithic have vanished from the cultural bloodstream.

The Land of Cockaigne by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1567 (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

The Land of Cockaigne by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1567 (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

This bizarre regurgitation of cultural references sounds like something composed aloud for a dictating machine, or the excited rambling of a lecturer exhilarated by the sound of his own voice and the impression he is making on an undergraduate audience. However much pleasure it may give its author, such writing casts no light on the works it purports to discuss.

This stylistic incoherence reflects a lack of orientation in its whole conception. The theme of ‘heaven on earth’, in Clark’s hands, is far more nebulous than the outline I offered above, and it does not get any clearer as the book progresses. The substance of Giotto’s work dissolves in largely inept over-interpretation. Bruegel’s Land of Cockaigne is wrongly conceived from the outset as an example of ‘heaven on earth’, for it has nothing to do with making the transcendent concrete, and if anything it represents the weight and inertia of the body that inhibit transcendence.

Clark’s attempt at interpreting Poussin’s second Sacrament of Marriage falls foul of the obstacle that defeats so many commentators, and will always defeat those who seek to understand any one of his pictures in isolation. Poussin was a peintre-philosophe whose whole work is the record of an evolving reflection, especially on themes related to Stoic ethics and cosmology. His vision of religion, as numerous analogies make clear, is syncretistic, so that pictures on Christian subjects cannot be understood in isolation from those drawn from the Old Testament, classical mythology, and even history. But the Sacrament of Marriage is not even truly a single and independent picture. It is part of a series of seven paintings, which itself is the second iteration of an unusual subject: the Seven Sacraments. So any interpretation of this particular painting must begin with some idea of the meaning of the theme for Poussin, the differences between his two series – painted for two close friends and patrons – and the reasons for these differences. Ultimately, we must return to the question of how this set of quintessentially Christian subjects fits into Poussin’s oeuvre as a whole.

Instead, we are faced with the same drift of impressionistic musings that is all the more disappointing because the author clearly likes Poussin’s paintings. He looks closely at details, but he doesn’t see their significance. It is the same problem we encounter in the other chapters, of attempting to interpret as mimetic or psychological phenomena what are really instances of coded and iconographic meaning, in the same way that those who don’t understand a foreign language take metaphors and idioms literally.

The book feels like a veteran art historian’s attempt to cut loose from scholarship and his field of specialisation, and to venture into a broader and more speculative, even philosophical kind of reflection. Unfortunately, the approach is mismatched with the material, and the result is a book that not only fails to illuminate but actually obfuscates its subject.

Comments powered by CComment