- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Custom Article Title: Geoff Page reviews <em>The Tomb of the Unknown Artist</em> by Andy Kissane

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Andy Kissane, who (with Belle Ling) shared the 2019 Peter Porter Poetry Prize, is one of Australia’s most moving poets. He is unfailingly empathetic, a master of poetic narrative – and of the ‘middle style’ where language is not an end in itself but an unobtrusive vehicle for poignancy (or, occasionally, humour or irony). The Tomb of the Unknown Artist ...

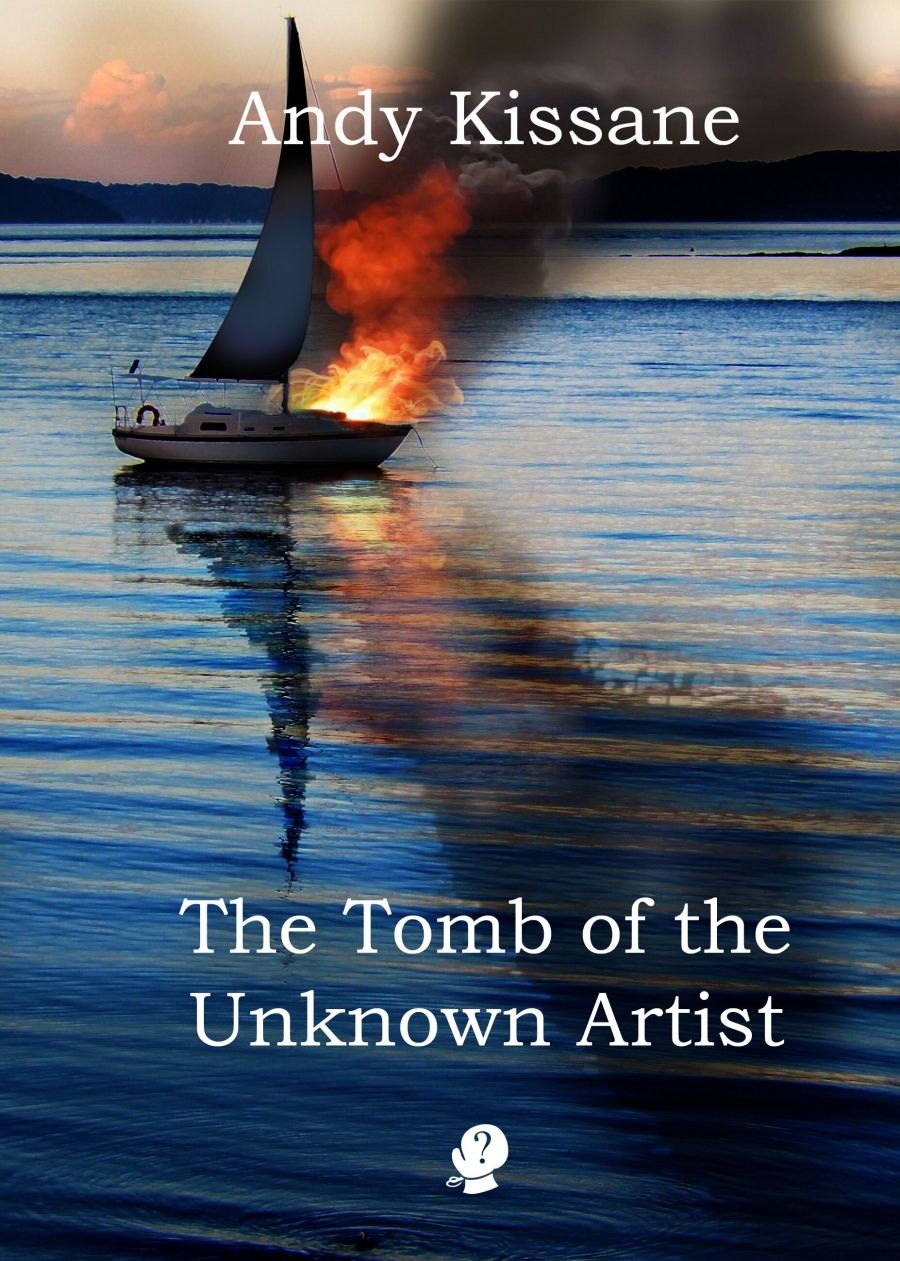

- Book 1 Title: The Tomb of the Unknown Artist

- Book 1 Biblio: Puncher & Wattmann, $25 pb, 88 pp, 9781925780376

A few of the poems in Part Two, such as ‘Getting Away With It’ (about how much one poet must inevitably owe so many others), are light-hearted, but several others are what one might loosely call ‘protest poems’. They include ‘Modern Whaling’, ‘A Wall of Eyes’ (a child’s monologue about Dr Josef Mengele, set in Auschwitz), ‘After the Deluge’ (set in post-‘Shock and Awe’ Iraq), and ‘Shooting Footage’, about a father in a primary school who initially ‘films [his] daughter // and her friends playing hopscotch’ and then films the boys who are ‘dragging Joshua towards the Disabled Toilet’, carrying him ‘like a trussed pig’. It’s a sickening exposé of the bullying that continues in our schools.

The only occasion where Kissane’s touch is less than certain occurs in this section, namely in ‘Beached Dreams’, based on Slessor’s ‘Beach Burial’. It’s an ironic and strongly felt pastiche that attempts to come to address a major national shame, i.e. the continuing incarceration of innocent asylum seekers on Manus Island and Nauru. Even its best stanza, however, has an awkwardness that never troubled Slessor. ‘Between the fob and mincing of the sound bite, / no one, it seems, has time for this – / to pluck them from a watery grave, wrap them in blankets / and raise a glass to honour // their remarkable courage ...’ Slessor’s subtle half-rhymes are not the only thing missing here.

Part Three, by contrast, is the most powerful of The Tomb of the Unknown Artist. It’s a series of monologues spoken by an infantryman in the Vietnam War. Kissane himself is too young to have served in that war himself. Unfortunately perhaps, he doesn’t acknowledge the accounts that must have underpinned his unbearably graphic recreation of it. All ten poems are of the same high quality, and most detail episodes that would almost certainly have caused their narrator, not to mention the Vietnamese soldiers, villagers, and children he encountered, some kind of PTSD later. One poem, ‘The Firefight’, addressing the PTSD issue directly, ends with: ‘in your dream / you are stricken, petrified, legless – / unable to run or crawl or do anything / to escape the barrage raining down / on you, night after sleepless night’.

The most affecting poem would have to be ‘Searching the Dead’ (which won the Porter Prize), though ‘The Book of Screams’ is even more horrifying. In ‘Searching the Dead’, the narrator is sent out ‘to search the pockets of the dead’ for ‘intelligence’ and finds only things that remind him of the humanity of his enemy. Items such as: ‘A cowrie shell bringing news of the South China Sea. / In one man’s pockets a pair of lacy black knickers. / And photos wrapped in plastic to preserve them – a girlfriend leaning against a motorbike, a couple posing / near a lake, a family in front of a shimmering pagoda.’

After all this intensity, Part Four risks being anti-climactic but nevertheless remains a convincing meditation on various aesthetic issues – often, but not always, through the eyes of an unnamed painter. Among them is the bitterly satirical title poem. Even more memorable is the group monologue ‘Degas’s Women’. Each of its stanzas starts with a new assertion: ‘There are so many / of us and we are beautiful.’ ‘We are Degas’s nudes / and we are washing.’ ‘We are rarely identified, / seldom named.’ ‘We are turned away / so you may never glimpse / our faces.’

The poem is both a critique and a celebration. It avoids dismissing the artist’s ‘male gaze’ as being merely exploitative while, at the same time, conceding implicitly that the fact of the women speaking collectively (and anonymously) is a statement in itself. It’s an entirely typical Kissanean subtlety.

Comments powered by CComment