- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Cultural Studies

- Custom Article Title: Writing from the roots

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Writing from the roots

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

This book is dedicated to all Asian Australians. Like the term ‘Chinese Australian’, ‘Asian Australian’ is revealing to my baby-boomer generation of Australian-born Chinese, for we have lived most of our lives known as Australian Chinese, a term that stresses our ethnic background over our Australian birthplace, even though our families have contributed to Australia for four, five or six generations. We may not speak a word of our ancestral tongue, and may never have trod the land of our forebears. The new term recognises that the growing numbers of Australians of Cambodian, Chinese, Indian, Korean, Malay, Thai, Vietnamese and other Asian heritage are equally Australian as are white Anglo-Celtic Australians.

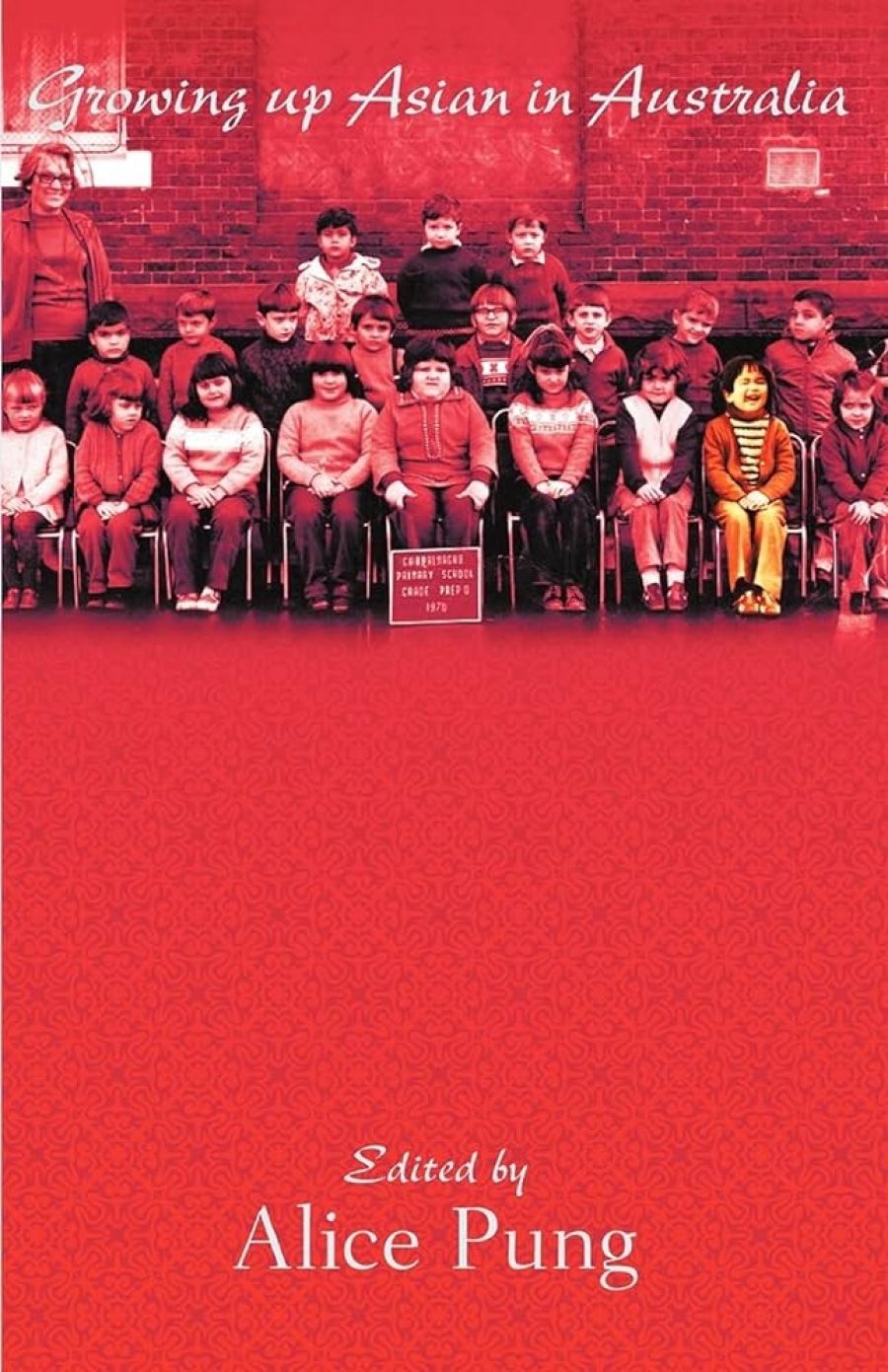

- Book 1 Title: Growing Up Asian in Australia

- Book 1 Biblio: Black Inc., $27.95 pb, 360 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

These new voices are riding on the success of Alice Pung, the young Melbourne lawyer whose Unpolished Gem (2006) shone with its originality and wry humour. Helen Garner launched this memoir by the unknown daughter of Chinese-Cambodian boatpeople who fled the horrors of Pol Pot’s Killing Fields for working-class Footscray. Its success prompted Black Inc. to commission this anthology, with Pung as editor.

She structures the book in ten sections – ‘Strine’, ‘Pioneers’, ‘Battlers’, ‘Mates’, ‘The Folks’, ‘The Clan’, ‘Legends’, ‘The Hots’, ‘UnAustralian?’ and ‘Homecoming’ – each of which has four to seven authors who ‘show us what it is like behind the stereotypes’ of Asian Australians. As Pung says in the introduction: ‘They are not distant observers, plucking the more garish fruit from the lowest-hanging branches of an exotic cultural tree. [They] are the tree, and they write from its roots.’

In another section, ‘Tall Poppies’, Pung selects nine high-profile figures, including film director Khoa Do (Young Australian of the Year 2005), lawyer and republican campaigner Jason Yat-Sen Li, former television Playschool presenter Joy Hopwood, and Triple J’s Caroline Tran, who reveal themselves through answers to a set of questions.

The underlying theme is coping with difference: the search for identity; ambiguity towards the motherland and language of the ancestors; longing for normality, childhood embarrassment, if not shame, at parents’ behaviour in front of other children; and generational and cultural clash. Although the difference explored is that experienced by Asians in a predominantly Anglo-Celtic country, non-Asian readers will also relate to much of the content, as most children, be they freckled, red-haired, skinny or dumpy, feel a degree of difference from their peers. Sunil Badami hates his name: ‘It’s too hard to say. It’s too – it’s too Indian!’ he explodes to his mother. His words, ‘I just wanted to fit in’, express the wish of almost every child, white or non-white.

Even in multicultural Australia, some overt racism outlives the buried White Australia policy. ‘Do you speak English?’ ‘Did you come here by boat?’ ‘Do you eat dogs?’ ‘Do you wipe your arse?’ ‘Ching-chong Chinaman!’ Geelong boys pelt fourteen-year-old Simon Tong, ‘the new animal at the zoo’, fresh from British Hong Kong in the 1980s. In Canberra, when six-year-old Aditi Gouvernel’s left hand brushes against a schoolboy, he rips off his shirt, tosses it away and yells, ‘You’re Indian and I’ve got your Indian shit on me’.

Prejudice isn’t confined to the white camp. Lazaroo, in a moving story of her Eurasian father’s death in Perth, recalls his Singapore family’s objection to his marriage with a white woman. ‘Don’t fool around with Aussie girls,’ teenager Francis Lee’s parents warn as he sets sail for an ‘Upside-Down Year’. As well-heeled Aunt Yee Mah explains to Vanessa Woods in her beautifully observed ‘Perfect Chinese Children’, her mother is poor because she married a gweilo (foreign devil). ‘Chinese were using chopsticks while gweilos were eating with their hands.’

Many of the contributors grow up in crowded conditions attached to fruit or video shops, restaurants or cafés. Some youngsters, such as Diem Vo in Footscray, act as their parents’ interpreter, forging their signatures, writing their own sick-leave certificates. Others, such as Ray Wing-Lum, accompanying his father as he delivers fruit and vegetables, are amazed by Sydney’s leafy North Shore, where people live in houses like the ones on television. But at school he walks ‘the playground in the middle of a thousand boys, invisible and absolutely alone’.

Ambiguity is felt by a majority of Asian Australians. At school, Jacqui Larkin’s black hair makes her stand out ‘like a plate of chicken feet at a sausage sizzle’, and she longs to ditch her fried rice and mini spring rolls for Vegemite or peanut butter sandwiches. While in Hong Kong, Larkin is cut off by the alien, Cantonese tongue; in Beijing, Leanne Hall finds herself ‘at home’, despite being unable to speak a word of Chinese. Sim Shen, who moved to Adelaide when thirteen, discovers on a visit to Hanoi ‘the place I was “returning” to was not a real place any more – it belonged to the past’.

So many segments tug at me that I can’t mention them all. Lian Low laments that, with her mix of Malaysian-lilt, Manglish, television-influenced Americanisms, the Queen’s English and Australian, ‘My attempts to blend in failed as soon as I opened my mouth’. With delicacy and delight, Shun Wah records life on a Queensland poultry farm, where spiders come ‘abseiling down like US commandos’. Kee, in a taut extract from A Big Life (2006), finds being Asian an asset: ‘Boys, I learnt, found “exotic” girls “sexy” ... I was going to go out and get it all.’ Kwong, paying homage at her ancestral shrine in Toishan, rummages around and fortunately finds a mint ‘to add sweetness to the afterlife’. Dubbed a ‘fucking poofter’, Ayres blows a kiss to a skinhead. And Cindy Pan, in ‘Dancing Lessons’, fantasises over Shanghai-born Margot Fonteyn.

The pages I find most painful are by Vietnamese Australians who fail their newly arrived families’ expectations. Diana Nguyen disappoints her mother by taking to the stage, rather than to medicine, and is thrown out of home for losing her virginity. She’s reduced to a ‘slut daughter’. Pauline Nguyen (not related), in a powerful excerpt from Secrets of the Red Lantern (2007), records brutal beatings by her father whenever she scores less than an A-grade at school. ‘My father fled Vietnam to escape the oppression of the communist regime ... [I] in turn have had to escape the tyranny of his rule to find freedom.’

Pung’s criteria for selecting authors isn’t clear. Did she and/or the publisher invite contributions, or did writers volunteer material? It is likely to have been a combination of both. It is extraordinary, however, that, while restaurateur and Melbourne Lord Mayor John So features under ‘Tall Poppies’, Brian Castro, the award-winning author and arguably the country’s foremost novelist of Asian heritage, who landed, like So from Hong Kong, as a student in his mid-teens, appears neither as a ‘tall poppy’ nor as a writer.

Similarly, the stories and notes don’t always indicate the author’s Australian home. It is odd that, given such a comprehensive book, both the Northern Territory and Tasmania seem to have slipped off this engaging memoirist map of growing up Down Under.

Comments powered by CComment