- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Custom Article Title: Tiger luck

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Tiger luck

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

When journalist Helene Chung grew up in Hobart in the 1960s, there were fewer than one hundred Chinese living there, and her complicated family seemed to include almost all of them. Her great-grandfather came to Australia for gold, but succumbed to opium. He was rescued by her grandfather, who worked in the Tasmanian tin mines, founding a small dynasty as brothers and cousins arrived with their multiple wives, and married more in Australia. It sounds like a familiar story, but as it unfolds the author’s intelligence and determination create an idiosyncratic portrait of what first- and second-generation migrants endure, and how they triumph.

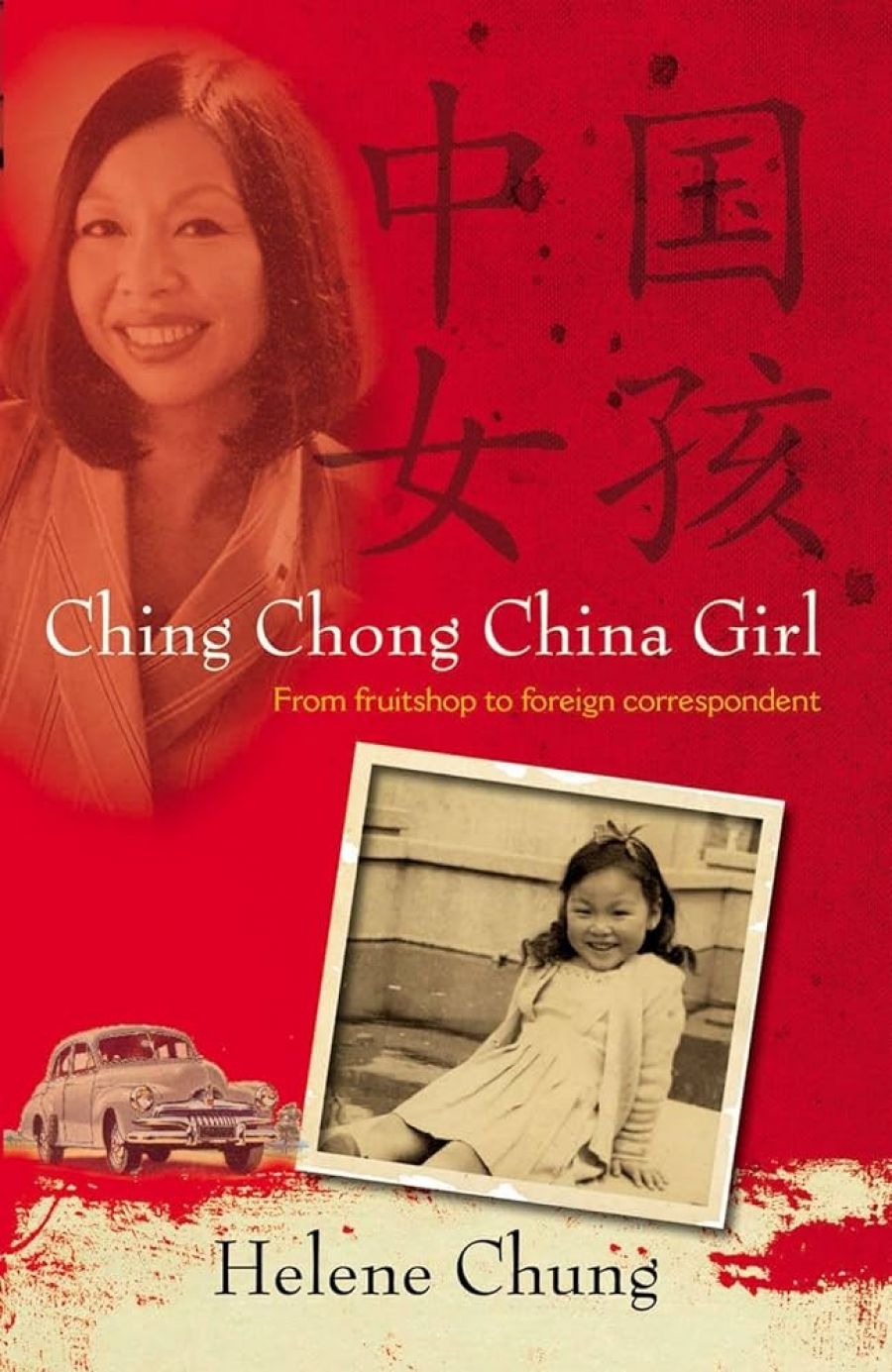

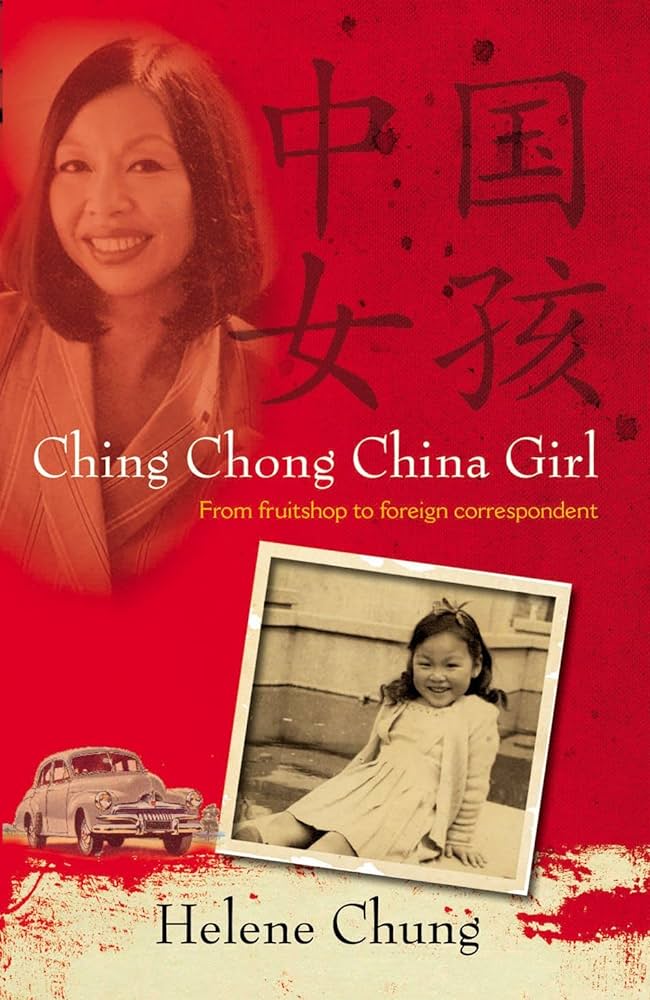

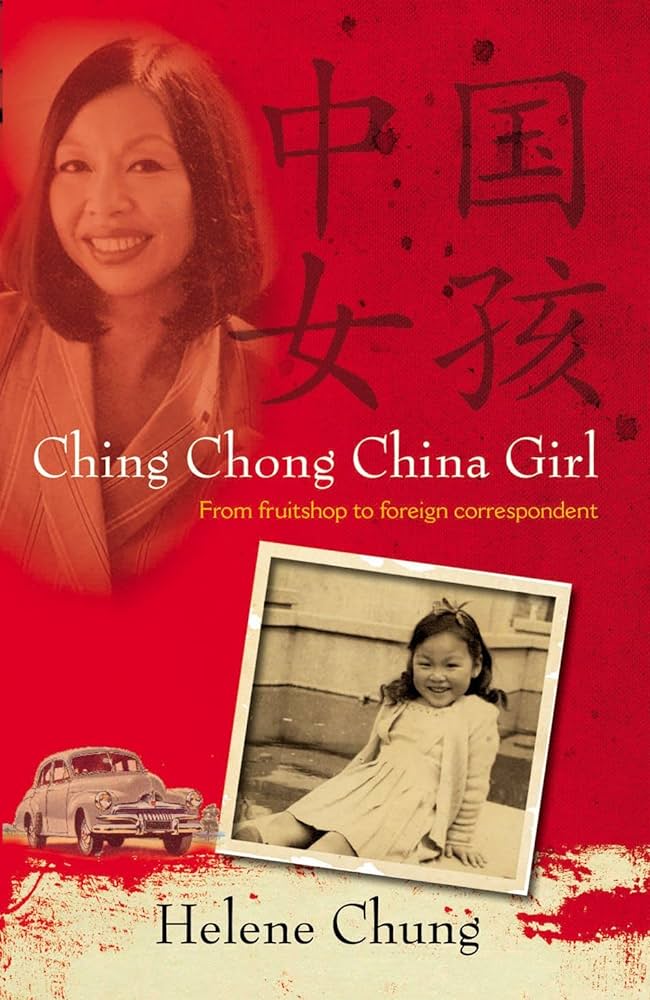

- Book 1 Title: Ching Chong China Girl

- Book 1 Subtitle: From fruit shop to foreign correspondent

- Book 1 Biblio: ABC Books, $32.95 pb, 358 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

As children, Helene and her sister lived with uncles and cousins while their mother, Dorothy, worked in relatives’ shops or earned money modelling nude for life classes at art schools in Hobart and Melbourne. She was making up for a grim childhood with a mother who insisted that, as a girl, she should have been drowned at birth. Not only was she a divorcée, shocking in Hobart then, but she played the violin, and drove a red MG with two German shepherds on the back seat.

The girls also lived periodically with some of Dorothy’s boyfriends, the most influential being Rex Walden, a radio announcer who introduced Helene to poetry recordings and arranged an ABC audition when she was thirteen. When they moved into the home of Leslie Greener, a radio journalist and architectural artist who worked periodically in Luxor for the University of Chicago, Rex came too. From this ménage à trois, the two girls left each day for their convent school.

At St Mary’s, they were the only Chinese children for most of their school years, jeered at in the schoolyard as ‘Ching Chong Chinaman’: ‘even though I yelled back “white trash!” it hurt.’ The nuns were strict, sometimes even strapping the cat, in case he was ‘the devil in disguise’, and the girls were filled with fears of sin, guilt and hell, and how much the nuns knew about the details of their life. Helene says she coped with ‘our abnormality’ by ignoring it, but, noting her obsession with personal order – all clothes hung a certain way, all books facing the same direction – she wonders whether this was ‘an unconscious attempt at symmetry in a life otherwise reeking of irregularity’.

Somehow, she studied, socialised and read loving letters from her mother, now with Greener in Egypt, about how sixteen-year-old girls should behave. Enrolling for an Arts degree (she wrote her honours thesis on anti-Semitism in England 1890–1905), she embraced student theatre and taught at her old school, despite warnings that pupils would not want to learn English from a Chinese. She was shown where the tape recorder button was for her first freelance job at the ABC, and sent off to interview a butcher who claimed to have seen a Tasmanian tiger. This experience of ‘tiger luck’, as she calls it, addicted her to ‘the adrenalin of broadcast journalism’.

After that, it is a story of travel, adventure, relationships and interviewing in Europe and Asia by a stylish young woman with a sense of humour and a complex enjoyment of life’s pleasures (the index contains forty-five references to ‘food and beverages’), as well as a keen ear for the quote that reveals the truth behind the politics. In the 1970s she reported from Singapore, Hong Kong (‘a hedonist’s heaven’) and London, where she made news by being the first person to interview Princess Anne on radio.

Back in Australia she started on AM, was the first woman to compère Correspondents’ Report and then became television’s first ‘non-white’ face on This Day Tonight. When an ABC executive told her she had no future in television because she looked Chinese, and to stop wearing make-up which accentuated her eyes, the resultant union-backed storm ended with an intervention by Al Grasby, a backdown by the ABC and a permanent position on Nationwide, leading the way for SBS’s George Donikian and Lee Lin Chin in the 1980s.

Helene’s highest profile posting was to China, where she was the ABC’s first female foreign correspondent (Shouting from China, 1988). Her Western dress and inability to speak Chinese confounded the general public, recalling her first visit to Singapore, where she ‘wondered what it was like to be Chinese’.

The end of the book is darkened by the death from cancer in 1993 of her husband, John Martin, a tragedy that she grappled with by publishing an intimate memoir, Gentle John: My Love My Loss (1995) and a book, Lazy Man in China (2004), written after her resignation from the ABC in 1998.

Ching Chong China Girl is a lively read, and a significant reminder of one of the oldest strands of the Australian migrant story.

Comments powered by CComment