- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

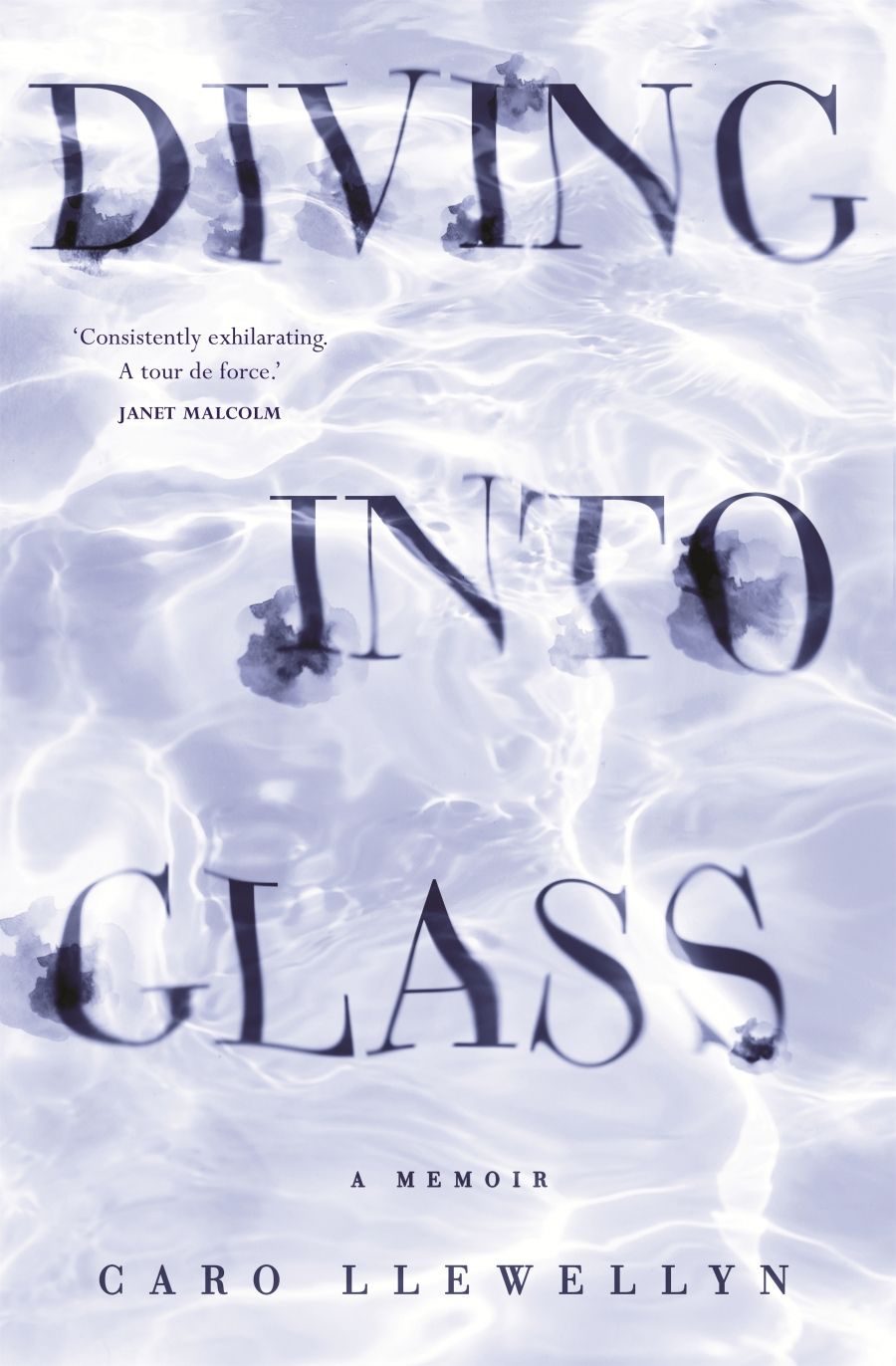

- Custom Article Title: Astrid Edwards reviews <em>Diving into Glass: A memoir</em> by Caro Llewellyn

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Memoirs of illness are tricky. The raw material is often compelling: dramatic symptoms, embarrassing public moments, and unavoidable relationship pressures. The challenge is to share that raw material in a new way. Not every memoir needs to turn on the conceit that illness is an obstacle that must be overcome ...

- Book 1 Title: Diving into Glass: A memoir

- Book 1 Biblio: Hamish Hamilton, $32.99 pb, 336 pp, 9780143793786

Llewellyn opens with quotes from Joan Didion. Didion is the most famous writer to live with multiple sclerosis, though she has chosen to stay silent on the disease for decades. Llewellyn is not silent, but aside from the prologue, where Llewellyn shares her experience of her first relapse and subsequent diagnosis, MS is barely mentioned until Chapter Thirty-Seven.

While the work is marketed as a memoir of Llewellyn’s experience of MS, in reality it is a reflection on her experience growing up with her father Richard’s severe disability. We are given a first-hand tour of what it was like for a healthy young man to contract polio in the 1960s in Australia, a time before equality and accessibility became something we talk about.

Diving into Glass is a work about a father and daughter, two individuals with experience of illness and disability. She writes, ‘my body – from the outside at least – still looked more or less like it always had. My father’s body, on the other hand, inside and out, showed every sign of the massacre that besieged him.’ Her father’s experience made a lifelong impression on Llewellyn. She recalls her father’s grace and dignity when confronting stigma and discrimination, as well as the pressures his disability brought into his relationships and the way his disability impacted his physical ability to parent unruly children.

It is also a work recounting Llewellyn’s impressive arts career. How many people can count Salman Rushdie as a former boss and the late Philip Roth as a friend? It is also a nod to her future goals. Llewellyn is by no means done making her mark.

Above: Caro Llewellyn with Salmon Rushdie at a PEN World Voice Festival in 2010. Below: Caro Llewellyn with Philip Roth on the 'Philip Roth Newark' bus tour

Above: Caro Llewellyn with Salmon Rushdie at a PEN World Voice Festival in 2010. Below: Caro Llewellyn with Philip Roth on the 'Philip Roth Newark' bus tour

This is not a literary exploration of illness in the manner of Fiona Wright’s Small Acts of Disappearance (2015) and The World Was Whole (2018). But it is a memoir of disease – both Llewellyn’s MS and her father’s polio and subsequent disability.

Diving into Glass is a reflection on disability and how we as a society have changed – and not changed – in our attitudes towards what makes a good life. Llewellyn does not shy away from sharing instances of stigma and shame about her father’s disability in her own family (especially her maternal grandmother). The work is also a reflection on the relationship between parent and child. Llewellyn often recounts the ingenious (and not always successful) means her father developed to discipline and protect his children, even though he could not raise his hands or manoeuvre his own wheelchair.

Memoirs teach us about the world and force us to consider how we would react if we found ourselves in different circumstances. They are a way to share the human experience, and to experience what is beyond our own lives. But Diving into Glass is more biography than memoir. The majority of the work is devoted to Richard Llewellyn’s life and the impact he had on his daughter. Much of the rest is devoted to her career, with her experience of multiple sclerosis bookending the work.

At several points in Diving into Glass, the language is troubling. Llewellyn refers to her father’s illness and disability as a ‘tragedy’ (as does the blurb). I’m not convinced anyone – even a daughter – should refer to another’s situation as a tragedy. But my reading of Diving into Glass is influenced by my own experience. Others, perhaps other citizens of sickness, may react differently.

This is a work for those interested in exploring life with disability, as well as how the discussion of ableism and discrimination in Australian society has evolved, in most cases for the better. It is also a work for those interested in a career in the arts, for Llewellyn has world-class tales to tell.

Comments powered by CComment