- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Religion

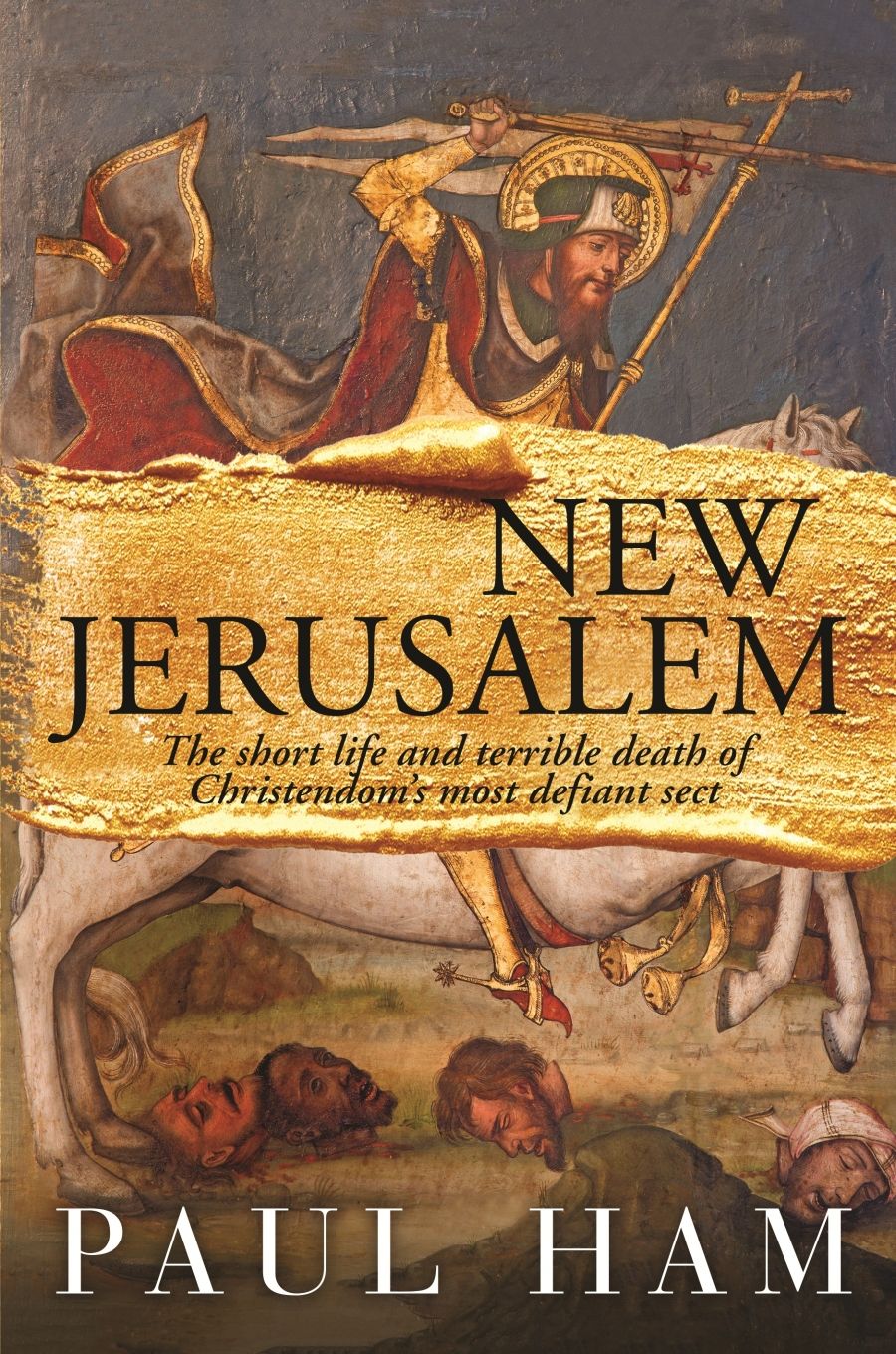

- Custom Article Title: Paul Collins reviews <em>New Jerusalem</em> by Paul Ham

- Custom Highlight Text:

The link between fundamentalist religion, violence, and madness is well established. The conviction of absolute truth becomes especially toxic when believers are convinced that the end of the world is nigh. This is exacerbated in times of major socio-economic change and political instability, such as during the Protestant Reformation ...

- Book 1 Title: New Jerusalem

- Book 1 Biblio: William Heinemann, $45 hb, 375 pp, 9780143781332

Portrait of John Bockelson, 'King John' of Leiden', as King of Münster by Heinrich Aldegrever, shortly before his execution, 1536 (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)Often in such situations, opportunists seize control. In Münster it was an astute, sociopathic Dutchman, John Bockelson, ‘King John’ of Leiden. As king of the ‘New Jerusalem’, he was to rule the world until the second coming of Christ. However, his kingdom was always small. When he seized power in the city, there were only about nine thousand people in Münster, including five thousand women, two thousand children, and about sixteen hundred combat-capable men.

Portrait of John Bockelson, 'King John' of Leiden', as King of Münster by Heinrich Aldegrever, shortly before his execution, 1536 (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)Often in such situations, opportunists seize control. In Münster it was an astute, sociopathic Dutchman, John Bockelson, ‘King John’ of Leiden. As king of the ‘New Jerusalem’, he was to rule the world until the second coming of Christ. However, his kingdom was always small. When he seized power in the city, there were only about nine thousand people in Münster, including five thousand women, two thousand children, and about sixteen hundred combat-capable men.

Drawing on apocalyptical literature, the Anabaptists believed that the end of the world was approaching. They repudiated Catholicism and Lutheranism, believed in adult baptism, and called for a radical, almost communistic sharing of goods and possessions as described in the Acts of the Apostles. Believers must be prepared to fight the ‘godless’ to prepare for the end times. All books were to be burned except the Bible. To increase fertility, male believers should have multiple wives who must submit to their husbands’ sexual demands.

Despite this, many women were attracted to Anabaptism because it gave them a sense of spiritual liberation. This can probably be traced back to the late Middle Ages when many nuns and laywomen – like Julian of Norwich, Margery Kempe, and later Tereza of Avila – found agency through commitment to a deeply personal spirituality leading them to exercise considerable influence in the church.

Ham, drawing on fascinating primary sources, tells the Münster story brilliantly. He clearly outlines Anabaptist beliefs and explains why Catholics and Lutherans held them in such contempt, seeing them as ‘barely literate zealots and crazed heretics’, lower-class nobodies who ‘proclaimed that the whole of Christendom had erred for more than a thousand years’. Luther particularly felt compromised by Anabaptism because he was primarily responsible for ‘the confusion and fragmentation’ incited by his 1517 revolt against the papacy and his attempt to reform Catholicism.

Reading New Jerusalem, it struck me that perhaps the medieval church was right in restricting access to the Bible. Anabaptists are a good example of what can happen when everyone becomes their own biblical interpreter, especially of apocalyptic books like Daniel and Revelation and prophets like Ezekiel. This is coded, symbolic, poetic literature written for times of persecution, literature aiming to provide hope for oppressed Jews and Christians by emphasising that the powers that struggle against them will be finally routed in the end times by God. Taken out of context, apocalyptic texts are open to all types of bizarre interpretations. That is precisely what the Münster Anabaptists did: wrench the texts out of their context to give them meanings that suited their purposes.

Münster fundamentalism was essentially religion gone mad, an assault on reason, and a distortion of mainstream Christianity’s attempt to hold faith and reason together, fides quaerens intellectum, faith seeking to ground itself in understanding and human experience, as philosopher–archbishop Anselm of Canterbury said in the eleventh century.

The core issue of Anabaptism is adult baptism. They argued that in the New Testament and the early church all converts were adults because conversion required a mature commitment to faith. Infants couldn’t make this commitment. In fact, the earliest unequivocal reference to infant baptism comes from the third century. However, since then it’s been a constant part of Christian tradition. Infant baptism was reinforced by Saint Augustine’s pessimistic and literal theology of so-called ‘original sin’ and of the need for baptism to counter that. The term was never used in the New Testament or by Saint Paul, who talked more about humankind’s vulnerability, weakness, and inclination to selfishness.

The end of the kingdom was terrible as the siege tightened, Münster descended into starvation, and King John into ever-deeper madness. The Lutheranleaning Prince-Bishop of Münster, Franz von Waldeck, was consumed with the desire for revenge, having been humiliated by his failure to stamp out the sect. There was to be no Christian forgiveness here. Many of the townspeople were slaughtered, and King John and the other leaders were executed with exquisite cruelty, having challenged the foundations of church and social order.

The sect, however, survived through the efforts of the gentle former priest, Menno Simons, who led the extremist Anabaptists out of millennialist madness and violence into a mainstream, moderate, almost-pacifist group, the Mennonites, the remote forerunners of today’s Baptist Church.

But Anabaptist Münster was the symbol of what was to come. It is not that peace-loving people had not tried to preach tolerance. Luther’s humanist disciple Philip Melanchthon and the Venetian Cardinal Gasparo Contarini had tried to build bridges, but in the end the hardheads were determined to fight, leading to the madness of the religious wars as Lutherans and Catholics fought each other until the Peace of Westphalia (1648). Twenty per cent of the German population was killed in the process.

Comments powered by CComment