- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Shoals of Fingerlings

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

An invaluable testing ground, the pamphlet provides emerging poets with their first real opportunity to gauge critical response prior to the publication of first collections. For readers, it brings continuity to work that, in all likelihood, has appeared haphazardly in newspapers and magazines.

The most widely published of the poets here, Louise Oxley, in Compound Eye (Five Islands Press, $9.95pb, 32pp), is also the most assured. The strength of her poetry lies in its seamless conflation of emotional experience with details from the natural world. In the opening poem, ‘Night, Connelly’s Marsh’, Oxley finds herself on a pier contemplating failed love and separation: ‘your letters have become / mere shoals of fingerlings’; and, in ‘Greek Roots’, the couple is ‘[s]tonewalled in the garden / [they] have left behind’. Oxley takes solace in memories of childhood summers spent gathering windfall apples or searching the beach for the paper nautilus (‘a seaworn lexicon’). Like many poets, she attaches importance to names, referring twice to the novelty of being a ‘mother’. Indeed, Oxley’s own names for things are often memorable. There is the plover’s cry, which ‘springs / like blood along a scratch’ and a description of her grandfather at an Anzac parade ‘thinning to nothing in the wind / like a lie when the truth is out’. Such effects can sometimes seem calculated (there’s an occasional note of rhetoric in Oxley’s speech). Nevertheless, this is writing possessed of enviable vigour, sensitivity and intelligence.

The poetry of Alicia Sometimes betrays an interest in basic questions concerning who we are and where we come from. A lover of astronomy, Sometimes has produced likeable poems that exhibit youthful wonder at the origins of the universe: ‘there was Lego,’ she writes, ‘Lego for life.’ One poem goes so far as to incorporate drawings illustrating evolutionary progress. The following lines accompany a naïve sketch of a flower in bloom: ‘The Sun / liked to wake up /seeds. Dirt was happy.’ Facts are important to Sometimes: ‘an ostrich’s eye is bigger than its brain’; ‘half of our speaking time is made up of pauses.’ But she is still troubled by the failure of language to capture ‘actual’ experience. The poem ‘the word sex’, for example, attempts to simulate intercourse, only to conclude that ‘[t]his thing we call word is not enough’. Among the remainder of Kissing the Curve (Five Islands Press, $9.95pb, 32pp) are poems about Bob Dylan, a Christmas in Melton (‘The summer is too Ken Done’) and the discomfiture of a footballer who unwittingly showed his penis during a game. While the last of these seems in poor taste, Sometimes provides plenty to smile at elsewhere.

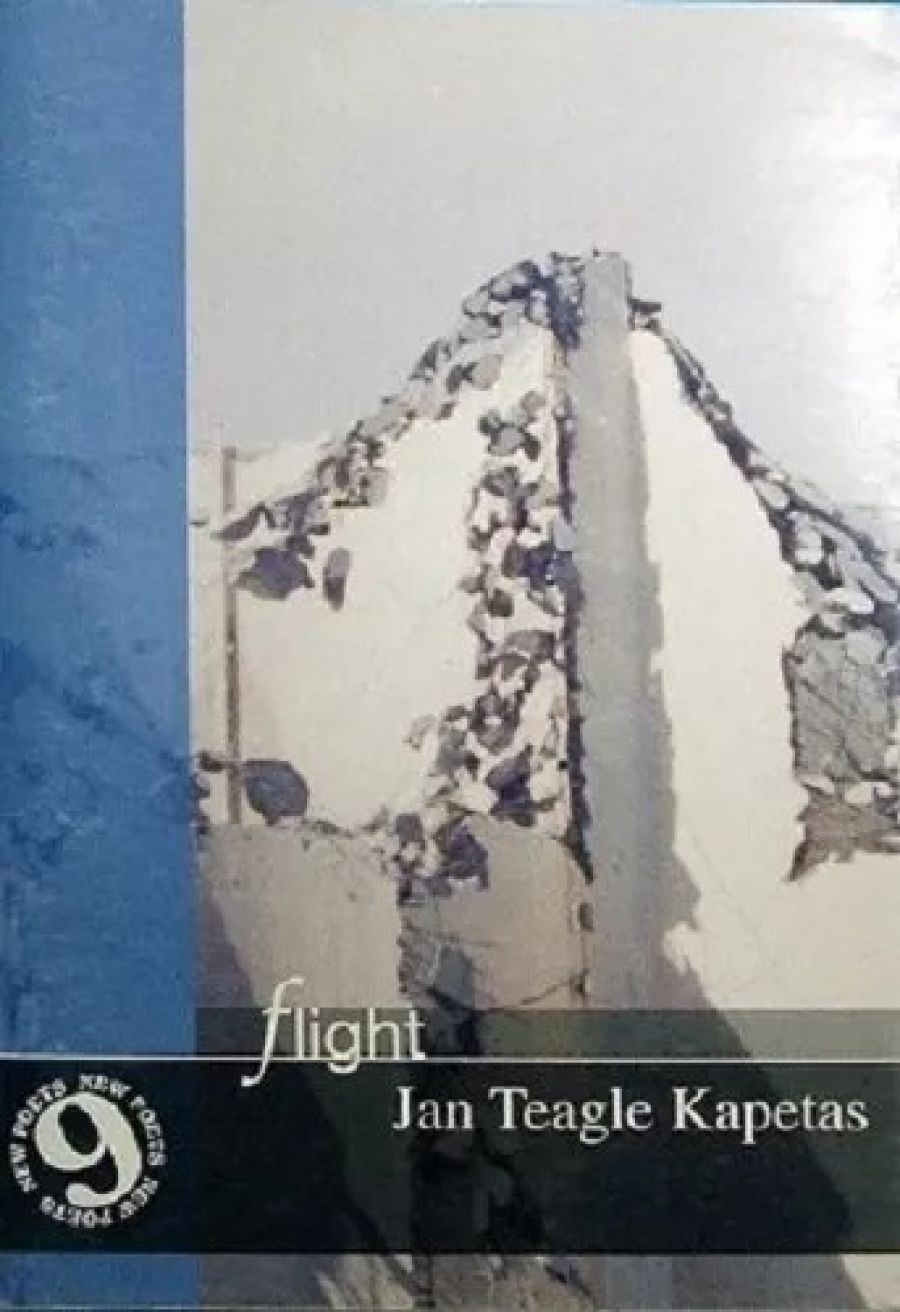

Jan Teagle Kapetas’s poems have an altogether graver aspect. Compassionate and mournful, Kapetas attends to some of the problems facing indigenous people (notably prison suicide and community violence), as well as to the plight of asylum seekers, the events of September 11, and her personal griefs. In the title poem, she describes a mother’s sorrow at the death of her son, killed falling from a tree: ‘Already, this is a memory she cannot compress: / […] It has fallen / like a small egg from the nest of her / expectations, light yet fragile, sure / in its break with time.’ Elsewhere in Flight (Five Islands Press, $9.95pb, 32pp), Kapetas tells of finding her daughter ‘wild’ like ‘an animal’, a stillborn child ‘on the floor, between [her] knees’. These accounts, disturbing and powerful as they are, cannot fail to move the reader. However, one has the feeling that Kapetas might rely too heavily on such material; there are times when a poem can appear to be in the shadow of the thing it describes. So it is heartening to come upon ‘T’ai Song’, which closes the book: ‘I transform your shadow, /draw in the darkness / of your eyes / our infinite outlines of love, / and insist on knowing / no sadness.’

Ross Donlon’s Tightrope Horizon (Five Islands Press, $9.95pb, 32pp) is marred by four or five poems that should never have seen the light of day. Donlon has a whimsical streak that manifests itself in some unforgivable adolescent gaucheries: ‘Future Menu’ adopts the language of recorded information systems (‘To Speak to an Astrologer’ ‘Press the Star Key’); in a ‘do it yourself’ poem, we are asked to consider the experience of visiting Uluru – was it ‘boring / stupid / gay’?; while, in ‘Poetryman’, Donlon compares the poet’s abilities to those of Superman (‘Not Man of Steel / but Man of Feel’). These products of the creative writing workshop are regrettable because Donlon, unaided, can write effectively. He is drawn to the freedom of the road, and much of his best poetry comments on the movement of people and objects through time and space: ‘Fathoms of stars sink through the sky’ (‘Serial Romantic’). There are also good poems here about being in love (‘I take up your hair / half autumn leaves half sun’), a father’s protective relationship with his daughters, and a cancer cell that prepares patiently to kill its ‘host’.

Helen Lambert’s Venus Steps Out (Five Islands Press, $9.95pb, 32pp) is strewn with dead people. ‘Honeymoon’, for instance, delineates the bizarre scene of a man ‘found / kneeling / the poached-white / of his neck / licked by the mistress / only minutes before / his legs froze’. In other poems, Lambert remembers her eccentric grandfather and a ‘[w]axy adolescent girl’ called Audrey; she also chronicles the demise of a neighbour who dreams of the Spanish Armada and eats nothing but peppermint biscuits: ‘We watched her body sink in the wrong waters. A smear of pale chocolate bruised her lips.’ In a manner that brings to mind Eliot’s well-known observations of John Webster, Lambert even manages to make the living seem corpse-like, settling repeatedly on the words ‘skin’ and ‘veins’. Inevitably, some of the writing can be difficult to warm to (one poem, in particular, imagining the humiliation of a judge stripped of his gowns, reads a little too spitefully). But there remains much to enjoy in Venus Steps Out. Above all, Lambert has a knack for creating images at once strange and ordinary. Again, from ‘Honeymoon’: ‘The landlady fell to her knees /letting her pearls bounce / absurdly alive / against her crêpe de Chine breasts.’

Of the six poets under review, Tric O’Heare is alone in giving attention to religion. A lapsed Catholic, O’Heare continues to be sustained – in poetry, at least – by the iconography of her inherited faith: a statue of Mary, propped on an oil drum, watches over the bush, where ‘men shoot at her /because she is there’; another poem, about a visit to Melbourne’s Luna Park, alludes knowingly to the ‘wood and nails’ construction of the scenic railway. Yet, behind the references, there is always doubt. As O’Heare explains, reflecting on her grandmother’s piety: ‘I dare, cowed Catholic child, / to wonder at the inefficacy / of a good woman’s prayer.’ Family affairs occupy a large proportion of Tender Hammers (Five Islands Press, $9.95pb, 32pp); O’Heare has a special interest in the relationship between mother and daughter. While the excursive progress of these poems may be admired, it is only when O’Heare abandons the mode that she really comes into her own. In writing about a wounded dog faced with death on a sinking island, O’Heare succeeds in forgetting herself completely. Thoughtful and cute, the poem is one of the most original of the series.

Comments powered by CComment