- Free Article: No

- Custom Article Title: Masterly Tales

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Masterly Tales

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

How does Arnold Zable do it? After two finely wrought, deceptively simple books on Holocaust themes, he has brought out another, linking tales of the Greek island of Ithaca with the stories of his parents, Polish Jews, and their contemporaries who settled in Melbourne just before or just after the Annihilation, as Zable prefers to call the Holocaust.

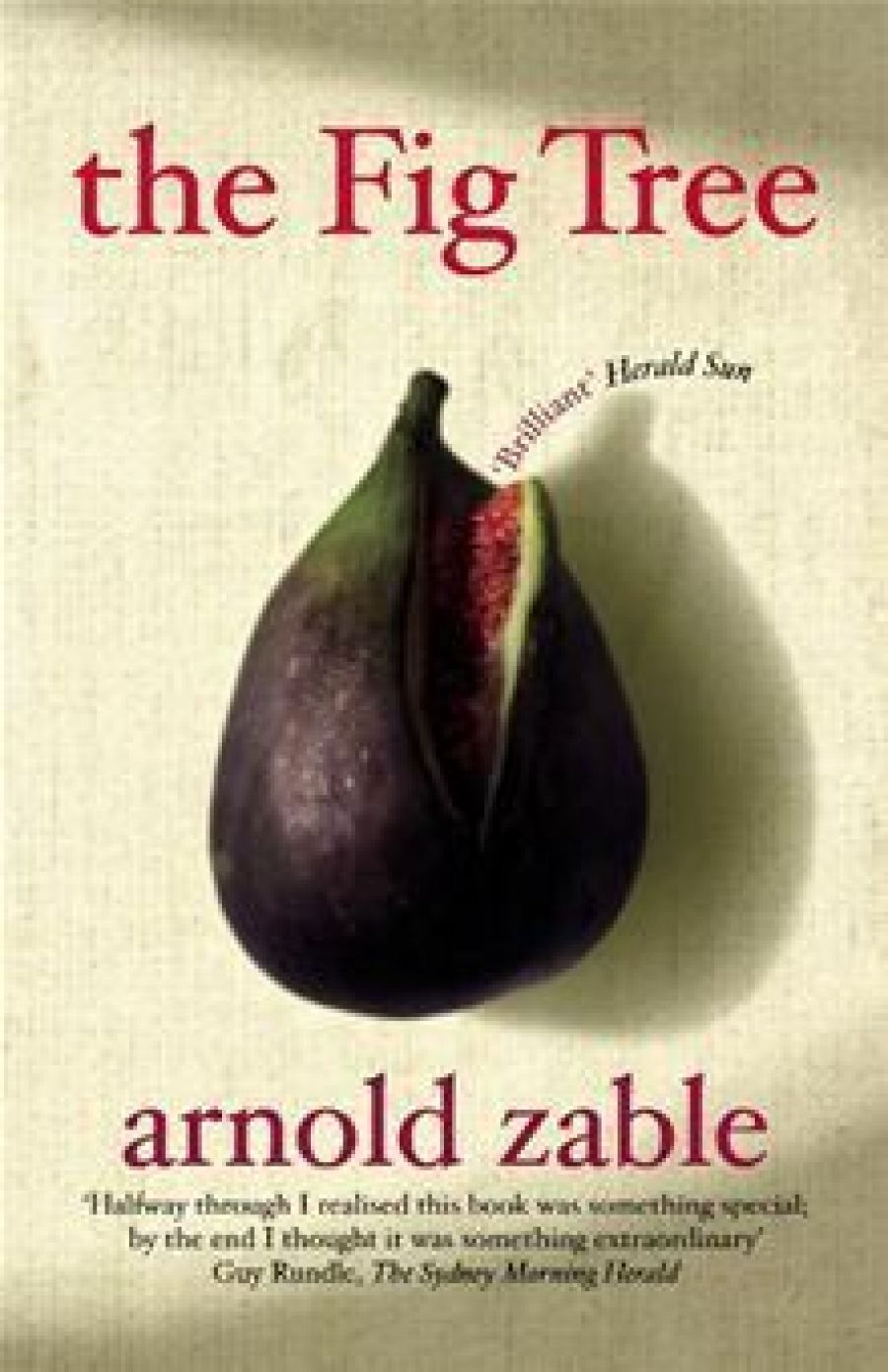

- Book 1 Title: The Fig Tree

- Book 1 Biblio: $27.50 pb, 222 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

It is tempting, and dangerous, for a writer to return perpetually to the obsessions that drive him. The Holocaust and its manifold aftermaths is a literary seam in danger of being mined to exhaustion. But Zable’s heritage, replete with a strong Yiddish-Polish culture, is so rich, his approach so fresh, that his readers will follow him willingly down some well-worn paths.

His prizewinning Jewels and Ashes was a ground-breaking book in Australia, one of the first of what has since become a distinct auto/biographical genre: a second-generation writer returns to the scene of unspeakable crimes to try to understand a fraught and complex legacy, and, in so doing, embarks on a journey into the self.

Café Scheherazade, Zable’s next book, with its central motif of the café where elderly Melbourne Jews meet to schmooze, was an engaging mix of composite characters and harrowing real-life tales that the narrator feels compelled to listen to and record.

And now The Fig Tree, a collection of stories which treads at times on lighter ground, but rarely deviates from the central question: how are we to understand the paradoxes at the heart of the human condition? How do we reconcile cowardice and bravery, evil and good, dark and light? These are the questions we all ask ourselves, even if we never receive lasting or satisfying answers.

Zable is daring in his willingness to examine and re-examine these ancient and much worked-over conundrums. Perhaps his secret is that he is drawn as much to the light as he is to the dark. He compulsively searches for and finds mysterious goodness in the heart of darkness, and he records both with a kind of faux naïveté, a bland simplicity.

It can be a powerfully effective strategy but, in this collection, it took a while to work on me. The first few stories feel a little laboured, and hover on the brink of the obvious. The story of Zable père’s late return to writing poetry before his death reads as if the duty of honouring his father’s memory has put shackles on the son’s prose. In ‘The Record’, I had the feeling that the author’s own hinted-at ambivalent reactions to his mother have been kept at bay, to the story’s detriment. And, while the title story, ‘The Fig Tree’, about the death of his wife’s mother, contains fine passages, it just misses out on its potential for real power. Cliché sneaks in occasionally.

But Zable knows how to build, how to let small ripples widen. As we move on to the evocation of the Greek island earth and air, of its gritty, soil-weathered people, the loosely linked stories begin to reverberate and resound with extra meanings. One story slides effortlessly into another, gives shine and shimmer to the last. And always, light and dark, dark and light.

In ‘Walking Thessaloniki’, he tells us of the town of Thessaloniki, which was wiped clean of its Jews, and of the town of Zakynthos, which saved them all. Zakynthos had a bishop who, when asked to give out the names of the 283 Jews of the town, wrote his own name 283 times. ‘The Ballad of Mauthausen’, another story weaving together Greeks and Jews, past and present, methodically recapitulates brutalities and horrors, but leaves us with a feeling of hope and possibility.

Zable’s approach could easily descend into the inane and sentimental, into a formula that ultimately absolves the reader from drawing the darker and more complicated conclusions. But mostly, like a skilled tightrope walker, he teeters over the abyss and walks into literature. The prose has a lush simplicity that can attain a kind of grandeur. Zable understands and husbands his special gift. ‘To be a writer,’ he says, ‘is, perhaps, to be in a state of childhood; to see, smell, hear, taste and touch things in a state of openness: to be in touch with life itself.’ The theme of childhood innocence is carried, in part, through the presence of his four-year-old son, Alexan-der, a character in his own right, but also a vehicle for that first fresh vision of childhood that Zable seeks. And mostly finds.

There is also a strong sense of place. Zable renders Melbourne’s seaside suburbs and the Greek islands, and their odd parallels, in plain, sinuous prose. He reminds us gently, and without too much overt moralising, of the present-day refugees against whom many people have hardened their hearts.

The book builds into a cunning construction of multiple themes. As we move from the Melbourne stories to the Greek relatives still on Ithaca, and the stories of Greeks and Jews in World War II, and back to the Yiddish theatre and Yiddish writers of pre-war Carlton, Zable is our unobtrusive guide, playing the mere recorder of other people’s stories. But working through each story are interlinking notions of refuge, of the wanderer (Odysseus, an obvious recurring figure), of home, of suffering and renewal.

The master storyteller has done it again.

Comments powered by CComment