- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

When Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude was first published in English, there was an outbreak of what the late Angela Carter called ‘extravagant silliness’. Márquez’s novel was given a rapturous reception that focused on its wondrous exoticism, with scant regard for its grounding in the social and political reality of his native Colombia. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, Carter was prominent amongst English writers who, influenced by South American fiction, began to take an interest in folklore and fairy tales, and to incorporate elements of fantasy into their work. But she recognised that the apparently strange dreams Márquez describes ‘are not holidays from reality but encounters with it.’

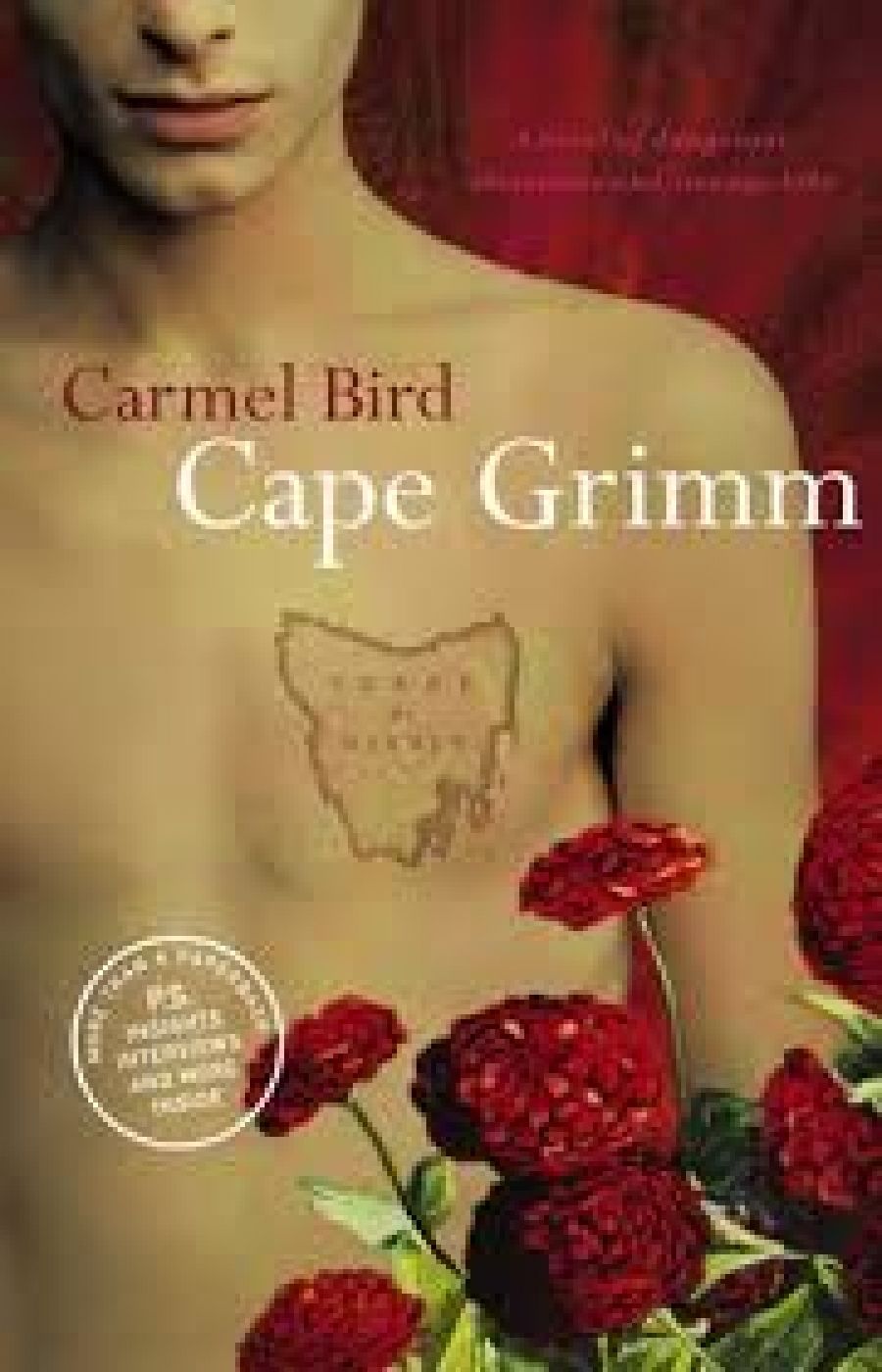

- Book 1 Title: Cape Grimm

- Book 1 Biblio: Flamingo, $29.95 pb, 320 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Cape Grimm, by Carmel Bird, is not an example of the worst-case scenario outlined above. It does, however, sit comfortably within the magic realist tradition. Its narrative explicitly positions itself on the borderline between dream and reality, and there is a conflation of history and fantasy throughout, as suggested by the title, which combines Tasmania’s Cape Grim with the Brothers Grimm. The rollcall of marvels includes ghostly visitations, butterflies writing a name in the sky, and the outrageous coincidence of a shipwrecked woman entering a cave in remote Van Diemen’s Land only to find an exact replica of the couch that furnished her childhood home in South America.

But there is real substance to Cape Grimm. Like Bird’s novel Red Shoes (1998), it focuses on a religious cult. The novel’s central event is the mass murder of a remote Tasmanian community by the cult’s charismatic leader, Caleb Mean. One evening, Caleb leads everyone into the local hall and then sets it alight; the only survivors are Caleb, his lover (Virginia Mean), and their baby daughter. Ten years later, Paul Van Loon, a psychiatrist working in the facility where Caleb is imprisoned, begins writing a personalised account of the tragedy, which forms the bulk of the narrative, interspersed with extracts from Virginia’s journal.

Cape Grimm explores ideas about the powers and responsibilities of the imagination. Culture, it suggests, has the ability to cross boundaries, influencing people’s perceptions in unpredictable ways. Like a fable, the novel also has a cautionary aspect, suggesting that there are dangers in denying the creative impulses of the unconscious. (One of Caleb’s sinister features is that he does not dream.) The tragedy at Skye is ‘a focal point around which the histories […] move and tend’, and Cape Grimm’s web of imagery spins the many hinted connections into something more resonant. The murder is reminiscent of other mass cult killings, such as Jonestown and Heaven’s Gate, but its implications are extended and contextualised by the strange history of the Means and, more broadly, Tasmania’s violent past.

Despite the energy that Bird devotes to establishing these conceits, Cape Grimm never quite gels. To some extent, its weaknesses are personified in its narrator, Paul Van Loon, who lacks all credibility as a psychiatrist. By his own admission, he is a sentimentalist and a former poetaster (not completely reformed: ‘Whose child is this? The sleeping baby girl. We do not know. Who does know? Nobody knows. Nobody knows. Oh woe!’). His account is ‘the poet’s telling of the story’, not the psychiatrist’s, but his insights are alarmingly weak: ‘If there is one thing I have learnt about human beings in my years of study and work in this field, it is that they are devious, and they are incredibly clever.’ (Actually, that’s two things.) Though Van Loon declares his ‘fanciful turn of mind’ from the outset, his willingness to believe in other people’s delusions raises questions about his professional competence. But more importantly, he gives no convincing reason why we should share his beliefs, so Cape Grimm falls into the magic realist trap of working both sides of the street at once: admitting the unsupportable nature of many of its fantasies, but requiring that they be accepted all the same.

Cape Grimm engages with contemporary reality and the implications of the inherited past, and Bird has marshalled an impressive amount of material. There are political overtones, too, with pointed references to children overboard, SIEV-X, and recent controversies about Tasmanian history. But by the end of the novel, its ideas seem diminished rather than supported by the conventional nature of its magic realist elements. It is not just that the government is unlikely to develop a conscience on the strength of three hundred pages of woolly fabulism (they are already accomplished fantasists), but more that the fiction itself might have been better served by being more grounded.

Comments powered by CComment