- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

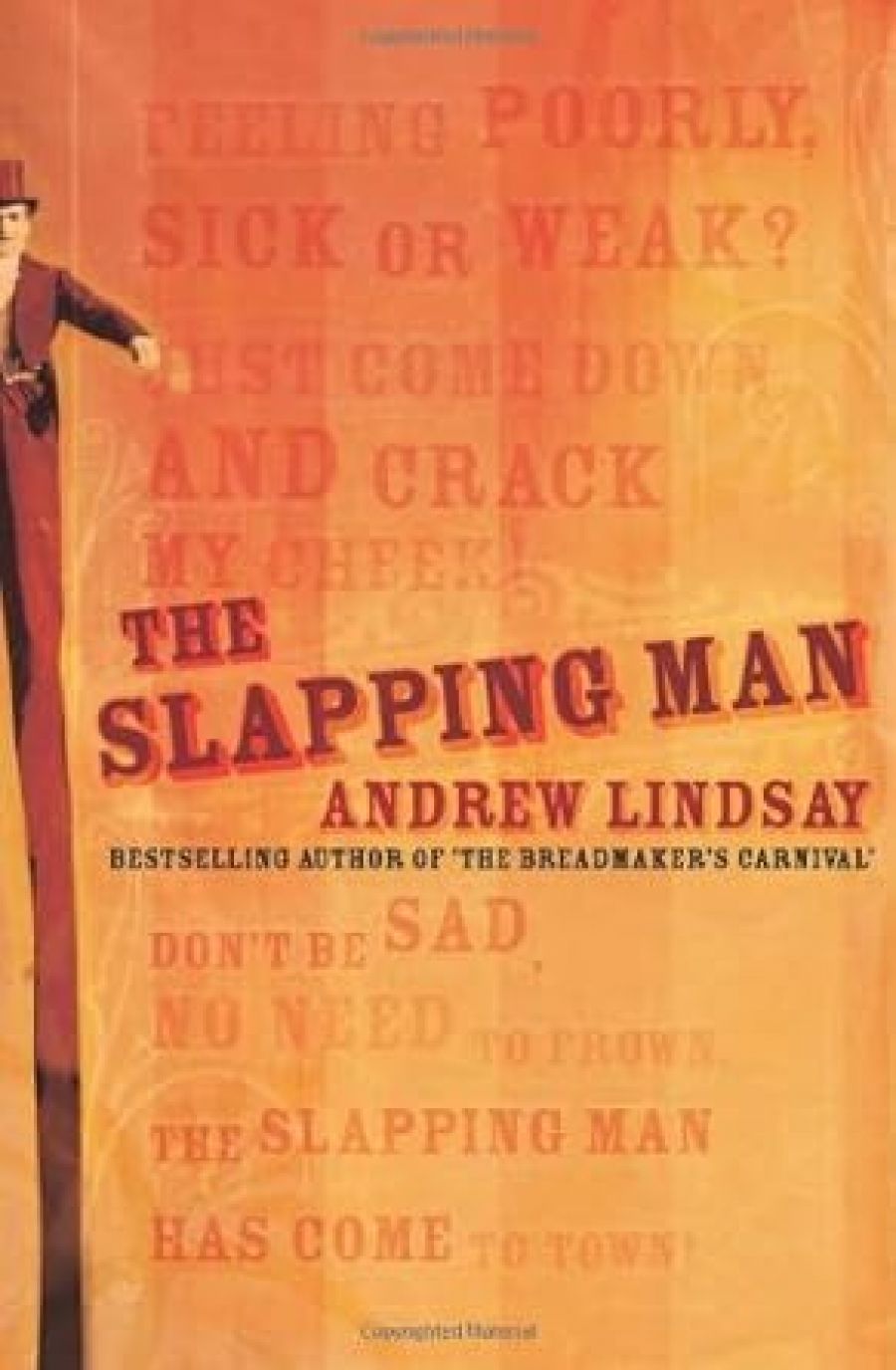

Set in a seaside town whose name changes with the vagaries of its fortunes (Salvation, Ruination, Ridicule), Andrew Lindsay’s Slapping Man is a simpleton called Ernie who discovers a remarkable use for his gargantuan jaw. Determined to transform this facial liability into a money-making asset, he positions himself at the local market next to The Human Pincushion and The Man That Never Laughs and transforms himself into The Slapping Man. As the rhyme on the cover explains, Ernie’s spruiking patter relies on the desire for cathartic violence: ‘Feeling poorly, sick or weak? Just come down and crack my check! Don’t be sad, Don’t need to Frown, The Slapping Man has come to town!’ Owing to the circumstances of his conception and the size of his jaw, Ernie seems to have been destined for a career as a human punching bag, an easy and willing target for malcontents to vent their anger upon. And there are plenty of candidates, considering Salvation’s disaster-riddled history.

- Book 1 Title: The Slapping Man

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $29.95pb, 304pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Ernie’s amazing capacity to withstand pain (potential slappers are advised to wear gloves and to perform various finger exercises so as not to injure themselves) ensures that his popularity reaches hysterical levels. As the frustrated and disillusioned become addicted to this peculiar form of physical therapy, Ernie sees it as a civic obligation to continue proffering his check. With each slap, a sense of well-being envelops the town and, paradoxically, a feeling of peace descends for the first time in its history. However, when a breeding programme is initiated to ensure an offspring with a whopping mandible is available for the next generation of enthusiastic slappers, Ernie realises that being the salvation of Salvation isn’t much fun after all. The mayhem that follows reaches riotous proportions, particularly when Ernie decides to hit back.

Andrew Lindsay was apparently working on The Slapping Man at the same time that his first novel, The Breadmaker’s Carnival, made its tantalising appearance in 1998, and his second book seems to be dipped in the same lurid colours. Once again, Lindsay’s imagination is delightfully subversive. Like its predecessor, The Slapping Man is populated with oddballs and smeared with the juices of birth and death, sex and blood.

However, despite the freak-show elements, Lindsay doesn’t snigger from the sidelines at the physically imperfect and the morally suspect, but maintains an affectionate regard for his parade of grotesques. It’s not their fault that they’re descendants of shipwrecked settlers who crawled on land and committed desperate acts of cannibalism, just as it was perfectly reasonable for the nuns on board to forsake chastity in order to populate the barren land.

Lindsay has worked as a clown. and his theatrical background permeates this novel. Informed by dramatic flair and a fine sense of comic timing, The Slapping Man is as disturbing as it is hilarious. Lindsay’s tableau of human and beastly sacrifice ensures that bright ribbons of sex and violence are threaded throughout the book. Aside from relieving their brutal impulses by killing animals or thwacking The Slapping Man, the citizens also sidle up to the aptly named Virgin Wall to receive gratification from the flesh of Jean Finch. There is no censure or wowser morality about such activities: Lindsay merely describes them with the objectivity of a wildlife documentarian. After all, we are animals, he seems to say, so why bother to deny or sublimate our desires for a spot of sex and bloodletting? As with his first effort, the body’s messy functions and secretions are central to The Slapping Man.

In short episodic chapters, Lindsay and his feckless hero consider how martyrdom and altruism are exploited; how society needs scapegoats to assuage grief, and how the mob mentality focuses its collective antagonism upon a single source of vulnerability. By indulging in self-punishment, Ernie himself seeks atonement for his inaction in standing by while his parents drowned in a fishing accident. In a way, the book is also a tribute to the underdog; Lindsay dedicates it to ‘anyone who ever felt like a slapping man’. After all, instead of cringing about his deformity, Ernie uses it to his advantage. His entrepreneurial spirit enables him to take control of his life and to transform his environment for the better.

The Slapping Man may be the main attraction, but there are many sidekicks and walk-on parts in this garish canvas, and their stories are told in self-contained chapters. There’s Dr Vronsky, the long-suffering counsellor of grief, who has intimate knowledge of the ‘livid entrails’ of the town; John Gobblelard, the lusty publican, who has an inexhaustible appetite for fornication and slaughter; the unfortunate Harness Wilson, so called because his lack of kneecaps means that he has to be wheeled along by his poor daughters; and Jean herself, who has a phobia about kissing after her inamorata drowned and had his lips (among other body parts) nibbled off by sea lice. The dénouement of these intersecting narratives is ingenious, and consolidates Lindsay’s reputation as a consummate storyteller.

A sense of mischief powers the book, and Lindsay’s love of language is evident throughout – in the verbal jocularities of the characters, and also in Salvation’s scurrilous use of nicknames. A dangerous stretch of the coast, for instance, is locally christened ‘The Birth Canal’, and Jean is otherwise known as ‘footie’, because she is passed from hand to hand.

This is magic realism at its best. The Slapping Man is fantastical, bawdy and full of vim. If you like a bit of slap and tickle in your fiction, and aren’t prudish or squeamish, then step right up and marvel at the man with the invincible jaw.

Comments powered by CComment