- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

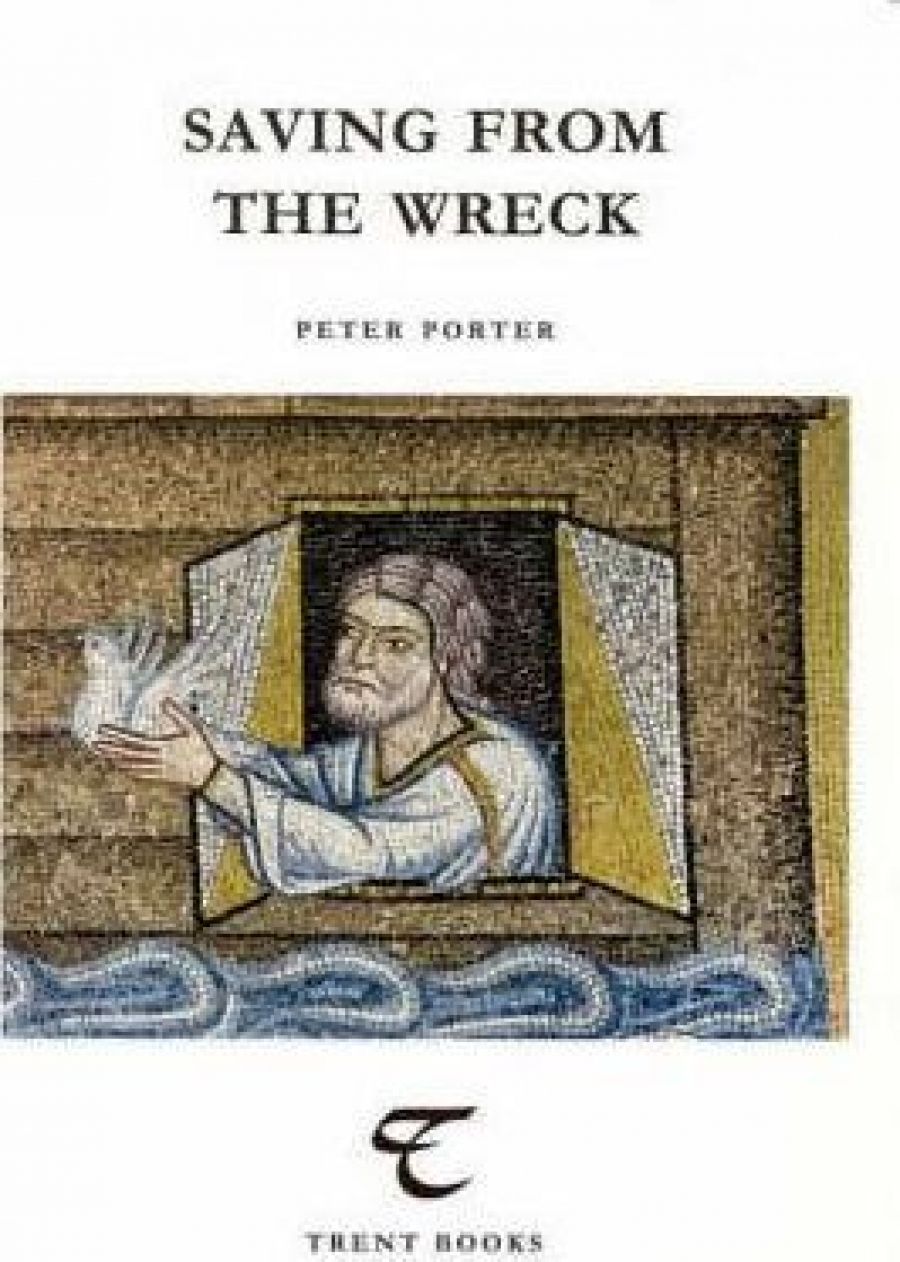

The cover illustration of Peter Porter’s selection of essays shows a mosaic from the Basilica di S. Marco, Venezia, in which Noah leans out from the wall of the Ark and releases the questing dove. The last words of the selection go ...

- Book 1 Title: Saving from the Wreck: Essays on poetry

- Book 1 Biblio: Trent Books, £8.99pb, 216 pp, 9781842330551

But he is always his own man. Here he is on ‘The Shape of Poetry and the Shape of Music’:

The greatest poets have the least need of the arcane: they can make the most shining of structures out of everyday material. What we see is transfigured, but it keeps the lineaments of its ordinariness. Thus the process of inventing a poem and the process of composing music are similarly concerned with thematic transformation. When George Herbert turns cottage brooms and kitchen tables into great religious poetry, he is doing the same thing that Beethoven does with the notes of the common scale … Each true poet has the hard task of quickening the dust of the real, and his only resources are statement, contrast, development and counterpoint – the same as those used by musicians. Prose can afford to argue, to be discursive and compendious. It is like the sounds of Nature: it has not been selected and winnowed for its immaculate shape. Poetry is a selection of words from the whole store available, as music is of natural noises. Thus the two arts are doing the same thing, but they often help each other only as isolated acts of kindness.

Such writing is itself ready ‘to argue, to be discursive and compendious’. To that degree, it falls in with daily social practice: but it always knows where it is going. Porter’s prose imagination, like his poetical imagination, makes provision both for the sweeping view and the telling detail: this is not the first or the last time that he has found George Herbert, whose own habits of mind are in that sense similar, a useful sponsor. And for him, as for Herbert, two elements are constantly important in the process of making: one of these is transformation, and the other is work.

Auden, very unromantically, said that a poem is ‘a verbal contraption’, emphatically a made thing. We call such things ‘works’, and Porter is deeply interested in their own ‘works’, in what makes the wheels go round. He is the least pedantic of critics or of commentators, but he is fascinated by precision and is an adept of the telling detail, whether in poetry or in music: and he wants the words or the notes to earn their passage. But while being an enemy of the gusty, he is as fascinated by processes of transformation as any writer I know. ‘The hard task of quickening the dust of the real’ is a characteristic phrase, capturing as it does both the marvellous and the down-to-earth. In the chapter called ‘A Place Dependent on Ourselves: Poetry and Materialism’, after another salute to Herbert, Porter cites ‘Shakespeare’s famous coups: of Cleopatra at the battle of Actium, “The wind upon her like a cow in June”; of Volumnia reproaching Virgilia in Coriolanus, “All the yarn [Penelope] spun in Ulysses’ absence did but fill Ithaca with moths”; or of Antony, again from Antony and Cleopatra “’Tis the God Hercules whom Antony loved now leaves him.”’ This is Porter country, and it does not stale.

‘Whatever their activity is,’ Canetti wrote, ‘the active think they are better.’ Porter, himself a chasteningly active writer of poetry as of prose, can bring an aquiline eye to writerly activities. ‘Ezra Pound’s injunction to “make it new” would have surprised a Florentine Humanist as much as it would have disgusted him,’ he says; and, in the chapter on translation which lends its title to the book, ‘I think we simply have to admit that much of what passes for translation today is just organised dissemination of misinformation’; and, in ‘The Poet’s Quarrel with Poetry’, ‘A strange paradox is built into much avant-garde poetry, namely that it intends universalism and an uncompromising seriousness while it insists on living in an Arcanum where the ordinary public is treated as a trespasser’. Such thrusts are democratic in spirit, which is not to say that Porter cannot admire the high-wire performers. ‘If Chekhov is a kind of poet, then Wallace Stevens is a cross between Henry James and a serial aphorist,’ he says, in applause; and, ‘In Pope’s poetry, English verse attains for the only time in its history the mellifluousness which Italian poetry enjoys nearly always’.

That ‘Poetry we make from our inadequacy – inadequacy not just of our own minds but of the place we live in, the language we have developed and the moral truthfulness we espouse’ has always been Porter’s own affair, and his tenacity in pursuing it is for me at least as moving as it is admirable. Regarding the activity in others, as sometimes in himself, he keeps as clear-eyed about it as possible. Thus, in ‘Rhyme and Reason’, ‘Satire, however, I hold to be only another version of pastoral, a way poets have of managing to relish what they dislike. They have cause to bless their enemies for existing.’ And thus, in ‘The Couplet’s Last Stand’ (which is on George Crabbe), ‘For a poet his hope and his benison will usually be his energy. What he has to say is often possessed by gloom, but he becomes of the party of hope if he pronounces it with energy and art. How he does so is a great and unexplained mystery.’ This last saying might be an epigraph over the whole of Porter’s work.

Nicolas Bentley said of Henry Campbell-Bannerman: ‘He is remembered chiefly as the man about whom all is forgotten.’ And there we all are, or will be, which is the sort of situation on which Porter thrives, in the sense that even his heroic figures, bringing off triumphs of sight or sound, are unremittingly in touch with mortality. In ‘Rochester: The Professional Amateur’, he says:

His poetry offers one of the best opportunities known to me to study the chronic ambivalence of seriousness in a creative imagination. People being so little capable of reform, the satirist’s railing must defend itself against the charge of self-indulgence. It often does this by going too far. Rochester will almost redeem mankind by making it heroically preposterous. But then his realism intervenes. His poetry, whether in the social form of the couplet, or in lyrics, strives towards a formal satisfaction which its author’s restless imagination will not permit to prevail. His finest works snatch defeat from the jaws of victory, and do it in the name of truth.

A passage like this bears the marks of completely original attention to Rochester while shedding light on its author’s own practice and policies. For Porter is almost always concerned with the cross-hatching which defines the human as we have it, with Pope’s ‘being darkly wise, and rudely great’. He says at one point: ‘while I relish Tennyson’s prelapsarian lyricism, I feel in Browning the wind of that other planet, the Twentieth Century.’ Prelapsarian he certainly is not: but he stands before us like an experienced Adam, to say that half an apple is better than none at all.

Comments powered by CComment