- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Custom Article Title: The importance of reverie

- Review Article: No

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The traits women are encouraged to develop nowadays, such as outwardness, attitude, assertiveness, and professionalism, did not characterise Grace Cossington Smith (1892–1984). Family snapshots showed the young woman with tousled hair, guileless face, and buck-toothed smile: a neat-figured, long-skirted Edwardian tomboy after the style of Australian heroines in novels by Ethel Turner and Mary Grant Bruce. The older woman in family photographs still had the tomboy grin; conversely, when she showed a public face, the mouth was closed and the eyes steady behind glasses.

Cossington Smith was reasonably well known in her modernist youth, less so in later years, until, in 1973, Daniel Thomas organised a retrospective at the Art Gallery of New South Wales that launched her as probably the major artist of her generation. For Thomas, the key to her art was colour and spirituality: ‘all her paintings are devotional’. In particular, he thought that the interiors of ‘Cossington’, the well-loved family home, in a series of late works vibrant with light and memory, were the artist’s reflections on the human values of ‘security, serenity and stability … precarious and hard-won’. The late, great interiors also dominate this second, splendid retrospective, organised by Deborah Hart of the National Gallery of Australia, and now showing at the Art Gallery of South Australia. The selection and display of works suggests to me that the tug of inner and outer worlds, of exploration and revelation, informed Cossington Smith’s art from first to last. One creative source was within home and family, the artist’s suburb of Turramurra (adjacent to the bushland of Kuringai Chase, on the north shore of Sydney) and a small coterie of friends. The other was the contemporary Western world as it affected Sydney in both world wars: industrial disputes, crowds filling the man-made canyons of city streets, and the spanning of Sydney Harbour by an iron bridge, the bold arch of which gave form to what, before, had been mere empty space. Cossington Smith was unusual among Australian modernists of her generation in visualising the emotions shared by people within a group. As well as picturing race-going crowds, strikes, commuters at peak hour, marching troops, she took her sketchbook into churches and theatres to describe the sharing of religious ritual and performances of music and ballet.

A ceremonial preparation and ritual bridged Grace’s inner and outer worlds. Jean Appleton, who used to accompany Cossington Smith on painting expeditions, described her equipped with ‘a huge black brolly, painting materials, stool, packed lunch … plus a home-made padded box to insulate her feet from the insects and elements’. More significantly, Cossington Smith had a bridge to painting in the practice of drawing. The works in this retrospective are displayed with some drawings, plus a digital slideshow of other relevant sketches. Drawing was not a mere rehearsal of painting: a typical drawing by Cossington Smith was a diagram or plan. Its form was almost the negative to painting in that the drawn outlines would be replaced in the oil painting by implied edges and the drawing’s blank spaces would be built with substantial bricks of colour.

The selection from early, middle, and late phases of the artist’s work conveys the idea that the preparation for the final phase was not simply the vitalist 1920s and 1930s paintings that show life in action: a road or a ship swelling upward or plummeting, waves advancing, plants growing, crowds rushing, the Harbour Bridge soaring into the sky. Those paintings were exploratory, many of them searching the styles and motifs of inspirational masters (Christopher Nevinson, Paul Nash, Roland Wakelin, Paul Cézanne, Wassily Kandinsky, Vincent van Gogh) as a provisional way of scrutinising the subject in life. Their imaginative trajectory is outward to the stylistic exemplars, to modern theories of art and religion, and to life seen through special lenses. Revelation was built into the form according to how Cossington Smith achieved command over her chosen sources.

This exhibition points to the significance of hesitation for the mature work. In some nondescript, mid-career works, Cossington Smith seems poised for revelation, looking to her subject and working very plainly without the guide of a masterly style. I take it that Hart, by including so many of the muted paintings, is suggesting that the essential preparation for the late interiors in yellow was the quiet representation of brown, untidy bush, of blond fields hemmed in a stop-and-go fashion with fences and electricity poles, and flower paintings with dull, autumnal colours and indeterminate structure. Among the handful of memorable paintings in the group are a couple in tones of bronze and olive, mere formless samples of the bush, in which the subject appears to be the threshold in time between a summer’s day and night. The atmosphere is blurring to dusk, the leaves of the trees (evidently still warm from the sun) are relaxed in form, and oily and semi-transparent in texture. In the late 1930s Cossington Smith painted Bonfire in the bush. Night prevails except where a plume of flame and smoke lights some figures gazing into the fire and shows a path leading through the dark from us to them. Patrick White (who once owned the work) wrote ambiguously, ‘this glowing icon is important because it conveys a communion between the Edwardian ascendancy and the original Australia’. Treania Smith (of Macquarie Galleries) noted Cossington Smith’s ‘great concentration’ during the mid-career painting excursions. Her manner of brushing, from one corner of the canvas steadily across the whole work, suggests that she worked from a mental template of the composition, colour and emotion: the preparatory bridge evidently served even those works, the closest she ever came to direct, spontaneous painting. Unlike the sharing of emotions between people in a group, the ‘communion’ involved in landscape painting depended on the artist waiting for a subject to come forward. As Hart observes, many of these paintings ‘work gradually’.

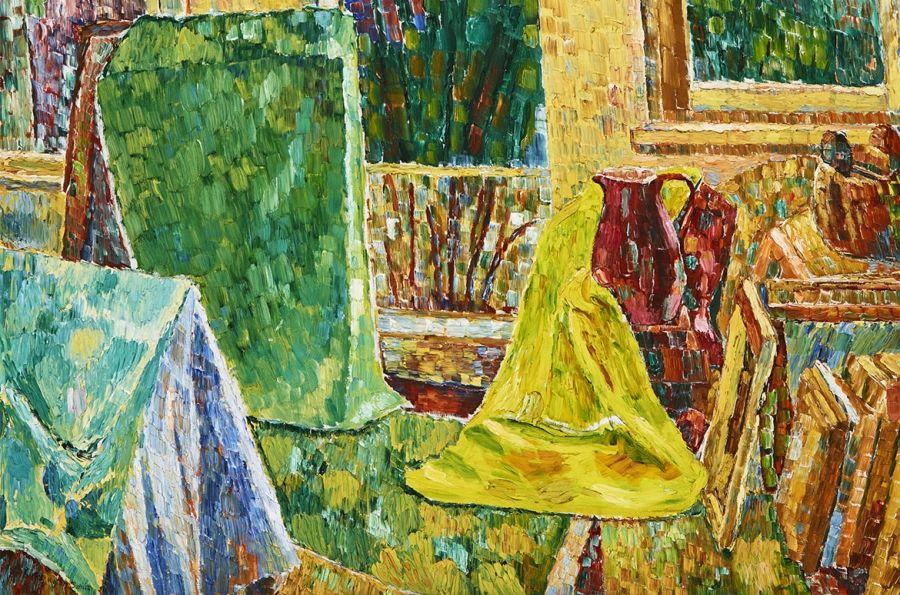

Cossington Smith has attracted some notable writers: Drusilla Modjeska in Stravinsky’s Lunch (1999), Bruce James in Grace Cossington Smith (1990), Thomas first of all, and now Hart. All have noted the importance to Cossington Smith of reverie. James observed that she ‘meditated’ on a motif for long periods, ‘with due sensitivity to its elusiveness and inscrutability’. Modjeska imagined her occupying a ‘transitional’ or ‘sheltered’ space: ‘The Buddhists talk of “bare attention” as the capacity to be at ease with oneself, to … attend to the world simply as it is.’ Thomas found her paintings devotional. Hart saw that the effect could be gradual. It seems that for Cossington Smith the scope for personal ease shrank over time whereas her spiritual scope expanded. She stopped communing with the quiet bush: ‘by slow degrees I gave that up … I began to feel not so secure somehow.’ Eventually, even the garden of ‘Cossington’, her home, was to loom outside and at several removes from the centre of her attention. The last great paintings are of rooms with doors opening over a deep threshold onto a verandah beyond which the garden glows. She painted rooms in which she had lived and slept since her youth, opening drawers and closet doors to show what is stored within. Merely by changing the angle of a door or mirror, or by opening a drawer she was able to redefine the plastic space in which she moved and had her being. The final paintings in the exhibition are of life’s familiar vessels: jugs and jars brimmed with light.

Writers and viewers agree about the art of Grace Cossington Smith. From within her home environment, she addressed large issues. There are paintings in this exhibition that deal with the politics and dangers of war, the psychology of crowds, the powerful effect of technology on the natural world, the rising crescendo of music and the exhalation of the spirit. She realised those themes with the confidence of an Edwardian woman looking outward from her home position rather than from a professional position in the art community. However, the peak of her art was within her home and the memories it held.

Catalogue:

Deborah Hart (ed.)

Grace Cossington Smith

NGA, $89 hb, 187 pp, 0 642 54114 0

$59.95 pb, 0 642 54203 1

Exhibition:

Grace Cossington Smith

Art Gallery of South Australia

Closes 9 October 2005

Comments powered by CComment