- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Literary Studies

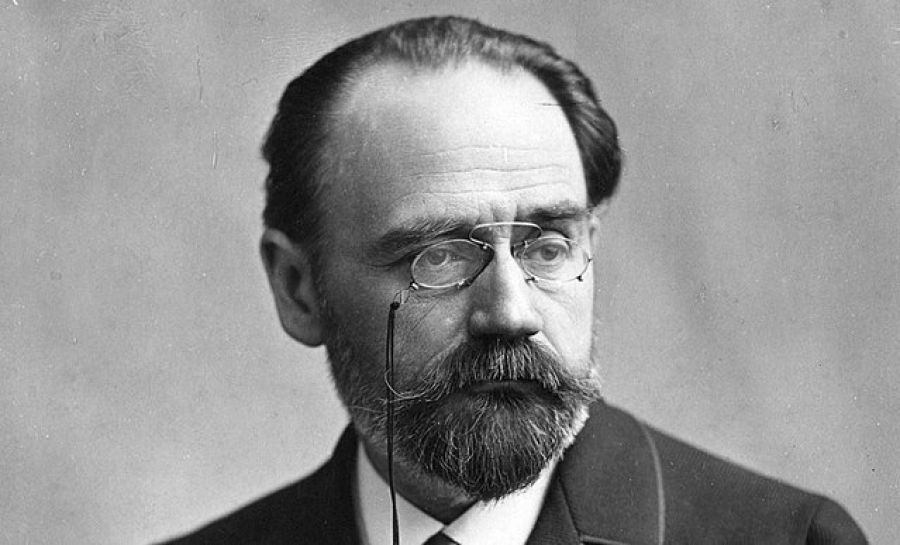

- Custom Article Title: Émile Zola

- Review Article: No

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Unlike Flaubert, the ‘hermit of Croisset’, who turned away from his age in an attitude of ironic detachment, Émile Zola (1840–1902) embraced his century in a way no French writer had done since Balzac. Zola’s ambition was to emulate Balzac by writing a comprehensive history of contemporary society. Through the fortunes of his Rougon-Macquart family, he examined methodically the social, sexual, and moral landscape of the late nineteenth century along with its political, financial, and artistic contexts. Zola is the quintessential novelist of modernity, understood in terms of an overwhelming sense of tumultuous change.

Zola’s epic type of realism is reflected not only in the vast sweep of his work, but also in its variety and complexity. In addition to his thirty-one novels, he wrote five collections of short stories, a large body of art, drama and literary criticism, several plays and libretti, and numerous articles on political and social issues published in the French press at various stages of his career as a journalist. He was actively engaged in his age. He was a major critic of literature and painting, and a significant political commentator long before the Dreyfus Affair. His main achievement, however, was his twenty-volume novel cycle, Les Rougon-Macquart, which was to rival Balzac’s Comédie humaine. In eight months, during 1868 and 1869, Zola outlined the twenty novels he intended to write on the theme of heredity: a family, the Rougon-Macquarts, tainted with alcoholism and mental instability, were to intermarry, to proliferate and to pass on their inherited weaknesses to subsequent generations. Their fortunes would be followed over several decades. Zola began work on the series in 1870 and devoted himself to it for the next quarter of a century.

The family is descended from the three children, only one legitimate, of an insane woman, Tante Dide, who dies in a lunatic asylum in the last volume of the series, Le Docteur Pascal (Doctor Pascal, 1893). Dide has two partners, and produces three main branches of the family, who spread through all levels of society. The Rougons, the first (legitimate) branch, prospers, their members rising to occupy commanding positions in the worlds of government and finance. Son Excellence Eugène Rougon (His Excellency Eugène Rougon, 1876) describes the corrupt political system of Napoleon III, and two novels linked by the same protagonist, Saccard, La Curée (The Kill, 1872) and L’Argent (Money, 1891), evoke the world of business and the feverish contemporary speculation in real estate and stocks. The second branch of the family is the Mourets, some of whom are successful bourgeois adventurers. Octave Mouret, a young bourgeois on the make, is an ambitious philanderer in Pot-Bouille (Pot Luck, 1882), a savagely comic picture of the hypocrisies and adulteries behind the façade of a new bourgeois apartment building. In Au Bonheur des Dames (The Ladies’ Paradise, 1883), the virtual sequel to Pot-Bouille, he is shown making his fortune from women, as he creates the first great Parisian department store. The Macquarts are the working-class members of the family. Members of this branch figure prominently in all of Zola’s most powerful novels: Le Ventre de Paris (The Belly of Paris, 1873), which uses the central food markets, Les Halles, as a gigantic figuration of the greed of the petty bourgeoisie; L’Assommoir (1877), a powerful depiction of the lives of the working class in the slums of Paris; Nana (1880), the novel of a celebrated courtesan of working-class origins whose powerful sexuality spreads destruction through the imperial court; Germinal (1885), perhaps Zola’s most famous novel, presenting life in a coal-mining region of northern France; L’Oeuvre (The Masterpiece, 1886), the story of a half-mad painter of genius, set in the world of art and artists, and including a number of prominent literary and artistic figures of the period; La Terre (Earth, 1887), in which Zola brings an epic dimension to his depiction of peasant life; La Bête humaine (The Beast in Man, 1890), which opposes the technical progress represented by the railways to the homicidal mania of an engine-driver, Jacques Lantier; and La Débâcle (1892), with its grim account of the military defeat of France in the 1870 war with Prussia, which brought about the collapse of the Second Empire and the Paris Commune of 1871.

Auerbach concludes his comments on two passages from Germinal with these remarks:

Zola knows how these people thought and talked. He also knows every detail of the technical side of mining; he knows the psychology of the various classes of workers and of the administration, the functioning of the central management, the competition between the capitalist groups, the cooperation of the interests of capital with the government, the army. But he did not confine himself to writing novels about industrial workers. His purpose was to comprise – as Balzac had done, but much more methodically and painstakingly – the whole life of the period (the Second Empire): the people of Paris, the rural population, the theatre, the department stores, the stock exchange, and very much more besides. He made himself an expert in all fields; everywhere he penetrated into social structure and technology. An unimaginable amount of intelligence and labour went into the Rougon-Macquart.

As a writer, Zola was, in many respects, a typical product of his times. This is most evident in his enthusiasm for science and his acceptance of scientific determinism, which was the prevailing philosophy of the latter part of the nineteenth century. Converted from a youthful romantic idealism to realism in art and literature, Zola began promoting a scientific view of literature inspired by the aims and methods of experimental medicine. He called this new form of realism ‘naturalism’. His fourth novel, Thérèse Raquin (1867), a compelling tale of adultery and murder, applied these ideas and attracted much critical attention. The subtitle of the Rougon-Macquart cycle, ‘A Natural and Social History of a Family under the Second Empire’, suggests Zola’s two interconnected aims: to use fiction to demonstrate a number of ‘scientific’ notions about the ways in which human behaviour is determined by heredity and environment; and to use the symbolic possibilities of a family whose heredity is tainted to represent a diseased society – the immoral and corrupt, yet dynamic and vital, France of the Second Empire (1852–70). Zola set out, in the Rougon-Macquart cycle, to tear the mask from the Second Empire, and to expose the frantic pursuit of appetites of every kind that it unleashed. He was influenced by Balzac; by the views on heredity and environment of the positivist philosopher and cultural historian Hippolyte Taine, whose proclamation that ‘virtue and vice are products like vitriol and sugar’ he adopted as the epigraph of Thérèse Raquin; by Prosper Lucas, a largely forgotten nineteenth-century scientist, author of a treatise on natural heredity; and by the Darwinian view of man as essentially an animal (a complete translation of Darwin’s The Origin of Species, first published in 1859, had appeared in French in 1865). Zola himself claimed to have based his method largely on the physiologist Claude Bernard’s Introduction à l’étude de la medicine expérimentale (Introduction to the Study of Experimental Medicine), which he had read soon after its appearance in 1865. The ‘truth’ for which Zola aimed could only be attained, he argued, through meticulous documentation and research; the work of the novelist represented a form of practical sociology, complementing the work of the scientist, whose hope was to change the world not by judging it but by understanding it. When the laws determining the material conditions of human life were understood, man would have only to act on this understanding to improve society. Zola, in other words, was an early advocate of ‘social engineering’. Much of his thinking, especially in his later work, is stamped with the progressive values of the Enlightenment.

Zola was most truly a ‘naturalist’ (in the sense of being a writer who based his fiction on scientific theory, and in particular on methods developed by the natural sciences) in the early novels Thérèse Raquin and Madeleine Férat (1868). In his uncompromising preface to the second edition of Thérèse Raquin, he defended the ‘scientific’ purpose of the book: namely, a physiological rather than psychological analysis of the ‘love’ that brings two people of differing ‘temperaments’ together, and an attempt to present as an entirely physical, ‘natural’ process, the ‘remorse’ that follows their murder of an inconvenient husband. Theory and practice had diverged considerably by the time, over a decade later, he wrote his polemical essay ‘Le Roman expérimental’ (‘The Experimental Novel’, 1880). But in any case, Zola’s naturalism was not as naïve and uncritical as is sometimes assumed. His formulation of the naturalist aesthetic, while it advocates a respect for truth that makes no concessions to self-indulgence, shows his clear awareness that ‘observation’ is not an unproblematic process. He recognises the importance of the observer in the act of observation, and this recognition is repeated in his celebrated formula, used in ‘The Experimental Novel’, in which he describes the work of art as ‘a corner of nature seen through a temperament’. He fully acknowledges the importance, indeed the artistic necessity, of the selecting, structuring role of the individual artist and of the aesthetic he adopts. It is thus not surprising to find him, in a series of newspaper articles in 1866, leaping to the defence of Manet and the Impressionists – defending Manet as an artist with the courage to express his own temperament in defiance of current conventions. Zola’s brilliant critical ‘campaign’ made Manet famous. Not only did he understand what modern painters such as Manet were doing, but he was able to articulate it before they could.

Zola’s representation of society is informed by a vast amount of dedicated first-hand observation, note-taking and research – in Les Halles, the Paris slums, the department stores, the theatre, the coal fields, the railways, the French countryside. Zola took his notebook down a mine to write Germinal; he travelled in a locomotive and studied the railway system and timetables to write The Beast in Man. He combines the vision of a painter with the approach of a sociologist and reporter in his observation of the modes of existence, the patterns, practices and distinctive languages that characterise particular communities and milieux. The texture of his novels is infused with an intense concern with concrete detail; and the detailed preparatory notes he assembled for each novel represent a remarkable stock of documentary information about French society in the 1870s and 1880s.

Zola is above all, however, a narrative artist. His fiction acquires its power not so much from its ethnographic richness as from its imaginative qualities. His novels are built in massively constructed blocks, huge chapters cemented together by recurring leitmotifs and a consummate gift for storytelling. In his narrative practice, he combines brilliantly the particular and the general, the individual and the mass, the everyday and the strange. His various narrative worlds, with their specific atmospheres, are always presented through the eyes of individuals, and are never separate from human experience.

The interaction between people and their environment is evoked in Zola’s famous physical descriptions, which form such a prominent aspect of his novels. These descriptions are not, however, mechanical products of his aesthetic credo, objective ‘copies’ of the real; rather, they express the very meaning, and ideological tendencies, of his narratives. Consider, for example, the lengthy descriptions of the luxurious physical décor of bourgeois existence in The Kill. The main syntactic characteristic of these descriptive passages is the eclipse of human subjects by abstract nouns and things, suggesting the absence of any controlling human agency, and expressing a vision of a society that, organised under the aegis of the commodity, turns people into objects. Similarly, the descriptions of the sales in The Ladies’ Paradise, with their cascading images and rising pitch, suggest loss of control, the female shoppers’ quasi-sexual abandonment to consumer dreams, at the same time mirroring the perpetual expansion that defines the economic principles of capitalism. Description of the physical realities of workers’ lives reinforces the radicalism of novels such as L’Assommoir and Germinal by pointing insistently to conditions of labour that are monstrously unjust.

Zola’s descriptive style reveals a genius for dramatic pictorial representation. Did anyone before him see a tenement house as he did in the second chapter of L’Assommoir? Descriptions become highly metaphorical; the observed reality of the world is the foundation for a poetic vision. The originality of Zola’s fiction lies in its movement, colour and intensity; and especially in its remarkable symbolising effects. Emblematic features of contemporary life – the market, the machine, the tenement building, the laundry, the mine, the apartment house, the department store, the stock exchange, the theatre, the city itself – are used as giant symbols of the society of his day. Zola sees allegories of contemporary life everywhere. In The Kill, the new city under construction at the hands of Haussmann’s workmen becomes a vast symbol of the corruption, as well as the dynamism, of Second Empire society. Zola’s fictional naturalism becomes a kind of surnaturalism, as he infuses the material world with anthropomorphic life, magnifying reality and giving it a hyperbolic, hallucinatory quality. The play of imagery and metaphor often assumes phantasmagoric dimensions. We think, for example, of Saccard in The Kill, swimming in a sea of gold coins – an image that aptly evokes his growing mastery as a speculator; or the fantastic visions of food in The Belly of Paris; the still in L’Assommoir, oozing with poisonous alcohol like some malevolent beast, and Goujet’s forge, where machines become giants and the noise of the overhead connecting belts becomes the flight of night birds; Nana’s mansion, like a vast vagina, swallowing up men and their fortunes; the dream-like proliferation of clothes and lingerie in The Ladies’ Paradise; the devouring pithead in Germinal, lit by strange fires, rising spectrally out of the darkness.

Realist representation is imbued with mythic resonance. The Belly of Paris is simultaneously a description of Les Halles and the story of the eternal struggle between the Fat and the Thin. Germinal offers perhaps the most obvious examples of the fusion of reality and myth: the pithead, Le Voreux, is a modern figuration of the Minotaur, and is constantly compared to a monstrous beast which breathes, devours, digests and regurgitates. Reality is transfigured into a theatre of archetypal forces. Zola’s fascination with these forces, and their central role in his creative project, are reflected in his repeated use of the word ‘poem’ in the preparatory sketches for his novels: Nana will be a ‘poem of male desire’; The Ladies’ Paradise will be a ‘poem of modern activity’.

Zola’s use of myth is inseparable from his vision of history, and is essentially Darwinian. His conception of society is shaped by a biological model informed by a constant struggle between the life instinct and the death instinct, the forces of creation and destruction. His social vision reflects an ambivalence characteristic of modernity itself – a pessimistic attitude towards the present, but optimism about the future. Progress, for Zola, cannot be imagined without a form of barely contained primitive regression, as witnessed by Jacques Lantier’s feelings of both veneration and destructive hatred towards his locomotive in The Beast in Man. Despite his faith in science, Zola’s vision is strongly marked by the anxiety that accompanied industrialisation and modernity. Scientific and technological progress brings alienation as well as liberation, and modern man feels trapped by forces he has created but cannot fully control. The demons of modernity are figured in images of destruction and catastrophe: the sinister still in L’Assommoir, the labyrinthine Le Voreux in Germinal, the suicidal and ultimately destructive locomotive in The Beast in Man, the city in flames in La Débâcle. Zola’s naturalist world is an entropic world, in which nature inevitably reverts to a state of chaos, despite all human effort to create order and to dominate its course. But there is also emphasis on regeneration, on collapse being part of a larger cycle of integration and disintegration. Zola’s work always turns towards hope, as the very title of Germinal implies.

It is the mythopoeic quality of Zola’s work that makes him one of the great figures of the French novel. Heredity serves as a structuring device, analogous to Balzac’s use of recurring characters; and it has great dramatic force, allowing Zola to give a mythical dimension to his representation of the human condition. For Balzac, money and ambition were the mainsprings of human conduct; for Zola, human conduct was determined by heredity and environment, and they pursue his characters as relentlessly as the forces of fate in an ancient tragedy. As well as looking back to Balzac, Zola points forward to Proust – in the huge sweep of society he presents, in his treatment of political and sexual themes, in his close attention to the particular idiom of individuals or groups, even in his representation (as in The Kill and Nana) of transvestism and homosexuality; but especially in his intense awareness of the disruptive effect of sex in breaking up formerly solid class barriers.

In 1876 Zola published in serial form his first working-class novel, L’Assommoir, which focuses on the life and death of a Parisian washerwoman, Gervaise Macquart. The following year, when the novel appeared in book form, he added a preface in response to the storm of controversy the novel had provoked. He characterised L’Assommoir as ‘a work of truth, the first novel about the common people which does not tell lies but has the authentic smell of the people’. Of course, peasants and workers had figured in French fiction since the eighteenth century. The urban poor had been the subject of Eugène Sue’s Les Mystères de Paris (The Mysteries of Paris, 1842–43) and Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables (1862), and in 1864 Edmond and Jules de Goncourt had published Germinie Lacerteux, a proto- naturalistic novel about a maidservant. But the violently hostile reactions to L’Assommoir of Zola’s bourgeois readers (who noisily accused him of pornography), together with the novel’s immense success (there were ninety-one editions in the five years following its publication), indicated that something significantly new had happened to the French novel.

The novel was essentially a bourgeois genre, having developed in tandem with the bourgeoisie’s political and material rise. It depended on a largely bourgeois readership, and was shaped by a bourgeois ideology of literary propriety. To focus entirely on urban workers was itself new and disturbing. A working-class washerwoman, moreover, becomes, in L’Assommoir, a tragic heroine. If the workers could take over the novel, perhaps they could also take over the government; the trauma of the Commune of 1871, when the people of Paris had repudiated their national government and set up their own government, was still fresh in people’s minds. The workers are intrusively present – they can be ‘smelt’ – in the very language of L’Assommoir. Language itself is – aggressively and provocatively – socialised. One of the most original features of L’Assommoir is Zola’s use of free indirect discourse, by which the workers’ language, the lexicon and syntax of the streets, suffuses not only the novel’s spoken dialogue but also its narrative voice. Zola’s brilliant ability to capture the patterns and rhythms of popular speech, even when writing indirectly, not only reflects his powers of psychological empathy, a capacity for evoking the workers’ own vision of the world, but also has important political implications. It was this bold experiment with style that, according to Zola, explained why his bourgeois readers had been so upset. As he wrote in his preface: ‘They have taken exception to the words. My crime is that I have had the literary curiosity to collect the language of the people and pour it into a carefully wrought mould. The form! The form is the great crime.’ His ‘great crime’ was to have shown that the novel is not an intrinsically bourgeois genre, tied to bourgeois discourse. Who speaks in L’Assommoir? Not the bourgeoisie but, apparently, the workers!

What also greatly disturbed bourgeois critics was Zola’s graphic portrayal – unprecedented in French fiction – of the workers’ physical being, their bodies. Bourgeois thought concealed both the bourgeoisie’s physical nature and the workers’ humanity; and this meant that Zola’s emphasis on the body, by forcing the reader to recognise that the human condition is a universal, had a powerful subversive effect on the ideological justification for the capitalist hierarchy. As Jean Borie has argued, the bourgeoisie devised a complex mental system in which the body and the proletariat were alien and subservient. In the artistic myths communicating that system, the body was either pornographic or subsumed by the soul, while workers, when not invisible, were either vicious drunkards or inspiringly resigned labourers on the way to becoming bourgeois. Zola was doubly obstreperous. He neither ignored the proletariat and the body nor did he present them in suitable guise – and this was a monstrous violation of aesthetic, moral and political principles held by all right-thinking men. Zola showed his readers things they would prefer not to see in a style making it impossible to look the other way. The strident attacks on L’Assommoir for pornography were motivated as much by reactionary fear as by prudishness.

Eight years after L’Assommoir, Zola published Germinal. Through his description of a miners’ strike, he evokes the awakening of the workers’ political consciousness. Para- doxically, it is in his portrayal of the miners’ material and mental condition before their consciousness is aroused by their would-be leader, Étienne Lantier, that Zola is parti- cularly subversive. The miners have a sense of social authority as a force in its own right, inscribed into the natural order of things. Their vision of the world is, in the Marxist sense, alienated. One of the strengths of Germinal is its demonstration of the ways in which bourgeois mystification and working-class alienation complement each other in the reinforcement of the dominant ideology. Like Marx, Zola saw that the true significance of social processes goes on ‘behind the backs’ of individual agents.

In L’Assommoir Zola had used narrative technique, and narrative voice in particular, to make articulate the inarticulate – to make us see and hear the world through the workers’ eyes and voices. In Germinal, he does something similar; but in the later novel he also depicts a moment in history when the workers find a political voice. The theme of the miners’ learning to speak becomes a motif of the novel. Auerbach analyses the evening conversation between Étienne Lantier and the Maheu family in the third chapter of Part Three of Germinal – intended as one example of many such conversations – to show the stirrings of the miners’ consciousness of their situation in response to Étienne’s political eloquence. The narration in the second chapter of Part Four of the visit of the miners’ delegation, led by Maheu, to the mine- manager’s house shows how the miners, though at first intimidated by the imposing surroundings (manifestations of the bourgeois world) and by their unaccustomed role (making demands rather than following orders), begin to speak and slowly gain in confidence as they articulate their grievances. And Maheu, their chosen spokesman, most of all: at first tongue-tied, reproached by the manager Hennebeau for heading a party of malcontents, he finds a tongue he did not even know he had. When Hennebeau tries to interrupt, Maheu even cuts him short; he discovers, in every sense, the power of speech. Perhaps even more striking is the finding of a voice by Bonnemort on the night of moon-madness. Bonnemort finds a language partly inarticulate and incoherent, but which speaks profoundly of years of misery and privation.

The long, confused reiteration of old woes both personal and collective from Bonnemort seems the very essence of the long, inarticulate resentment accumulated over generations by the miners and their families. Bonnemort plays here an almost hallucinatory and hypnotic role as the spectral spokes- man for the voiceless; his speech may be partly incoherent, but he speaks nevertheless to the miners’ blood and their nerve-ends, and beyond them to Zola’s readers at large.

Zola’s naturalism, with its emphasis on integrity of representation, entailed a new explicitness in the depiction of sexuality. To say less than all would be to abdicate, as Zola saw it, from the novelist’s intellectual and social function. He broke with academic convention to a degree hitherto unseen in literature. Nana, for example, represented a drastic advance toward erotic verisimilitude. The novel’s opening scene dramatises this stripping away of cultural shields as Nana appears with progressively less clothing on the stage of a theatre that its director insists is a brothel. When she finally appears naked, the power of her sexuality is such that she reduces her audience to a single mass of lusting, panting flesh.

Zola’s social and sexual themes intersect at many points. In his sexual themes he ironically subverts the notion that bourgeois supremacy over the workers is a natural rather than a cultural phenomenon. His description of the secret adultery of Mme Hennebeau with her nephew, the engineer Négrel, exposes as myth the bourgeois supposition that they, unlike the workers, are above nature – that they are able to control their natural instincts and that their social supremacy is therefore justified. Hennebeau is at first enraged when he discovers that his wife is sleeping with her nephew; but he quickly decides to turn a blind eye to her infidelity, reflecting that it is better to be cuckolded by his bourgeois nephew than by his proletarian coachman. Adultery among the bourgeoisie was much more significant than among the working class because, as transgressors of their own law, the bourgeoisie put at risk an order of civilisation structured precisely to sustain their own privileged position. The more searchingly and explicitly Zola investigated the theme of adultery, the more he risked uncovering the arbitrariness and fragility of the whole bourgeois social order.

In Pot Luck, Zola lifted the lid on the realities of bourgeois mores, exposing the hypocrisy of the dominant class, who are no more able to control their natural instincts than the workers but are simply more able at dissimulating. The bourgeois go to extreme lengths to maintain the segregation between themselves and the lower classes, whom they insistently portray as dirty, immoral, promiscuous, stupid – at best a lesser type of human, at worst some kind of wild beast. But class difference is shown to be merely a matter of money and power, tenuously holding down the raging forces of sexuality and corruption beneath the surface. What we are left with is a melting-pot, a stew, an undifferentiated world where no clear boundaries remain.

The subversive qualities of Zola’s writings are clear. He broke taboos. His work was deemed scandalous in both form and content. At every stage of his life he was involved in controversy: as a journalist, he championed Manet and the Impressionists against the upholders of academic art; he was an outspoken critic of the Second Empire régime, and he attacked the stuffy moral conservatism of the early years of the Third Republic. As a novelist, he founded the naturalist school in opposition to ‘polite’ literature: there was the scandal of L’Assommoir, the provocation of Nana, the warning of Germinal (‘Hasten to be just, or else disaster looms, the earth will open up beneath our feet’), the uncompromising candour of Earth, and the sustained critique of organised religion in Les Trois Villes (The Three Cities, 1894–98). His whole career, in his fiction as well as in his essays and pamphlets, was punctuated by attacks on the bourgeoisie. The last line of The Belly of Paris is: ‘What bastards respectable people really are!’ Zola never stopped being a danger to the established order. In 1898 he crowned his literary career with a political act, the famous open letter (‘J’accuse’) to the President of the Republic in defence of Dreyfus – a frontal attack on state power.

The Dreyfus Affair provided a logical conclusion to Zola’s career. His humanitarian vision and his compassion for the disinherited naturally allied him with all those who fought for truth and justice. He was consciously, and increasingly, a public writer. Squarely in the tradition of Voltaire and Hugo, and anticipating the work of writers like Sartre and Camus in the twentieth century, his courageous stand showed the public writer at his best. In 1893 a Jewish army officer, Alfred Dreyfus, had been accused of spying for Germany. He had been court-martialled, found guilty of treason, and sentenced to life imprisonment on Devil’s Island, off the coast of French Guiana. Despite clear evidence that emerged in 1897 showing that Dreyfus had been the victim of a fraud, the original verdict was upheld, to the outrage of Zola and his fellow Dreyfusards. By the time of ‘J’accuse’, French public opinion was polarised, not simply on the particular question of Dreyfus’s innocence or guilt but on the future of the Republic itself. The Affair magnified and brought into question the fault-lines and divisions of the Third Republic and its major institutions. The clash of republicanism and anti-republicanism, clericalism and anticlericalism, reaction and social reform, blind patriotism and rational criticism was whipped up further by xenophobia and anti-Semitism.

The role Zola played in the Dreyfus Affair invites reflection on what it meant to be a public intellectual in late nineteenth-century France. The word ‘intellectual’ itself was a pejorative term first used by the anti-revisionist press: the Dreyfusards were the first official ‘intellectuals’. To be an ‘intellectual’ meant speaking out in the name of justice; and for Zola to speak of justice was to speak in the name of the Republic. Zola’s key strategy in his address to the jury at the time of his own trial for libel in connection with the publication of ‘J’accuse’ was to present the unjust condemnation of Dreyfus as an aberration from the true Republic of 1789 and its principles of liberty and justice.

By now, gentlemen, the Dreyfus Affair is a very minor matter, very remote and very blurred, compared to the terrifying questions it has raised. There is no Dreyfus Affair any longer. There is only one issue: is France still the France of the Revolution and the Declaration of the Rights of Man, the France which gave the world liberty, and was supposed to give it justice?

Zola, condemned to imprisonment for one year, went into exile in England. The day after his sentence the League of the Rights of Man was founded, identifying the case of Dreyfus (and that of Zola) with the French Revolution, civic education, and the republican spirit.

So many currents of nineteenth-century thought and feeling circulate in Zola’s writing. His work contains many contradictory strains; indeed, part of his abiding significance is to be found in the ways in which he exemplified and articulated the contradictions of his time.

In the early days, Zola was attacked almost as much by the humanitarian left as by the conservative right, on the grounds that he painted too black a picture of the lower classes. The critical controversies surrounding the ideological impact of his working-class texts reflect ambiguities in the texts themselves. For Zola, the power of mass working-class movements was a radically new element in human history, and it aroused in him an equivocal mixture of pity and dread. L’Assommoir and Germinal create a sense of humanitarian warmth and tragic pathos in their portrayal of the downtrodden, but Zola shows no solidarity with those who propound radical social and economic solutions. As a strike leader in Germinal, Étienne Lantier becomes a demagogue, an apostle of destruction unable to contain or control the repressed energies of the strikers once they are unleashed. The Commune, in La Débâcle, is seen not as the legitimate manifestation of an urge toward equality and autonomy, but as an aberration, a further symptom of the incurable malady which infected the body politic of the recently deceased Second Empire.

In his treatment of sex and marriage, Zola broke the mould of Victorian moral cant; but he also admired what he saw as the bourgeois family ideal. The bête noire of the bourgeoisie, he was also a moralist who believed deeply in the traditional bourgeois virtues of self-discipline, hard work and moderation. Although the champion of the oppressed, he was an advocate of responsible bourgeois leadership. His biting attacks on callous greed and exploitation do not lead him to revolutionary socialism but to trust in an evolution towards a more moral, less class-ridden order, to be built, precisely, on the creative energy of the bourgeoisie. A vision of bourgeois paternalism is explicit in the last, highly didactic novels, particularly in Travail (Work, 1903), where a bourgeois Messiah creates a sentimental Utopia in which all problems have been dissolved and all classes live in harmony.

In September 1902 Zola was working on Vérité (Truth), a fictionalised account of the Dreyfus Affair, when he died, poisoned by carbon monoxide fumes from a blocked chimney. It was discovered that the chimney had been capped during repair work. Rumours of foul play, based on the many death-threats the writer had received, seem to have been borne out by revelations made in the French press in 1953. Zola, it has been suggested, was murdered by an ill-wisher who blocked up his chimney flue one day and unblocked it the following morning. Did Zola pay with his life for his belief in the truth? We cannot know. We do know, however, that on 5 October 1902 fifty thousand people turned out for his funeral, including a delegation of miners from Anzin, who came all the way to Paris and chanted ‘Germinal! Germinal! Germinal!’ as they followed his hearse through the streets of Paris.

Suggestions for further reading

Erich Auerbach, Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature, trans. Willard C. Trask, Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1953.

David Baguley (ed.), Critical Essays on Émile Zola, Boston: G.K. Hall & Co., 1986.

David Baguley, Naturalist Fiction: The Entropic Vision, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

Harold Bloom (ed.), Émile Zola, New York: Chelsea House, 2004.

Frederick Brown, Zola: A Life, New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1995.

F.W.J. Hemmings, Émile Zola, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1966.

F.W.J. Hemmings, The Life and Times of Émile Zola, London: Paul Elek, 1977.

Robert Lethbridge and Terry Keefe (eds), Zola and the Craft of Fiction, London: Leicester University Press, 1990.

Brian Nelson, Zola and the Bourgeoisie, London: Macmillan, 1983.

Angus Wilson, Émile Zola: An Introductory Study of His Novels, London: Secker and Warburg, 1964.

All twenty novels in the Rougon-Macquart cycle have been translated into English, and the principal ones are available in Oxford World’s Classics and Penguin Classics.

Comments powered by CComment