- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The scope of this novel could hardly be more ambitious. It ranges from the landing ten thousand years ago of prehistoric men in primitive rafts on the shores of what would one day be known as the Kimberley, to the apparition of a young asylum seeker off a leaky, sinking boat in roughly the same locality during the present inhospitable times. In other words, it meets the challenge of major issues both immemorial and contemporary.

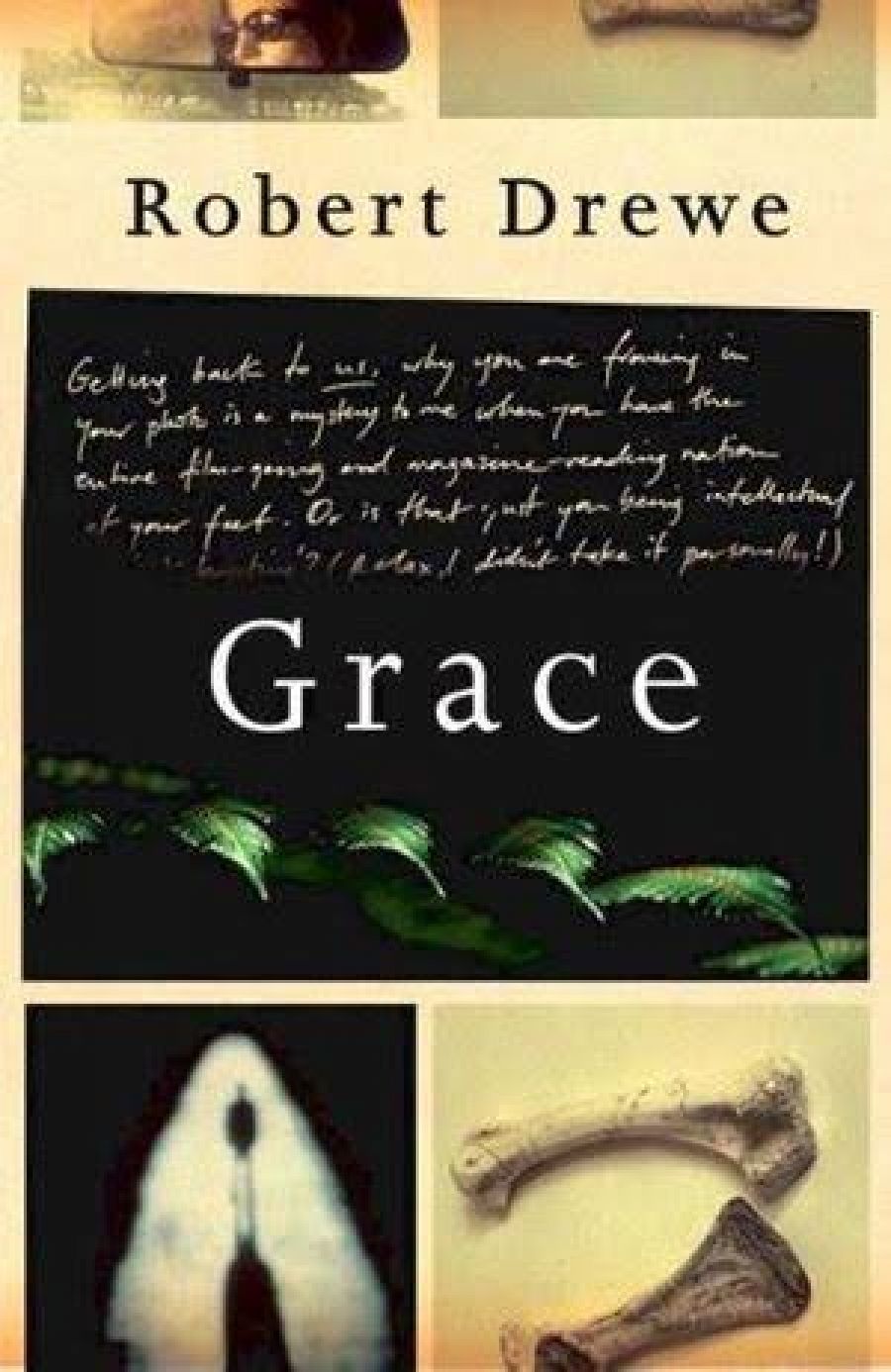

- Book 1 Title: Grace

- Book 1 Biblio: Viking, $45 hb, 415 pp, 0 670 88668 8

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/DPo2d

Molloy himself stands for another kind of arrival, an orphaned English boy ‘sent out’ to be brought up in an Anglican institution. His youthful professional reputation is made when he discovers the gracile skeleton of a small, slight girl whose age he puts simultaneously at twenty-six and sixty thousand years. To the anthropological community, she is known as Salt End Woman, but Molloy calls her Grace and names his only daughter after her.

Grace Molloy, at twenty-nine, also turns up in the Kimberley, desperate to escape from the terrifying attentions of a stalker. In Sydney, she had been a film reviewer, then, briefly, a ‘mud-crawler’, someone paid to trawl websites and report pornography. Fleeing to the edge of civilisation, she takes a job as an attendant and tour guide in a wildlife park that specialises in saltwater crocodiles (that is, the man-eating kind) and ecotourism.

Out one day finding crabs for a quartet of schoolteachers, Grace stumbles upon the asylum seeker, who has escaped, wild and starving, from detention. She hands him over to compassionate Sister Joseph, already experienced with refugees from East Timor. However, sightings of the stalker, combined with rumours that the authorities are after the boy, lead Grace to bundle him into a car and drive off. No more can be revealed without giving away the plot, but it all leads to a questioning of the grand theme of the novel: the dubious image of our island-continent as a place of refuge for people of all epochs, whether they arrive in rafts, ocean liners or leaky fishing vessels. Some, like the adventure-park tourists, arrive in jet planes, but these are self-righteous braggarts who take it upon themselves to stone goannas to death because they steal turtle eggs. Fortunately, this lot do not stay around for long. More disturbing are some of the genuine inhabitants: the authorities who allow, or perhaps arrange for, boats to sink, in order to discourage people-smuggling, and who stand by impervious while detainees go on hunger strike. In the Rousseauesque divide of the novel’s intellectual structure, the goannas, crocodiles and even the mangrove mud are amoral aspects of uncorrupted nature; the stalker, the tourists, the authorities and the slime on the web are the products of civilised society.

Has it then been downhill all the way since the primeval times when Salt End Woman walked the land? Not altogether. The later, accidental unearthing of another skeleton, thanks to a cyclone, shows that some enlightenment has been achieved. It is now taken for granted that this new one should be handed over to the Aboriginal people, who justify this trust by showing that they alone can deduce where Salt End Man would have originally stepped ashore. I will leave readers to discover whether John Molloy also redeems himself. To do so would involve opting out of the international debate that rages in the pages of Nature magazine over the true age of Salt End Woman (John’s estimate is now cheekily upped to one hundred thousand years) and relinquishing ‘his’ skeleton also to Aboriginal custody.

The themes of this novel sweepingly touch upon: evolution and genetics; anthropology and ecotourism; conspiracy theory and detention policy; boat people and stalkers. The human interplay includes a good deal about loss, betrayal and the strength of vertical (parental, filial) rather than radial relationships.

Yet the overarching story is broken up into many small facets that touch on a number of smaller, human details, such as Molloy’s truncated relationship with Grace’s mother, Grace’s passion for films of the 1970s, and the boy’s obsession with Leonardo di Caprio in the movie Titanic. Every now and then, important nuggets of past information are conveyed through a somewhat arbitrary switch in point of view, resulting in awkward changes of voice inconsistent with the tonal nuances of the omniscient narrator.

This is not the major flaw, however. Drewe, unfortunately, seems to feel it necessary to inject some light relief, which takes the form of targeting groups of individuals whom he intends to satirise but succeeds only in patronising. Among these unfortunates are the baby boomers, reduced to practising yogalates – ‘that cross between yoga and Pilates that sounded like some new low-fat dessert’ – and the ‘Grey Wanderers’ – ‘so bloody jolly … In company the wives behaved as if the men were invisible. “He’ll eat anything you put before him. Absolutely anything.” “Oh yes, so will mine …”’

This is an admirable novel, long enough to have benefited from a few judicious cuts; the tacky jibes and banal dialogue strike false notes in good writing conveying a vivid sense of landscape and empathetic main characters.

Comments powered by CComment