- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Custom Article Title: James Ley reviews 'The Lost Thoughts of Soldiers' by Delia Falconer

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

It is eight years since Delia Falconer published her successful début novel, The Service of Clouds. Eight years is a long time. It took James Joyce eight years to write Ulysses (1922). Eight years is one year longer than Joseph Heller laboured over Catch-22 (1961) and about six years longer than it took George Eliot to knock out Middlemarch (1871-72).

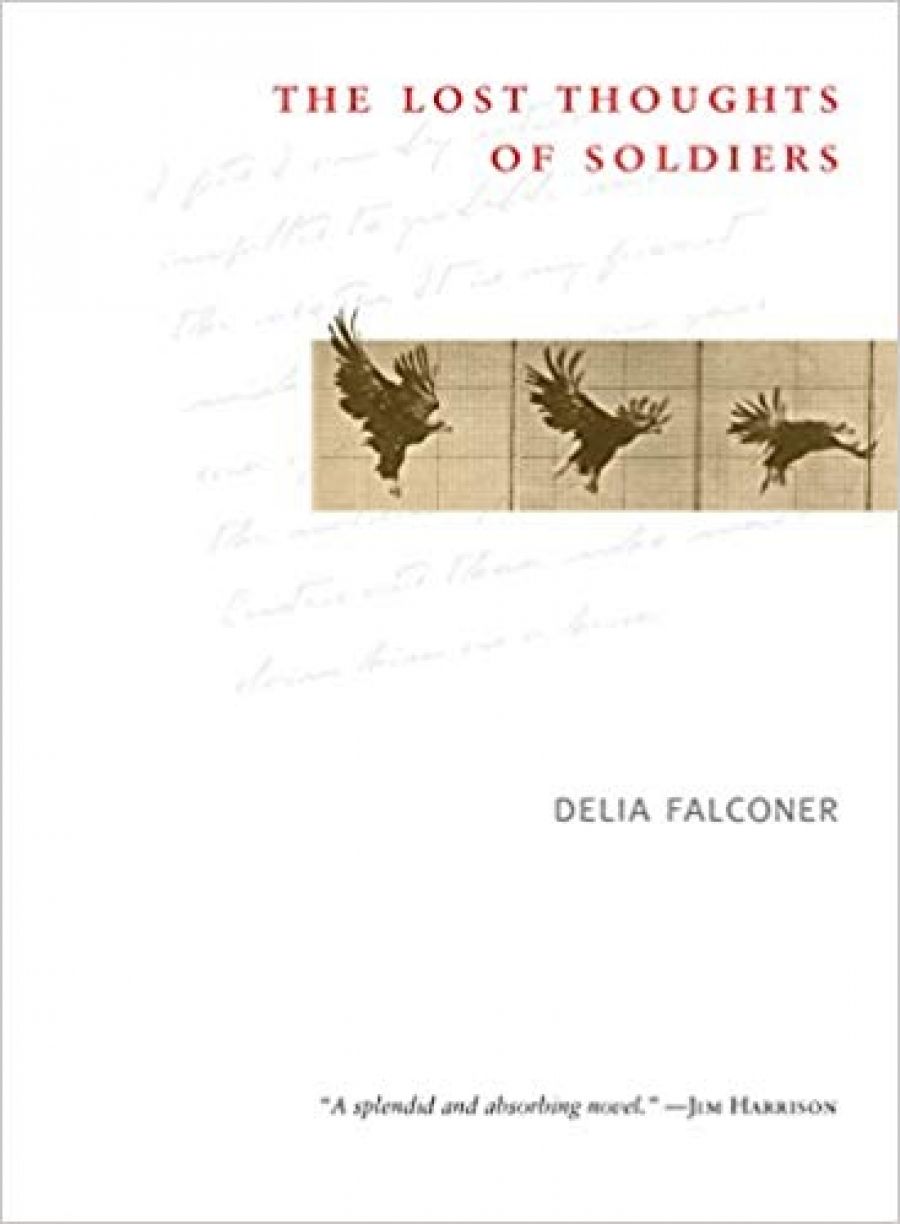

- Book 1 Title: The Lost Thoughts of Soldiers

- Book 1 Biblio: Picador $28 pb, 146 pp, 0330421794

The Lost Thoughts of Soldiers is another matter entirely. It is superior to The Service of Clouds in every way. In fact, aside from the occasional sententious phrase and the fact that silver is still her favourite colour, it is almost unrecognisable as the work of the same author. In sharp contrast to her overwritten début, Lost Thoughts is lean and effective – an arresting example of a writer saying more with less. We now know what Delia Falconer has been doing for eight years: she has been crossing things out.

The book is loosely based on the experiences of Frederick Benteen, who served in the US Army under the ill-fated General Custer but survived the disastrous 1876 battle at Little Bighorn. The moody opening pages find an aged Benteen shuffling through his retirement, his life tainted by a vague sense of melancholy. When he receives a letter from an ambitious young author wanting to write a book refuting the accusation that his actions were responsible for Custer’s demise, Benteen is prompted to call up those few scraps of memory he still possesses from the weeks preceding the battle.

A deliberately elliptical work, The Lost Thoughts of Soldiers does not fit the usual mould of an historical novel. It is less concerned with recreating a decisive moment of history than with what it feels like to be inside that moment. Benteen’s fragmented recollections focus on the day-to-day lives of the soldiers as a kind of determinedly subjective response to the grand narrative in which he was an unwitting participant. There is a tangibility to the small details that chafes against the retrospective mythology of history, and one of the book’s real achievements is the ease with which it inhabits the masculine milieu of Custer’s soldiers. The depiction of the men’s interaction, the way the subtext of their coarse jokes hints at the pressures they face, is admirably understated, raising questions about the psychology of warfare and, more generally, about masculinity itself. Along the way, the novel also opens up an interesting, if tentative, investigation into the nationalist myth-making of the United States, drawing upon a particular strand of restless, metaphysical writing that runs through American literature from Herman Melville to Cormac McCarthy.

That such a succinct book is able to evoke such a rich combination of themes is a tribute to the economy with which it is written. But the novel’s most impressive feature is its lightness of touch, its capacity to bring its characters to life with a few deft strokes. Consider, for example, this concise portrait of Custer’s wife:

They hated her, though – Libbie Custer.

That crimped ambitious mouth, those little teeth. Her eyes filled with a dark hunger, so that she later learned to twist her head in photographs to hide it.

She turned each sentence with an irony so precisely obscurative that she made it a kind of game to find her out within it. Is that a fact? Do you think so, now? Her face a mask of comic wisdom until you wondered if anyone ever had a true opinion on this earth.

Brilliant. A handful of crisp sentences and Libbie Custer’s personality is prised open like a clam shell. Everything is conveyed in a few perfectly observed details: her vanity, her unattractiveness, her calculating ambition; the coquettishness that speaks of her disdain for the men under her husband’s command. The soldiers hate Libbie Custer, and in less than a hundred words you understand why. There is even the authentic lilt of frontier vernacular in the delicate syntax of that final sentence, and in the carefully chosen word ‘obscurative’.

Falconer has always been a fastidious writer. In the past, this has tended to give even her most lavish prose a slightly starched quality. In The Lost Thoughts of Soldiers, however, the tone is relaxed without sacrificing any of her usual precision. The subtlety with which the narrative indirectly inhabits Benteen’s consciousness and the sensitivity with which it depicts the relationship between Benteen and his wife Frabbie are impressive. At its best, the book is a vindication of Falconer’s dedication to the craft of writing. It was eight years well spent.

Comments powered by CComment