- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

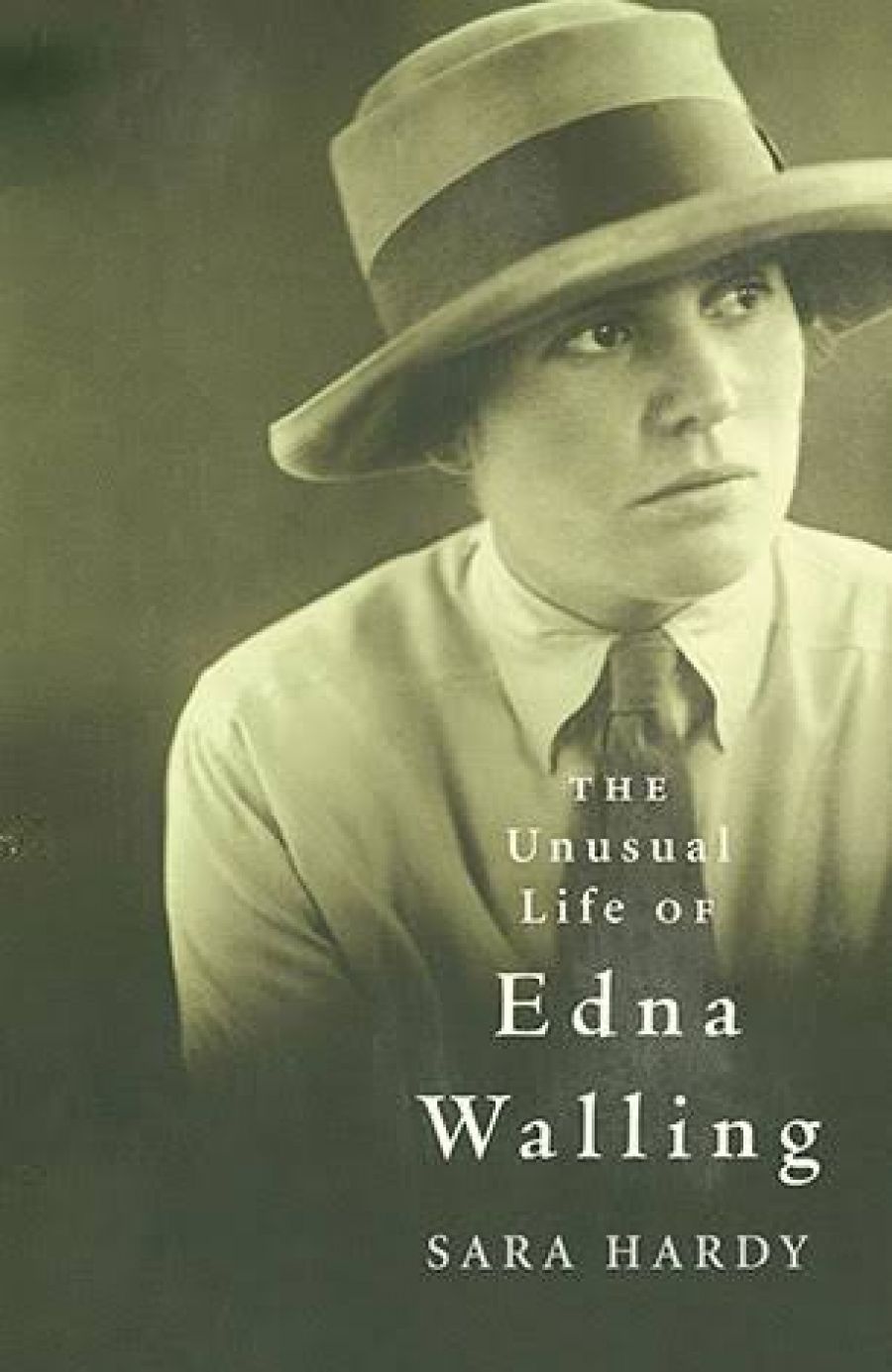

Much has been written on Edna Walling’s gardens, first by herself, later by garden historians, although no detailed account of her early career has been attempted, and less still is generally known of her private life. With a play on Walling to her credit (1987), Sara Hardy presents an account of her private life (1895–1973) and of her early career.

- Book 1 Title: The Unusual Life Of Edna Walling

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $29.95 pb, 304 pp, 1 74114 229 6

Fire, which was to mark Walling’s life, destroyed her family’s shop and house. The family migrated first to New Zealand, then to Melbourne, where her father prospered as an import agent. Walling never saw England again, but carried it in her imagination. Two false starts as a station hand and nurse led her to the Burnley School of Horticulture, where she completed a two-year diploma without showing great enthusiasm for gardening itself; nor were the next few years as a jobbing gardener any more uplifting.

Walling’s moment of illumination occurred when she noticed a stone wall and began to sense the possibilities of garden design. How she educated herself as a designer is still unclear; she rarely acknowledged the influence of William Robinson, Gertrude Jekyll, Edwin Lutyens, Reginald Blomfield, the Arts and Crafts Movement, and the formal Italian landscape, although all these and more manifest themselves in her work. The airy lack of candour is puzzling. But then, Walling, as Hardy admits, was an elusive person. Elusive, difficult, dominating – no half measures. Hardy, to her credit, allows rivals and critics to have their say. The emphasis, naturally, is on those relations, friends and assistants who supported her, put her financial affairs in order, laboured physically or advised her on her books. A determined redhead, Walling grew into a physically strong young woman. She was not domestically inclined, and the régime at Sonning, her Mooroolbark cottage, sounds spartan; much of the cottage was built of recycled material; but her clothes were laid out for her, and usually her meals cooked for her. She had a room of her own; the assistant lived in a rough shed.

The Mooroolbark settlement, Bickleigh Vale, was not only an early experiment in orderly development (Walling held a covenant on land sold and the buildings erected); it was also, for many years, a largely female settlement. Victoria in the 1920s saw a flowering of emancipated, middle-class women, but one senses that most who set up house merged into the landscape. Not that Walling challenged the conventions; but in her jodhpurs, shirt and tie, and sensible hat, she cut a figure which even the doziest of Mooroolbark natives could not ignore. Relations seem to have been good, though Walling drew the line at pig farmers for neighbours.

Hardy discusses her friendships with women in an easy, sympathetic manner, and her biography is, in one sense, a study in the variety of friendship. Evidence survives for only one intense relationship: a private letter meant only for the other party reveals a vulnerable side to Walling’s dominant personality. This is Radclyffe Hall country, whereas other correspondence suggests the cheerier world of E.F. Benson’s Mapp and Lucia. Hardy suggests that Walling was a lonely woman whose main passion was poured into her work and whose consolation was her music and her pets.

In her work, Walling linked two worlds: designing formal gardens for mansions or country houses (Nellie Melba was an early client); and, through her journalism and later her books, advising middle-class gardeners on informal designs and planting. Her sensibilities, evoking memories of a softer English landscape, appealed to a generation which had seen war destroy the old certainties, and which yearned for stability, simple comfort, and greenness in an often drought-ridden country. It is no surprise that Gardening in Australia (1943) should have been reprinted twice, offering consolation to another war generation.

By the 1950s Walling was deploring the spread of suburbia and the destruction of the landscape. Her last book, The Australian Roadside (1952), was a protest against crass destruction. Her interest in native flora increased as it became more threatened. Times were changing, as were fashions and priorities. Editors began to question her journalism as dated; publishers rejected her manuscripts. Walling grew restless and thought of moving to Queensland. Her last years were spent at Buderim, in Queensland, where she died. Within five years of her death, she became a beneficiary of the new garden history movement, and her reputation, previously somewhat in eclipse, was restored by younger enthusiasts. Experts agree that she has had a fundamental and lasting influence on garden design. She is also seen as a pioneer of environmentalism: a link between the frugal 1930s and the 1990s.

Walling is a tricky subject for a full-scale pioneer biography. Her early papers and memorabilia were destroyed in the fire that razed her first cottage to the ground in 1935; more papers and photographs were thrown out when she moved to Queensland. Most of her friends and clients are dead, although her niece has provided a valuable link with another age. Presumably in response to lacunae, Hardy intersperses the lively narrative with recreated pieces, describing scenes or events. The limitation of this technique is demonstrated on pages 60–69, as Walling takes the first vital steps in her career. More detail is needed here, of the sort to be found in the informative but unindexed endnotes. Readers are advised to refer to them as they move through the chapters.

With the evidence of a private life meagre, possibly more could have been made of the influences on her work: the writers and designers in England; the Melbourne of the 1920s and 1930s, especially the women of that period; the range of clients and her relations with them (Walling’s passage of arms with an equally determined pastoralist provides an entertaining cameo); and above all, the loyal middle-class readers who had her books on their shelves and whose tastes coincided with hers – people who stuck by her ideas despite the vagaries of fashion, because she provided an unfussy, informal recollection of ancestral memories and home.

Such a book would have entailed a larger scale of biography, of the sort so splendidly achieved by Hilary Spurling in her lives of Ivy Compton-Burnett and Paul Scott. The publishers probably did not want this. What Hardy has done, and done effectively, is to gather together at the eleventh hour as much on Walling’s private life as evidence and reticence will allow, and for this readers will be grateful. Hardy writes in a direct, informal style with a breeziness that captures something of the 1920s mood, the pause between Great War and the Depression.

And with the passage of time, as Walling’s last gardens change or are destroyed, her books, and the photographs especially, will remain lasting evidence of a moment in the life of middle-class Australia and a moment in the history of Australia’s landscapes.

Comments powered by CComment