- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

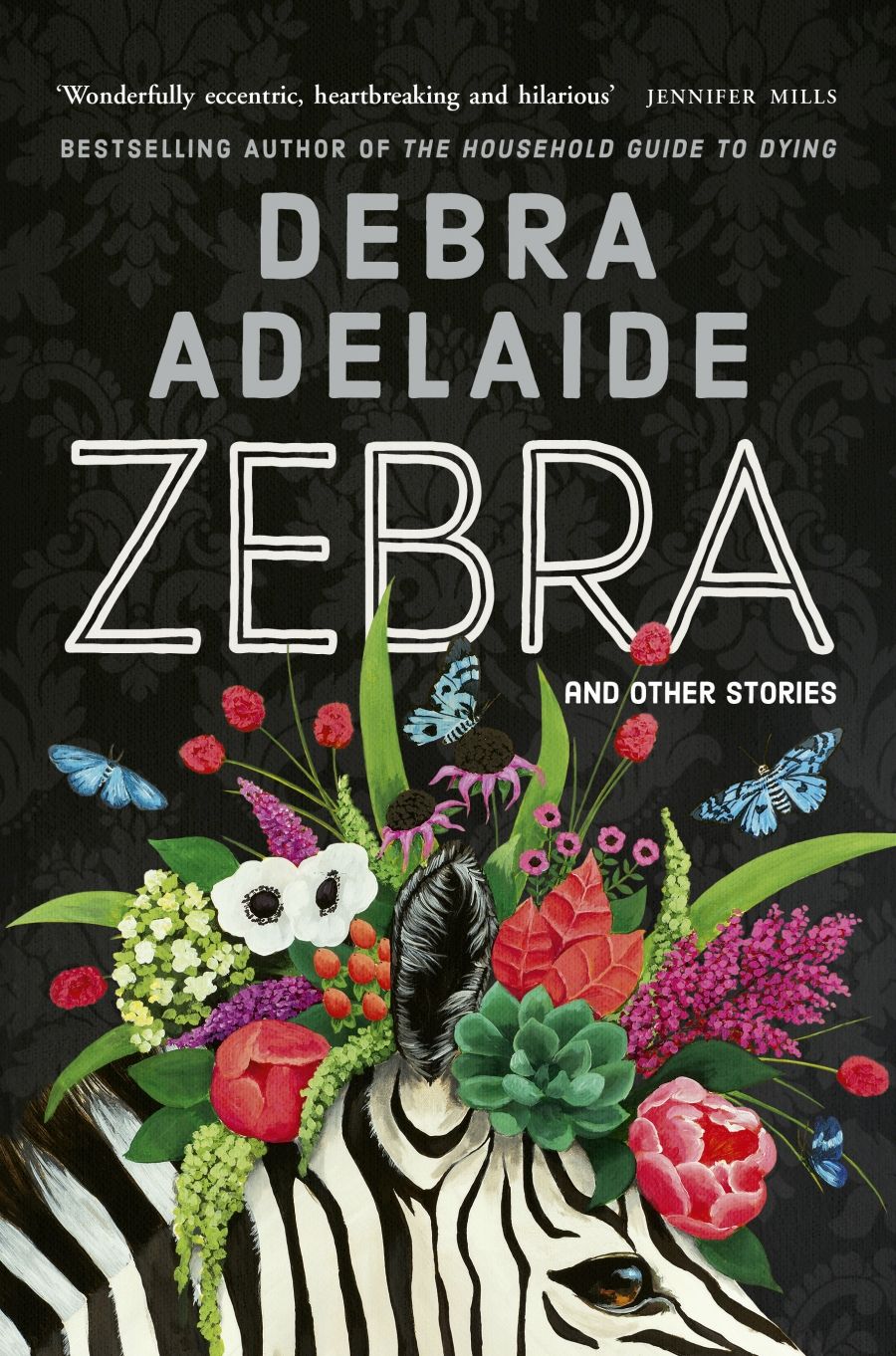

- Custom Article Title: David Haworth reviews <em>Zebra & other Stories</em> by Debra Adelaide

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

As the United States tears itself to pieces over a proposed wall, which has in recent months transmogrified into a steel fence, here in Australia we have no right to be smug or to rubberneck. After all, Australia loves its fences. Since it was first occupied as a penal colony, this land has been bisected by a seemingly endless ...

- Book 1 Title: Zebra & other Stories

- Book 1 Biblio: Picador, $29.99 pb, 324 pp, 9781760781699

Adelaide, Debra (by Phillip Klaunzer, via Penguin Australia, 2018)

Adelaide, Debra (by Phillip Klaunzer, via Penguin Australia, 2018)

In ‘The Master Shavers’ Association of Paradise’, a young man detained at an island prison tries to survive by showing generosity to his fellow prisoners. In ‘I am at Home Now’, Woollarawarre Bennelong writes to the woman he once stayed with in England, thanking her for her hospitality. And in ‘Wipe Away Your Tears’, a woman visits Anzac Cove in Turkey and hears about small moments of generosity shared between the Anzacs and the Turkish forces. Over the course of the collection, a timely theme emerges. Adelaide reminds her readers that, despite these fences, trenches, barricades, and border walls – despite all the forces intended to divide people – it is still possible to show compassion.

In the final story, the eponymous ‘Zebra’, Adelaide suggests that kindness thrown over a barricade won’t cut it: the principles of being a good neighbour must be enacted both personally and at a national level. This strange and beguiling novella, comprising a third of the volume, is similar to the opening story in that it depicts a woman hanging about near her back fence. The woman happens to be prime minister, and the property in question is the Lodge. We don’t see her conduct much prime ministerial business. Rather, she pursues domestic matters: adopting a zebra from an overseas zoo; dealing with a sexist neighbour; and overseeing the construction of a children’s farm and a hedge maze. Both the titular zebra (is it black with white stripes or white with black stripes?) and the maze it wanders through are seductive symbols of ambiguity, hybridity, and liminality; they work as counterpoints to the various fences and divisions in the book. In the unashamedly idealised character of the prime minister, Adelaide depicts an elected leader who demolishes walls rather than erects them. But the novella fascinates primarily because the protagonist’s fictional world doesn’t hold together in a strictly realist way. We are given numerous details about how this politician has transformed the nation, but we only ever see her working on her gardens and her house. The personal is transmuted into wide-ranging political action, but this occurs via a mysterious, seemingly magical process:

All her housekeeping, her good order, her sensible decisions, the harmony and joy that had rippled through the rooms like the laughter of elves had extended past the house, outside the grounds, beyond the neighbourhood, through the city, and flowed past the borders, across the states, the whole country.

Readers familiar with Adelaide’s work will be aware how brilliantly she can capture the textures of everyday experience – home life, family life, the lived experience of women. This fascination with the quotidian is on full display in Zebra. But there is something new here as well. The stories in this accomplished and moving work are more fantastical than much of Adelaide’s previous work. Taken together, they exhibit a restless and ambitious desire to examine many of the core myths that Australia as a nation tells about itself – myths about our First Peoples, asylum seekers, the Anzacs, and our elected leaders.

Comments powered by CComment