- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Commentary

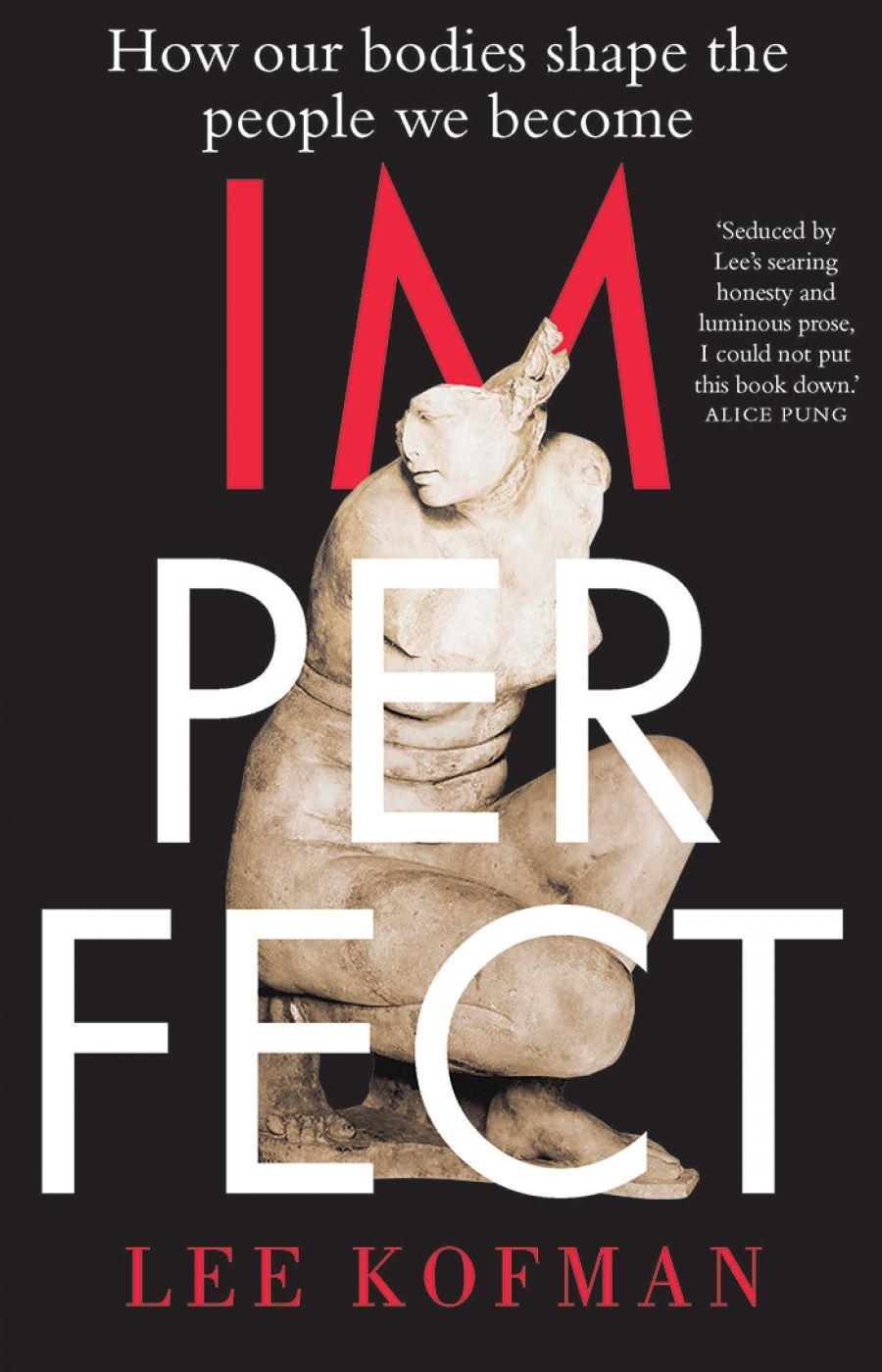

- Custom Article Title: Tali Lavi reviews <em>Imperfect: How our bodies shape the people we become</em> by Lee Kofman

- Custom Highlight Text:

A marble statue of a crouching Venus disfigured by age and circumstance appears on the cover of Lee Kofman’s Imperfect. The goddess of love and beauty is a ruin, although one capable of radiating an uncertain allure. Through a deft trick of typography, the emblazoned title can be read as either ‘Imperfect’ or ‘I’m Perfect’ ...

- Book 1 Title: Imperfect: How our bodies shape the people we become

- Book 1 Biblio: Affirm Press, $32.99 pb, 318 pp, 9781925584813

In Imperfect, the writer’s past unconventional marital lifestyle as recounted in her previous memoir, The Dangerous Bride (2014), pales in relation to evidence of her gutsy spirit. As the book bears witness, Kofman’s own body is scarred. The first marks of suffering erupt at the age of eight following a heart operation in a Soviet hospital – where ‘aesthetic skin suturing’ is perceived by surgeons as a waste of time. Thankfully, she narrowly evades being operated on by ‘the Butcher’. At the age of ten, after being hit by a bus and sewn up by like-minded surgeons, she is left with considerable scars on one leg. They have accompanied her on migrations to Israel and later to Australia, along with her stories that she has written in three languages.

While Kofman concedes that her response to these scars, in covering them, is hardly courageous behaviour, her audacity resides in her sense of drama and self-parody. This is also one of the delights of the book. Before the operation, she tells the tough children of Odessa, in ‘shamelessly melodramatic fashion’, that she might die, thus endearing herself to them. Post-accident, her child self holds court on a park bench, employing her ‘mangled leg’ as a ‘social bait’ and ‘telling and re-telling my Homerian epic to people I’d just met’. These are skills Kofman continues to excel at, spinning a tale with relish and endearing herself to people.

Imperfect takes the writer’s experience as a starting point and then departs from the interior journey to meet, with curiosity and empathy, others who have ‘imperfect’ bodies. Informed by the writer’s doctoral dissertation, it is a hybrid of cultural history and memoir. Through Kofman’s interactions, we are introduced to people who don’t fit into society’s cultural aesthetic norms. The scale of subjects is wide. There are burns victims and people with fat bodies, dwarfism, Marfan Syndrome, self-harm scars.

Kofman has a wonderfully frank voice and rejects saccharine messages that celebrate these forms without qualification, or narratives that are overarchingly triumphant. Loneliness, isolation and terrible ostracisation are darker themes. She speaks of the redeeming force of a loving partner and wonders at the price it costs to utter this in a female voice, as if it might erode her feminist positioning. Near impossible standards of female beauty, their unrelenting promotion and pursuit, are constant themes in the book. Kofman almost coquettishly professes an attraction to forms that contain beauty, and admits an aversion to its utter repudiation.

Last year, it seemed impossible to avoid the anthem of inclusivity ‘This Is Me’, a song featured on the The Greatest Showman soundtrack and sung by Keala Settle, the large bearded lady of the film. In true Hollywood manner, the lyrics move from the darker sentiment of the pariah, ‘I’ve learned to be ashamed of all my scars’ to the feel-good, ‘I’m not scared to be seen / I make no apologies, this is me.’ While not apologetic, Kofman is also not belting out a similarly uncomplicated tune of triumph and glory – one perhaps more palatable to those who wish for Hollywood trajectories.

As I was reading Imperfect, thoughts of the film recurred. Its flagrant rewriting of history makes me acutely uncomfortable. P.T. Barnum appears as a hero of, rather than a promoter of ‘freak shows’ and profiteer of a culture that equated voyeurism of human ‘oddities’ with entertainment: the same grim exploitative Victorian parading that rendered Sarah Baartman as a subhuman ‘Hottentot Venus’. Kofman’s book is the inverse of this approach, for even as the writer discloses voyeuristic tendencies, they are not the propelling force of her study.

Imperfect refers to familiar individuals, such as Lucy Grealy and Turia Pitt, alongside thinkers and cultural critics. Kofman encounters and interviews her ‘imperfect’-looking subjects – Karen Jacques, Andy Jackson, ‘Mia’, and others – not to render them strange but to explore how it is for them to be rendered strange by others. Looking and visibility are at the core of this work, as is fitting for a book dedicated to one of her sons, who has albinism and its associated condition of nystagmus (involuntary movement of the eyes), or, as the writer phrases it, ‘my boy with beautiful dancing eyes’. Kofman’s writerly gaze also dances, but in her case purposefully, from the internal to the external, defying simplistic resolutions with compassion and brio.

Comments powered by CComment