- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Commentary

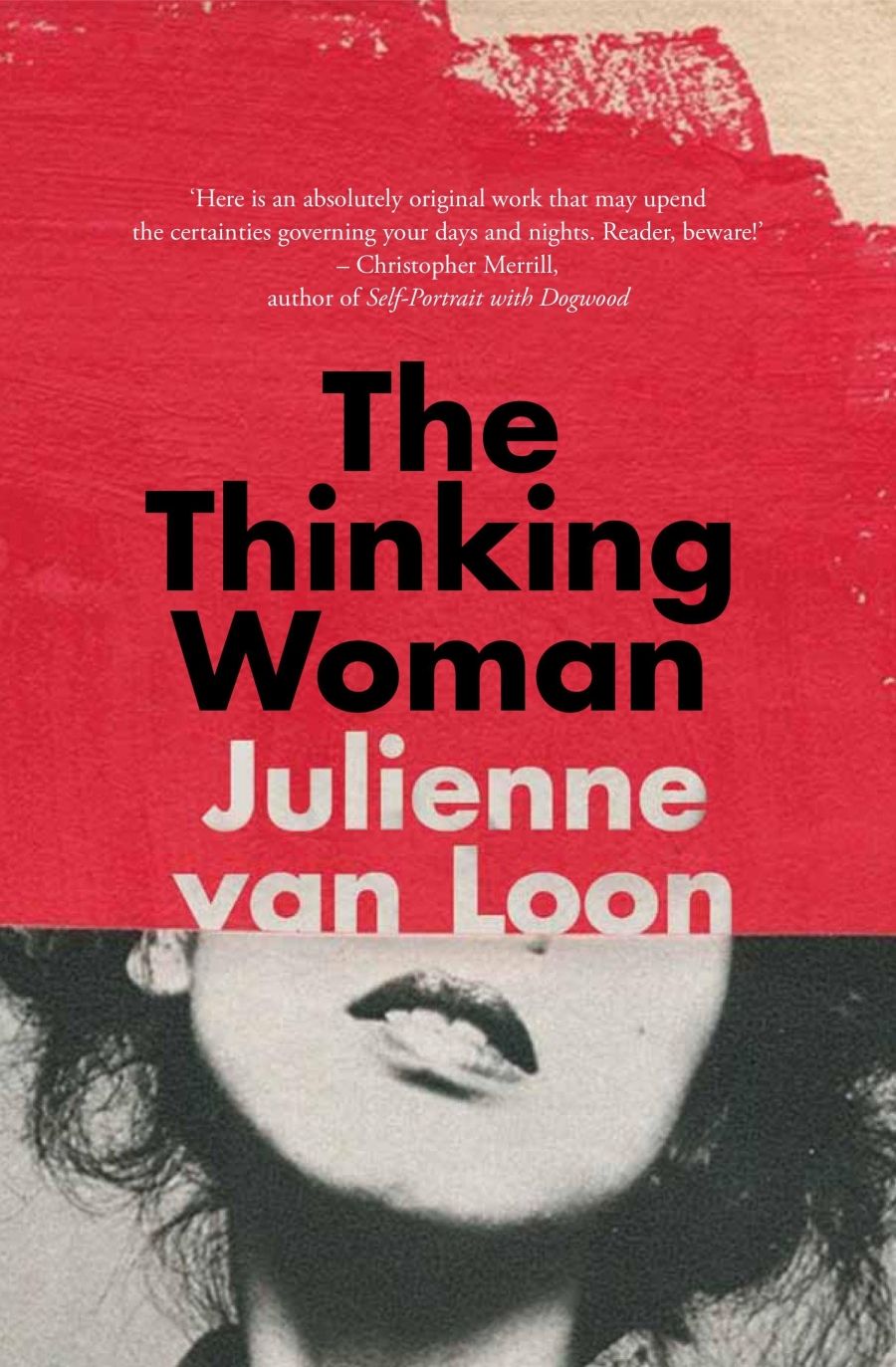

- Custom Article Title: Johanna Leggatt reviews <em>The Thinking Woman</em> by Julienne van Loon

- Custom Highlight Text:

Novelist and academic Julienne van Loon does not doubt that the thinking woman is ‘alive and well’, but when she scans the (mostly) male names in bookstore philosophy sections and the (mostly) male staff lists of university philosophy departments, she wonders where they are hiding ...

- Book 1 Title: The Thinking Woman

- Book 1 Biblio: NewSouth Publishing, $34.99 pb, 251 pp, 9781742236308

Van Loon travels to the United States and visits the Brooklyn home of writer Siri Hustvedt, where they discuss the notion of ‘play’ and its importance in fuelling the imaginative life of adults and in providing relief from the strain of navigating our inner and outer reality. Hustvedt speaks of traumatised adults who are, tragically, unable to play; they cannot respond spontaneously or imaginatively to their environment. As neuroscientist Stuart Brown asserts, the opposite of play is not labour but depression, a concretisation of ideas, and a deep rejection of the possibility of metaphor.

In the chapter on love, van Loon opens up about the end of her long-term partnership. She recounts not the fights or betrayals but the slow drifting apart of two people who are steadily falling out of love, leaving van Loon to wonder whether she is ‘trapped in the wrong narrative’. Her relationship ends not long after she discusses a novel with a colleague and, while doing so, notices something stirring, the potential for ‘profound intimacy: strange, improbable, and completely unexpected’. The story of the end of her relationship is told against the backdrop of van Loon’s meeting with US writer Laura Kipnis, who, in her book Against Love: A polemic, posits adultery as a political act that can trigger some people to wake up from the oppressive work of maintaining the domestic marriage set-up. Kipnis wonders whether the work that is required to maintain domestic coupledom is analogous to Marx’s ‘surplus labour’, a kind of interminable exertion from which we never clock off. Kipnis astutely notes how couples discipline each other, both overtly and covertly, creating cordons and limitations in otherwise free lives. Why do we stay, van Loon is prompted to wonder, when a relationship has become little more than a perfunctory nine-to-five job?

After a series of illuminating discussions with philosopher Nancy Holmstrom on the notion of employment and work, van Loon starts to question whether there is such a thing as meaningful, non-alienated labour in a post-industrial context. Van Loon doesn’t reach a definitive answer, but her explorations of our relationship to work are among the most perceptive sections of her book. After van Loon resigns from her workplace of seventeen years, she experiences a dulling epiphany of sorts. There is no formal thanks or reply to her resignation letter, no acknowledgment of a mutually beneficial joint project coming to a close. Van Loon realises there was nothing special or unique about her relationship to her employer, and the considerable value she invested was decidedly one-way. It leaves Van Loon wondering about the illusory quality of those past seventeen years and her connection to what she produced in that time: the epitome of Marx’s concept of alienated labour.

Julienne van Loon (photograph via Twitter)Van Loon also discusses ‘wonder’ with fiction writer Marina Warner, friendship with feminist and philosopher Rosi Braidotti, and exchanges emails with psychoanalyst and feminist Julia Kristeva about the notion of ‘fear’, especially women’s fear, which casts a long shadow over van Loon’s early life. Her recollections of her tough upbringing, of her long-suffering mother and abusive father, are moving, but this is not what stays with you in the end. It is van Loon’s capacity for wonder, the call of her imagination, which really moves the reader.

Julienne van Loon (photograph via Twitter)Van Loon also discusses ‘wonder’ with fiction writer Marina Warner, friendship with feminist and philosopher Rosi Braidotti, and exchanges emails with psychoanalyst and feminist Julia Kristeva about the notion of ‘fear’, especially women’s fear, which casts a long shadow over van Loon’s early life. Her recollections of her tough upbringing, of her long-suffering mother and abusive father, are moving, but this is not what stays with you in the end. It is van Loon’s capacity for wonder, the call of her imagination, which really moves the reader.

Wonder, in many respects, is the ultimate feminist ideal. A person in a state of wonderment has agency; she is the subject rather than the object of her life, sufficiently free from fear and duty to be enthralled by ideas. Wonder certainly saved van Loon from the indignities of her small double-brick house in Dubbo, with an often violent and drunk father. The more her father terrorised the home, the more van Loon sought out her own company, the inner world of her imagination: ‘Wonder nurtured me. It saw me through my bewilderment and beyond it.’ It also led to a career as a writer and thinker, for which the world of ideas is all the richer.

Comments powered by CComment