- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Matthew Flinders, arriving in Sydney in 1803 after circumnavigating Australia, wrote to his wife bemoaning ‘the dreadful havock that death is making all around’. The sailors in Peter Mews’s Bright Planet have a more phlegmatic attitude. At least twelve of the ship’s complement of sixteen fail to survive the expedition. There may be more, but death becomes an everyday occurrence hardly worth mentioning. By the end, we are not entirely sure whether the remaining characters are alive or dead.

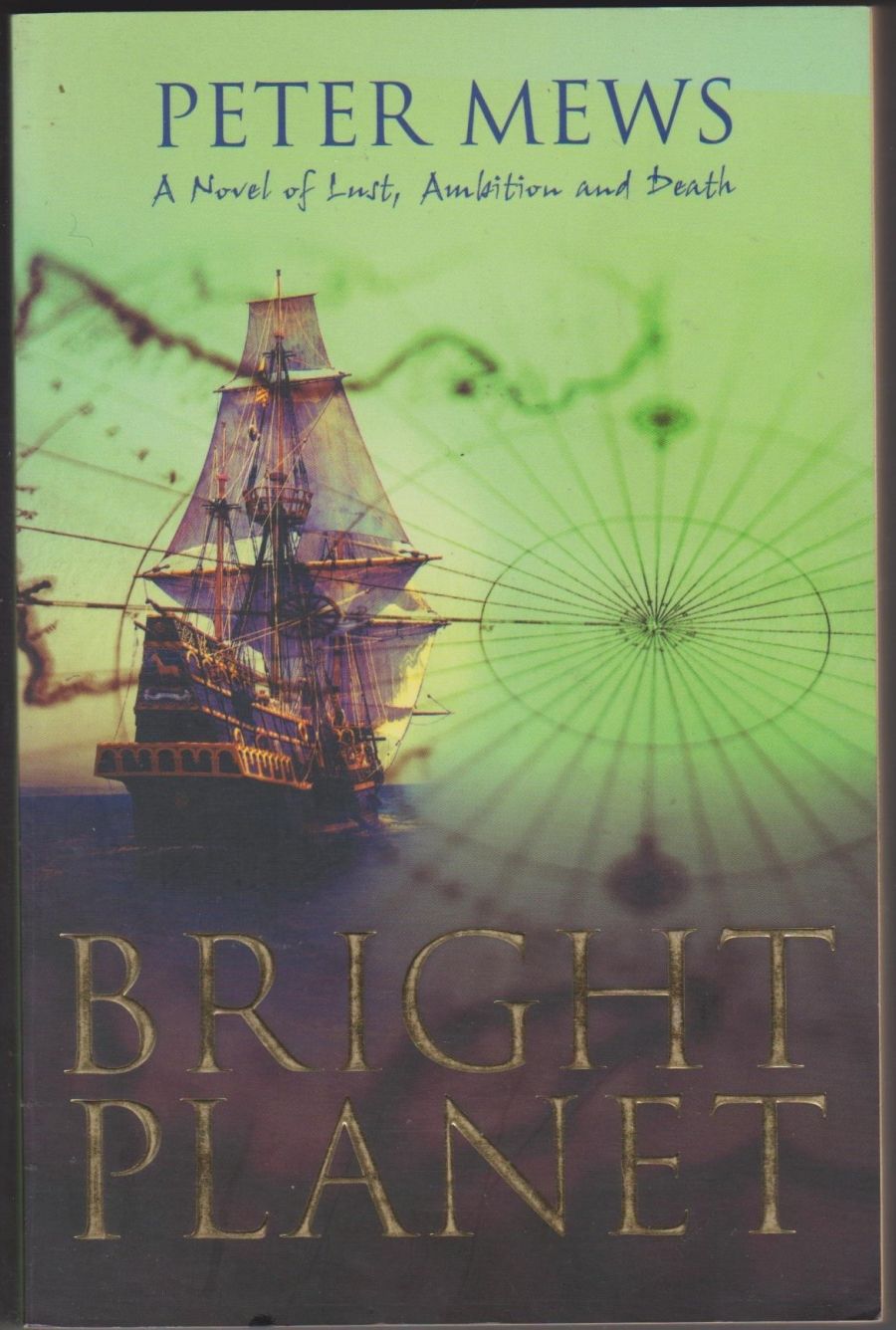

- Book 1 Title: Bright Planet

- Book 1 Biblio: Picador, $22 pb, 287 pp

Not only fact and fiction but also reality and illusion are seriously in question here. The captain, the surgeon and the scientist on this ship all dose themselves liberally with hashish, laudanum and various potent liquors, and are consequently more or less in a state of altered consciousness much of the time. Indeed, Quiet Giles, the scientist, ‘knew that his senses were deranged, of course, but only in this manner could the journey continue’.

The captain, crew (unlucky thirteen in number) and scientists stay for a short time in Bareheep, where, it must be said, the women possess a quite astonishing degree of sexual avidity, especially considering their scarcity: one might think that they would be a little more sparing with their attentions when the odds were so much in their favour. Then again, this is probably another sly indication that this is an exercise in fantasy of a peculiarly masculine variety. Buoyed by their amorous successes, though down one lieutenant who has died of snakebite, they plausibly sail Bright Planet up the Yarra. However, when they come upon another, larger river to the northeast, we are once again off the planet Earth and in the realm of imagination.

Laced through the third-person narrative are excerpts from the self-consciously romantic journal of Quiet Giles, Esq. – he has inscribed the title page of his leather-bound volume with high-sounding phrases about a ‘most remarkable year’ and ‘extraordinary events’ before writing a word. At the end of every chapter, each of which covers the events of one day, we are given a telegraphic summary of the deaths, skirmishes and activities of the previous twenty-four hours. Parody is undoubtedly part of Mews’s intention: there are at least two obvious Joycean references, as well as the more direct allusions to nineteenth-century imperial voyaging narratives. But there is also a certain depth. Perhaps the most sympathetic character is the young sailor Edwin Robins, who jumps ship at Bareheep, only to stow away again when the town becomes too hot for him. Carrying out his long-held plan to leave the ship on arrival, he finds the country so alien that he is struck ‘with a fear he had not imagined’. He discovers, however, that the natives are more friendly than his compatriots, who resent his thieving ways. He may or may not be one of the survivors.

Bright Planet is a wry, laconic book; bold, entertaining and slightly mannered. Mews’s vocabulary is vivid and his epithets at times startlingly original: the ‘sheer night’ Edwin finds himself engulfed in; the ‘itching bachelors’ in the bar at Fawkner’s Hotel; the ‘brackish suit’ worn by a publican. It is a kind of sustained exercise in bravado. Unlike Flinders, who admitted that the thought of death was ‘too painful to dwell upon’, these sailors of a later generation seem successively less rattled by each death, revelling in the increased amenities provided by the dead men’s absence – especially accommodation and clothing. It does, indeed, take the captain, Elijah Blood, some time to come to such an insensible state of mind, but eventually he becomes ‘unburdened … by his own existence, his life was a trifle, dispensable and unessential’. Giles, in his opiated state, seems almost to be seeking death. His last words in the book are ‘Now am I dead?’ – words that also occur, teasingly, in the quotation from his diary from this last day, printed at the beginning. Mews is playing games with us. That is allowed: this is not history, but highly imaginative, fantastic fiction.

Comments powered by CComment