- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Kate Finlayson’s first novel is a bumpy bronco ride, as exhilarating, confronting, and messy as the Northern Territory that she writes about so passionately. Finlayson’s protagonist, Connie, is stuck barmaiding in a rough city pub. Despite her street smarts and university degree, Connie is starting to go to the dogs along with the pub’s patrons. She decides to leave Sydney to pursue a post-adolescent obsession with Rod Ansell, the inspiration for the Crocodile Dundee films. Ansell (his real name) is hiding somewhere in the Territory, and Connie fantasises about finding him and turning him into her ideal lover, her longed-for soul mate.

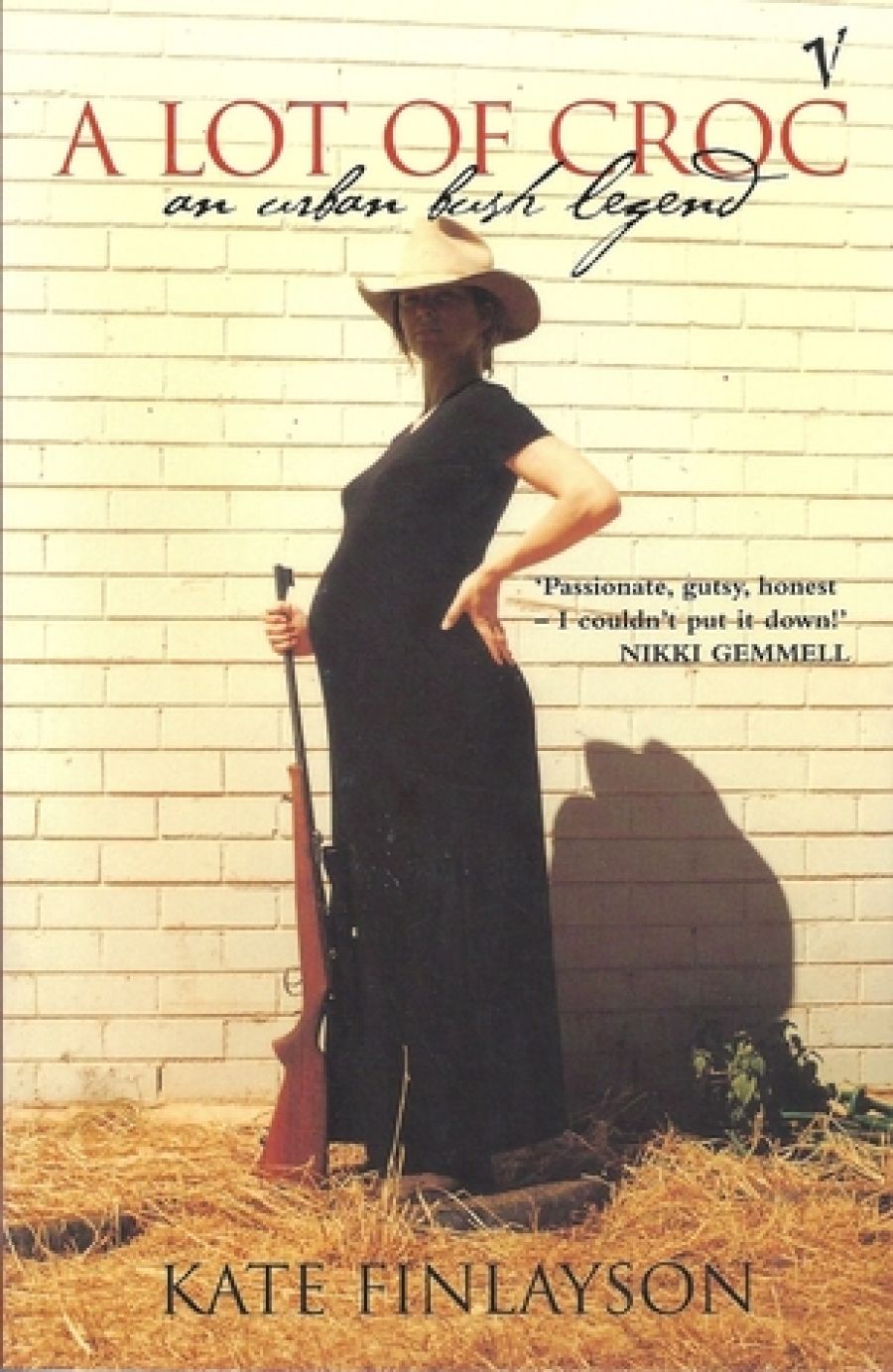

- Book 1 Title: A Lot Of Croc

- Book 1 Subtitle: An urban bush legend

- Book 1 Biblio: Vintage, $22.95 pb, 358 pp

This is the skeleton upon which is hung a rambunctious odyssey through the uglinesses and eccentricities of Top End life. Connie lands first in Alice Springs and immerses herself in fringe Aboriginal life, eager to shuck off her city ignorance. Next she finds an Aboriginal lover, but it’s not long before she’s burnt out with so much confusing cross-culturalism. She returns to barmaiding, and into the safe if hard-drinking arms of the ‘expat’ community via a white lawyer making a living from the Aboriginal industry.

Everywhere Connie goes – in the bars, in the bush – she asks people about the original ‘Crocodile Dundee’. The picture she gets is contradictory and confusing. Is Ansell a slightly crazed idealist or is he devious, dangerous, even crooked? Is he a superb old-style bushman or a fraud? Is he a true friend to Aborigines or just another white man messing with Aboriginal culture? Is the survival-among-the-crocodiles tale that made him famous even true or is the real story much less glamorous?

Connie tires of the lawyer and the incestuous expat life. She heads off to the Top End and a roving life as a radio reporter. Based in Katherine, she’s closer to Ansell territory, but no closer to getting his attention. In the meantime, she becomes a rodeo bunny and has an affair with a pastoralist who can’t believe he’s ‘going with a blackfella hugger’, while the parade of bush characters continues, along with the drinking, vomiting, hopelessness and desperation that constitute ordinary everyday Territory life.

This book’s strengths and weaknesses are on a big scale, and that alone makes Finlayson a writer worth watching. The portrait of the Territory – an utterly different universe from the Australia most of us know – is in-your-face vital and rich, if sometimes undisciplined. This is the best contemporary account of life in northwest Australia that I have read. It can be funny, too, with a frank humour that encompasses being ‘sung’ for love by an ugly old Aboriginal bloke, a natty account of an Alice Springs tattoo parlour, and some unlikely sex.

Finlayson is superb when writing about Aboriginal life. She tells it as she sees it, from a white perspective, unsentimental and wrenchingly honest, with an unpretentious empathy for what it means to live on the other side of white culture. Her depictions of the sights and smells of Aboriginal life leap off the page.

Less successful, I think, is the Crocodile Dundee tale. Ansell’s story is told almost entirely through Connie’s pub conversations with a series of eccentric characters. Long boring pub conversations are just that on the page, only more so. Endless yarns do not create a character. Until the last quarter of the book, we never meet Ansell – he is always elsewhere, always the subject of other people’s mythologising. When Connie finally catches up with him, she baulks at meeting him, afraid to confront her dream. By the time Ansell turns up, the reader no longer cares. Yet the pub conversations are not entirely wasted, as Finlayson uses them to flesh out the feel and fabric of Territory life. The Territory is a hard, nasty place where people who fit nowhere else wash up; it’s also a place of humour, endurance and true friendship. Finlayson accommodates the paradoxes with verve. We learn a lot about the Territory without it being hard work.

Connie’s personal journey towards a surer grasp of self is more problematic. She is edgy, smartarse, sexy, full of insecurities; she can be hard to like. Finlalyson’s narrative stance is a little too close to her protagonist; there is insufficient space between character, writer and reader to allow us to make up our own minds about Connie.

The central problem of the book is that it sits uneasily on the border between fiction and nonfiction. It’s a big ask to drape a fictional plot around the search for a real-life character. In plumping for fiction, Finlayson ends up with a clumsy structure and a stumbling narrative tension. But then again, could she have got away with her searing observations of Aboriginal life without the safety net that fiction affords?

The vitality of the writing makes up for a lot. There are very few young writers around with Finlayson’s gutsy ability.

Comments powered by CComment