- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Over the last couple of decades in Australia, short fiction has been a poor cousin to the literary novel. While this country continues to produce fine writers of short fiction, many of them struggle to achieve book publication of their works. Larger publishers often seem no more interested in collections of short fiction than they are in poetry collections. Their argument: short fiction, like poetry, does not sell. It has often been left to smaller Australian publishers to produce and promote short fiction writers, who are sometimes taken up by a major publisher if they achieve a notable success with a longer work.

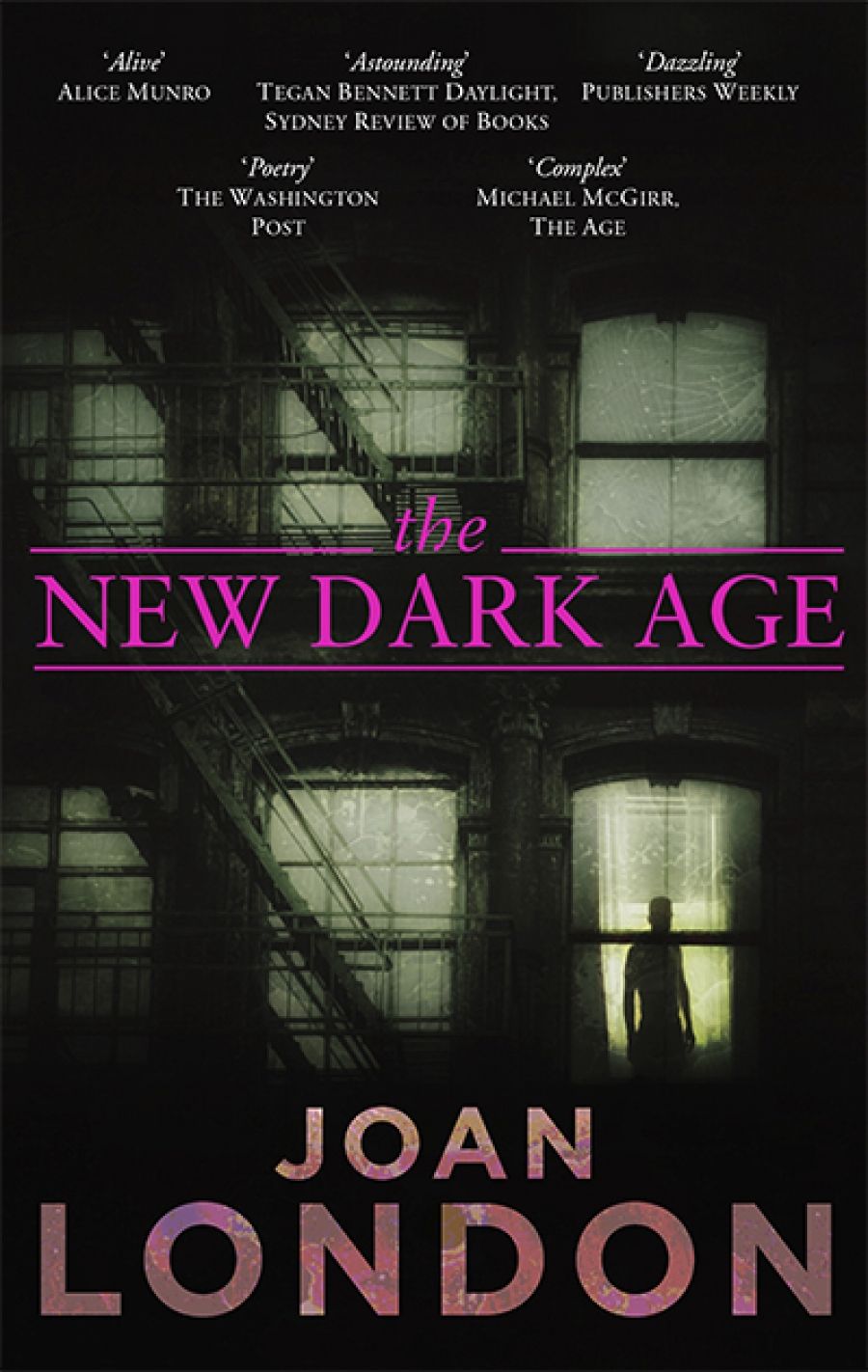

- Book 1 Title: The New Dark Age

- Book 1 Biblio: Picador, $22 pb, 353 pp

Western Australian writer Joan London’s recently released collected stories, The New Dark Age, combines most of the stories originally published in two slender volumes by Fremantle Arts Centre Press in 1986 and 1993, with two recent stories added at the end. London has received considerable attention for her novel Gilgamesh (2001), but it was as a short fiction writer that she developed and honed her craft. She is a skillful stylist, whose narratives about ordinary-seeming lives have a resonant and, at times, lyrical intensity. From the opening story in The New Dark Age, one is aware of a quiet and luminous authority. This story, ‘Sister Ships’, a minor tour de force, captures thenascent, uneasily negotiated adulthood and uncertain sexuality of young women on voyages away from home.

London is not so much interested in the consummation of relationships as in the isolation and questioning interactions of individual lives, particularly the lives of women. In three of the earlier stories in The New Dark Age, the mother of a young child finds liberation amid her uneasy domesticity; a woman visits a friend who has married, rediscovering with him an almost palpable, yet unresolved, connection; an older woman is eloquently released into the stark, troubling territory of her memory of love.

Later stories – those originally published in Letter to Constantine (1993) – extend London’s preoccupations. In the title story from this collection, London takes the reader on a meditative and mysterious journey, not so much into the heart of a relationship but around its contours, revealing a world where social and personal dislocations merge and where the reader is left to ponder what, after all, people are ever able to say about their most intimate concerns. In this, as in other stories, human experience is represented as often puzzling and, despite its lucent moments, sometimes opaque.

The penultimate story in The New Dark Age, ‘The Photographer’, reproduces two suggestive photographs by the Western Australian John Joseph Dwyer (1869–1928), who is also a character in the story. Narrated by a woman who has seen her wealthy married life utterly changed by the stock market crash of 1929, it examines how strangers brought together within a community accumulate knowledge of, represent and understand one another. Partly a meditation on history – as, more explicitly, is the story ‘Maisie Goes to India’ – it can also be read as a metaphor for London’s approach as a writer: ‘I sat him beneath the photographs I had bought from him all those years ago, of the dust storm, and the prospector, and the family riding down Hannan Street on the back of the camel. I told him how glad I was now for their detail and clarity.’ Prior to this moment, the narrator had ‘muttered something about “mystery”’ to the photographer. Mystery and clarity are two of the hallmarks of London’s fiction.

London cares about language, both its surfaces and the shifting nuances of meaning. She writes with precision and an alluring subtlety. She is observant, too, able to show things as they are; aware of the quirky, unsettling side of reality; of how large ideas inform apparently unexceptional lives. The narrator in ‘The Photographer’ says of a character in the story: ‘As a child in Perth he used to watch the trainloads of miners pass on their way from the ships of Fremantle. His mother told him they were going to the Golden Mile. His eyes shone in his long grave face. I could see he was an idealist.’ All of London’s stories make use of such economical, well-placed detail, helping her to create the sense that believable worlds lie behind her writing, however imperfectly glimpsed they may be.

In one way or another, most of the stories in this collection are about arrivals and departures; about breaking away from restraint, convention or self-censorship; about individuals trying to understand what binds and inhibits them and, where possible, attempting to free themselves. As London delves into and celebrates the mystery that lies behind the narratives that people construct of their experiences, she chronicles how difficult it is to register stable meanings. As she writes of shared understandings and of human intimacy, she shows how intimacy separates people as well as joins them.

Despite their formal and unhurried eloquence, London’s compact stories take the reader long distances. Entrancing and self-possessed, they contain a quiet kind of magic.

Comments powered by CComment