- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The great obituarist

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

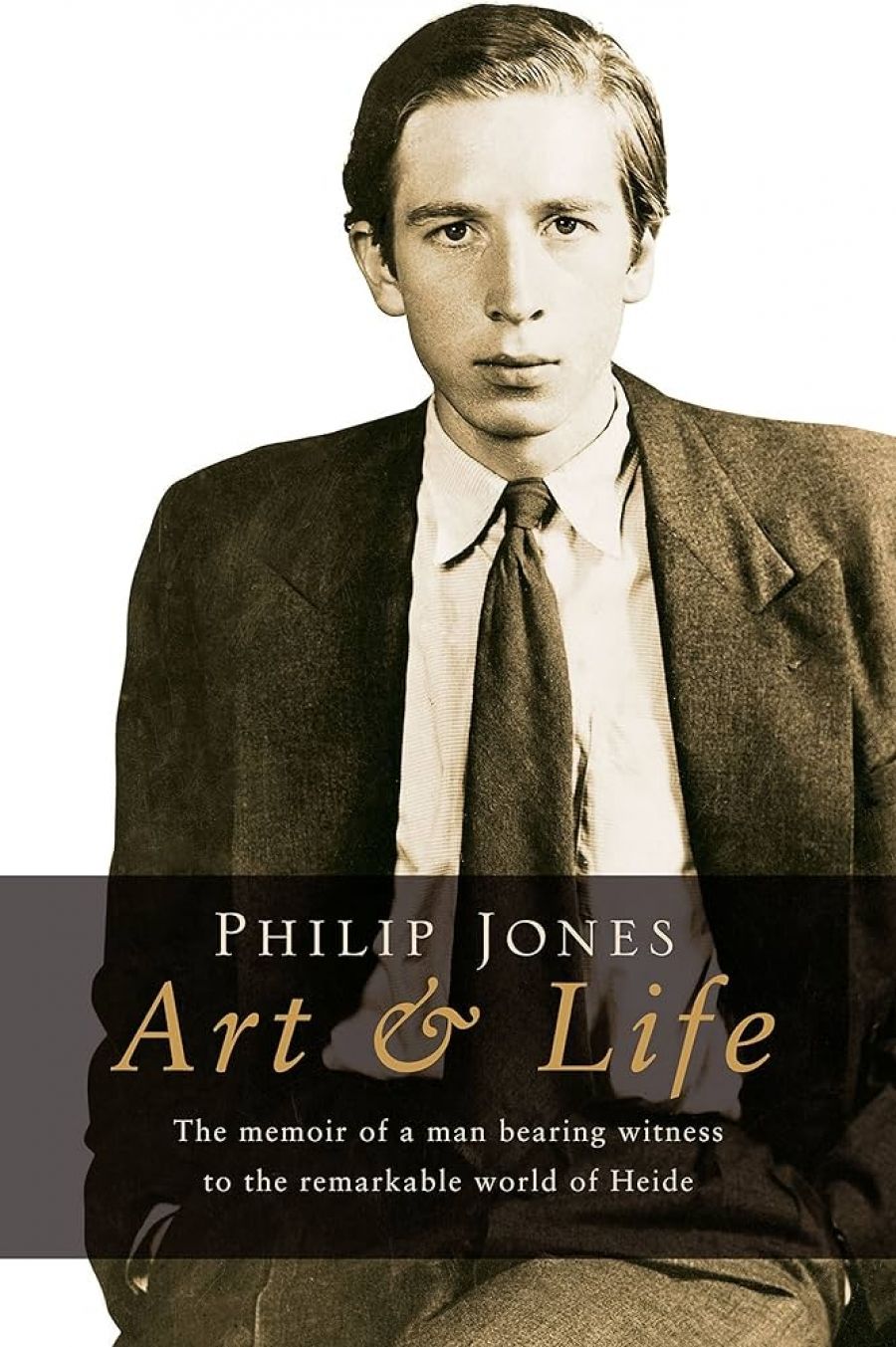

Book covers are just expensive hints, and the jacket adorning Philip Jones’s memoir of Heide and beyond is suitably suggestive. Jones may not be especially literary, but he looms at us – first youthful, now in his early seventies – as a kind of antipodean Auden: languid, floppy-tied and with searching eyes. That direct, if hooded, gaze introduces us to a soi-disant minor figure in our cultural history, but one who had an intimate place at Heide in the 1960s and 1970s, and who has known some of the authentic characters and creators in Australian art and letters.

- Book 1 Title: Art & Life

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $49.95 hb, 312 pp

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Students of recent federal elections may quibble with Philip Jones’s (and Harold Stewart’s) epigraph that ‘All Australians are anarchists at heart’, but there can be no doubt that many of their autobiographies are ringingly anarchic. Art & Life is one of them. Jones introduces us to his early life in Kerang (he was born there in 1932) and his colourful family. His father is cheerless and friendless, and young Philip soon excises him from his feelings; but his mother sounds wonderful – sharp and irreverent. One night Philip overhears them arguing about his own proclivities: ‘My mother screamed, “Of course he is not a normal boy because he does not have a normal father.”’

Soon, though, Jones, as if unable to resist, interrupts the rustic narrative with an update on his current social life: lunch at the Florentino or the Melbourne Club; the latest opening, with those interminable speeches; more radio interviews; yet another funeral. Slightly jangling at first, this constant darting about rather suits the author and produces an entertaining series of snapshots of a life.

Philip Jones has long suffered from that dubious social affliction: He Has Known Everyone. In 1952, he and his family moved to London, just in time for some of the worst peasoupers of the century. Jones joined the Q Theatre in Kew, and had coffee with Joan Collins (‘nice and chatty’). T.S. Eliot, a board member (he thinks), was often seen mooching around in the shadows. ‘I said, “Good evening, Mr Eliot,” but he did not reply.’ Such is life.

A ‘natural republican’ and ‘dyed-in-the-wool socialist’, Jones finds people more congenial in Australia, and heads home to act with Frank Thring’s Arrow Theatre and Gertrude Johnson’s (not Johnston, as in the book) National Theatre. He begins to act in radio dramas, often being cast as ‘gentlemanly men of action and leadership, including Prince Philip’. Then he meets Barrett Reid at the Public Library (now the State Library of Victoria), and his life is never the same again. Reid – poet, editor, librarian – introduces him to John and Sunday Reed at Heide, and suddenly Jones is surrounded by the art of Boyd and Perceval and Hester. Although they stay together for decades, Jones never seems wholly at ease with Reid, the consummate politician and literary figure. Movingly, Jones says this about his lover and critic: ‘Above all Barrie was a proud Australian. I think perhaps I had never met one before – at least in the cultural rather than xenophobic sense.’

Their life together seems to have been frantic as they roamed between different cities and houses, and gave huge lunches and dinners. Greenhill, one of their many homes, was a kind of open house, like their relationship. Along the way, Jones meets just about every celebrity then living or passing through Melbourne – and he hasn’t forgotten one of them. Jones befriends the Moras and lists the stars he meets at their parties (Hepburn & co.). Even glancing meetings are recorded: ‘My only recollection is of [Stravinsky’s] tiny feet encased in black shiny patent leather shoes.’ Jones describes H.V. Evatt as ‘sweet-natured’, which must be a first. Zara Holt clatters through the pages quite winningly. Robert Duncan comes to dinner and offends with his hauteur and his impromptu performance (‘I will now read a Duncan’). Jones meets Norma Major, wife of the British prime minister, and finds he has nothing in common with her – but it must go in, as in a diary, especially one intended for publication. Occasionally, the gossipy nature of the book, however qualified, seems bizarre. Of Kathleen Raine he says, ‘She fell in love with Gavin Maxwell who (it is generally believed) was gay. When their celibate relationship ended (so the story went), she cast a spell on him causing the death of his otters, a cancer diagnosis and eventually his death.’

Jones isn’t a punitive memoirist, but some of his portraits are scathing. He doesn’t take to Albert Tucker, whom he finds stuffy, too conscious of being addressed as ‘Mr Tucker’ by young artists. William Dargie he despises for his wooden art and his ‘outrageous cronyism’. He doesn’t much like Sydney, and he may not be popular in Emerald City after his dismissals of Lloyd Rees, Brett Whiteley and John Olsen.

But Hal Porter and Sidney Nolan are in a class of their own – monsters of egotism, if Jones is to be believed. He has very mixed feelings about the great memoirist (‘anti-feminist, anti-Semitic and homophobic’), though they must have been reasonably close at one point (Jones launched The Paper Chase in 1966). There is an hilarious account of a journey from Adelaide to Melbourne, with Porter in a sorry, sodden state. Jones’s perceptions of Nolan are inevitably coloured by the painter’s desertion from Heide and the breakdown of his relations with the Reeds following his marriage to Cynthia, John Reed’s sister. ‘As an artist he was a genius: as a human being, something of a psychopath.’

Jones’s loyalty to the Reeds is one of the more endearing features of this stoic but largely affectionate book. He regards them as his ‘surrogate parents’ – reshapers of the cultural climate of Australia – and remains distressed by the obloquy often heaped on them. In the 1960s he went into a bookselling business with them, and the ensuing ructions did not shake their friendship. Ultimately, the Reeds willed Heide to Jones and Barrett Reid until the second of them died.

In the 1970s and 1980s, things began to go wrong. One of their houses was destroyed in a fire, his business faltered, and Barrett Reid became ill and increasingly patronising – especially when he found himself in charge of four houses following the Reeds’ death within ten days of each other. Finally, Reid asked Jones to leave and changed the locks, dispossessing Jones, in his view. Twenty years after their separation, he still dreams of reconciliation.

Ironically, it was Reid’s death in 1995 that launched Jones on his new career as ‘Australia’s foremost obituarist’. He wrote Reid’s, moving some, scandalising others. Proud of his vault of obituaries and keen to establish his bona fides, he says: ‘I believe I am, or at least have become, a natural researcher.’ At times this chapter becomes rather surreal, as if we’re in an early Evelyn Waugh novel: Jones attends the Great Obituarists’ International Convention in New Mexico. But if you must die, Jones is clearly your man. He will find out whom you bedded, which religion you abjured and whom you had lunch with every day of your life. He even provides his own obituary, as an afterword.

The book looks fine, but there are too many factual errors. Indira Gandhi declared a state of emergency in 1975, not 1974. Patrick McCaughey is not the Director of British Art at Yale University, but he is a former Director of the Yale Center for British Art. We might overlook ‘Vida Horne’, but ‘Randolph Stowe’ (twice) is unforgivable. Jones’s style is not always felicitous (‘I once lunched with her father and he and she told me … ’). Sometimes it borders on the quaint: it’s a while since I came across ‘withal’.

As Jones states, his life has been haphazard: ‘Little was planned ahead.’ The tone of his book is admirably realistic and increasingly sure. He doesn’t look back on green pastures: ‘There were no good old days.’ And will he attend next year’s conference of the Great Obituarists in Bath? ‘Perhaps.’

Comments powered by CComment