- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Custom Article Title: Simon Caterson reviews 'Chromatopia: An illustrated history of colour' by David Coles

- Custom Highlight Text:

The story of art could be framed as a narrative of tension between the boundless creative imagination of artists and the practical limitations – including instability, scarcity, even toxicity – of their materials. As master paint-maker David Coles explains in this wonderful book ...

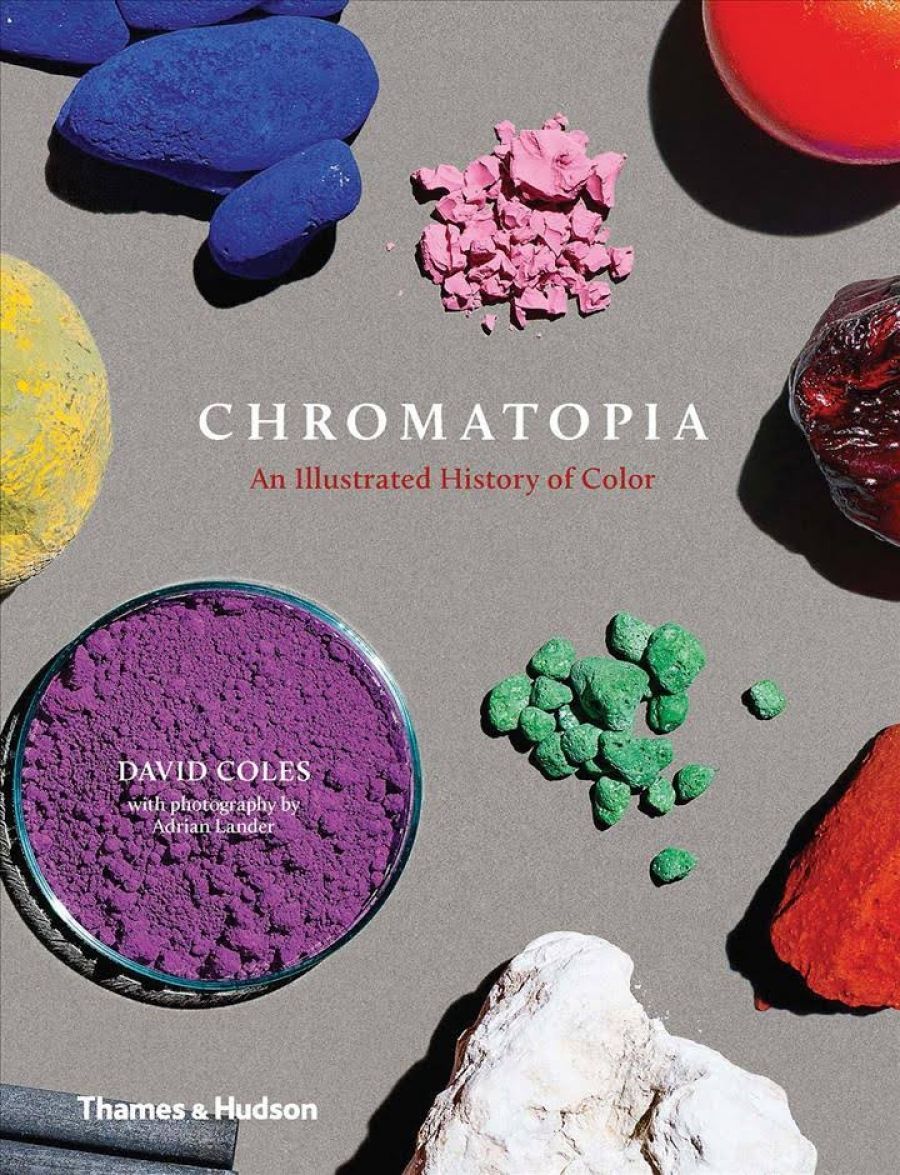

- Book 1 Title: Chromatopia: An illustrated history of colour

- Book 1 Biblio: Thames & Hudson, $49.99 hb, 224 pp, 9781760760021

Originally from the United Kingdom, Coles moved to Australia in the 1990s and is now the founder of Langridge Artists Colours, a Melbourne-based company that produces handmade paints sold throughout the world.

‘Most of the pigments of history were chromatically weak and artists who wanted to keep bright colours in their paintings were loath to mix them’, writes Coles. ‘The history of pigments is full of technological advances, each age creating brighter and purer colours that artists have hungrily adopted.’

Chromatopia covers the ochres used in the first cave paintings through to the dazzling fluorescent and phosphorescent colours that became available for the first time in the twentieth century. More recent discoveries include Vantablack, a material darker than any other currently known, and indeed so dark that it has the capacity to make a three-dimensional object appear as a silhouette. Richly illustrated with photographs by Adrian Lander, Chromatopia traces the major colours associated with different historical periods, and discusses dyes and writing inks as well as pigments. Also mentioned are drawing materials such as chalk and charcoal.

Any Australian who owns a red car and is in the habit of parking it outside will know that the colour fades in the harsh sunlight. One of the perennial deficiencies of pigment is a lack of what Coles refers to as lightfastness. The instability of colour has meant that the past works of great artists have deteriorated even when not exposed to extreme ultraviolet light.

The great explosion of colours that occurred in Europe during the Industrial Revolution, along with the invention of the portable paint tube and the transportable easel, enabled artists such as the Impressionists to expand the possibilities of their art in capturing the play and complexity of light outdoors. But stability remained a problem, albeit an issue that may not emerge until long after the artist had finished painting.

The work of Vincent Van Gogh is strongly associated with yellow, though the lead chromate paints he used produce an effect that is now understood to be fleeting as well as intense. ‘The effects of their discolouration are now highly evident in his work, as once-warm yellows have turned towards green,’ notes Coles.

Still Life: Vase with Twelve Sunflowers, 1888, by Vincent Willem van Gogh (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

Still Life: Vase with Twelve Sunflowers, 1888, by Vincent Willem van Gogh (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

Before modern chemistry expanded the possibilities of synthetic colour, for the most part pigment had to be extracted from minerals, plants, and animals, some of which were hard to come by and could be dangerous to use. Although largely superseded by titanium, lead is still used to make white, as has been the practice for millennia. Coles describes the cost in human terms of manufacturing ‘the greatest – and the cruellest – of the whites’. The prolonged exposure of workers to lead in paint factories produced symptoms such as ‘headaches, memory loss, abdominal pain, and eventually death’.

A major problem in the history of artist’s colours is scarcity. Perhaps the most celebrated source of pigment is lapis lazuli, the semi-precious stone found mostly in the remotest areas of Afghanistan. For centuries it was ground up to in order to produce ultramarine. Because it was so expensive to produce, the blue pigment was used sparingly. Lapis lazuli was also to make fine carvings, one of whose sparkling immortality is captured in the eponymous poem by W.B. Yeats.

During the Italian Renaissance, the Catholic Church restricted the use of ultramarine in the art it commissioned to representations of the figure of the Virgin Mary. The painter Titian, who, like countless other artists, fell under the spell of blue, circumvented this restriction in an altarpiece he made featuring a striking blue mantle worn by Saint Peter, who, unconventionally, is positioned at the centre of the picture with the Madonna and Child placed to one side.

Pesaro Madonna by Titian, 1526, oil on canvas, Basilica of Santa Maria dei Frari Venice Veneto Italy (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

Pesaro Madonna by Titian, 1526, oil on canvas, Basilica of Santa Maria dei Frari Venice Veneto Italy (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

Of course, we now live in a world awash with blues along with a vast range of other colours. Coles describes the thinking behind the creation of Zinc Blue, one of the original colours developed by his company. He characterises Zinc Blue as a colour ‘that attempts to replicate the light-filled blue of the Australian sky, which is vastly different to that of Europe or America. The searing sunlight here excites all the colours it touches, creating a high chromatic vibration that is immediate and modern.’

In addition to providing a fascinating lesson in art history, Chromatopia is a superb introduction to the physical properties, cultural meanings, and emotional capacities of colour. There is a useful glossary and the book includes recipes for making colours that readers can try for themselves, as well as featuring a gallery of works made by contemporary artists whose practice is driven by colour rather than form.

David Coles is well aware that artists’ colours facilitate individual creative expression, though he also believes they possess qualities all their own. ‘Ultimately, paint is just a tool that helps the artist create a work of art. But I will admit that my heart leaps a little when I see a painting and recognise one of my paints. There can be nothing more rewarding than that.’

Comments powered by CComment