- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Custom Article Title: Ron Radford reviews 'Australian Art Exhibitions: Opening our eyes' by Joanna Mendelssohn et al.

- Custom Highlight Text:

This well-illustrated volume documents through its analysis of art exhibitions the massive rise of Australia’s art gallery attendances over a period of more than forty years. Before the late 1960s, only a few hundred thousand people visited Australian galleries each year ...

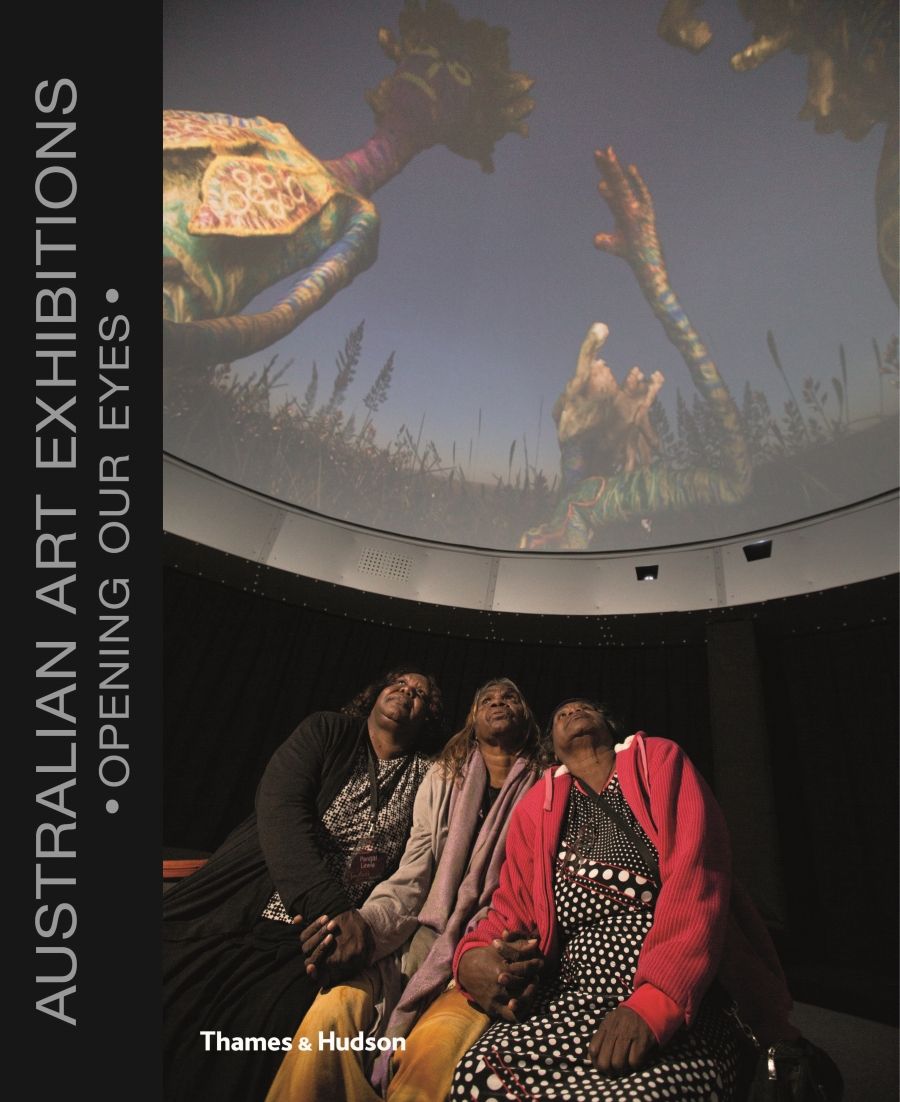

- Book 1 Title: Australian Art Exhibitions: Opening our eyes

- Book 1 Biblio: Thames & Hudson, $100 hb, 415 pp, 9780500501214

Prior to the 1970s, the history of Australian art and its artists was written mainly by academics. In the intervening decades, this role has been assumed by gallery curators and directors, often working with strict deadlines. What Australian Art Exhibitions: Opening our eyes does not make clear is that the substantial growth in interest rests on highly publicised ‘blockbuster’ exhibitions of overseas art. There have been fewer than a dozen Australian exhibitions that could be called blockbusters, compared with hundreds from overseas.

Installation of Ben Quilty's The Island (2013) and Alex Seton's Someone died trying to have a life like mine (2013). Exhibited in 2014 at the Adelaide Biennial of Australian Arts, Dark Heart (photograph by Saul Steed © Ben Quilty © Alex Seton, courtesy of Art Gallery of South Australia)

Installation of Ben Quilty's The Island (2013) and Alex Seton's Someone died trying to have a life like mine (2013). Exhibited in 2014 at the Adelaide Biennial of Australian Arts, Dark Heart (photograph by Saul Steed © Ben Quilty © Alex Seton, courtesy of Art Gallery of South Australia)

Reading about this cultural phenomenon makes one wonder why this book was not written long ago. Significantly, it has not been written by art critics or gallery curators. The authors – Joanna Mendelssohn, Catherine De Lorenzo, Alison Inglis, and Catherine Speck – are academics working in universities. Their book presents a balanced view of rival institutions, the more so because the authors are drawn from three different states. Between them they have seen nearly all the exhibitions mentioned in the book.

Mendelssohn, the one who has also worked in art museums, led the authors. They deserve praise for this extensive, rounded analysis of hundreds of Australian exhibitions presented over nearly five decades. The quartet worked together for more than six years, interviewing and researching documents and catalogues. The authors cite not just the exhibitions and curators responsible for the reassessment of artists and periods of Australian art, but also the shows that promoted media other than painting. They mention exhibitions that wrote or rewrote the history of Australian printmaking, sculpture, decorative arts, and particularly photography. Photography, barely acknowledged in the 1960s as an art form, has now become one of the most popular areas of historical and contemporary art. The role of forgotten women artists is also emphasised.

Even more important than neglected media and women artists, has been the promotion of Aboriginal art. Although Australia’s museums have always collected and preserved Aboriginal artefacts, more recently it was the art galleries that promoted the significance of Aboriginal art. Aboriginal art has only been collected by state galleries since the 1950s. From the 1960s a number of major Aboriginal art exhibitions were staged, some touring. What the book fails to stress is that this interest in Aboriginal art petered out by the mid-1970s. The directors and curators who had purchased and promoted Aboriginal bark paintings, carved poles, and other objects had either died or retired. It was not until the mid-1980s – when all the state galleries and the National Gallery of Australia accepted, purchased, and displayed the paintings of the ‘newer’ Western desert painting movement – that Aboriginal art was again celebrated.

Djon Mundine at the Aboriginal Memorial by artists from the Ramingining and surrounding areas as exhibited at The Australian Biennial: Under the Southern Cross, 1988. The Aboriginal Memorial is the intellectual property of the peoples of Arnhem Land and is subject to Aboriginal Law (photograph by Jon Lewis, courtesy of Art Gallery of New South Wales Archive)

Djon Mundine at the Aboriginal Memorial by artists from the Ramingining and surrounding areas as exhibited at The Australian Biennial: Under the Southern Cross, 1988. The Aboriginal Memorial is the intellectual property of the peoples of Arnhem Land and is subject to Aboriginal Law (photograph by Jon Lewis, courtesy of Art Gallery of New South Wales Archive)

With this belated acknowledgment of the desert dot paintings came a revival of interest in both contemporary and earlier bark painting. Australian Art Exhibitions notes those galleries at the forefront of promoting Aboriginal art and the Australia Council’s role. Since the Bicentenary, this interest has grown. Galleries now stage numerous exhibitions and have large permanent spaces and galleries devoted to Aboriginal art. Australians have come to cherish Aboriginal art, and with this has come a much better understanding of and sympathy for Aboriginal beliefs and the people themselves.

Another reassessment is that of our colonial art. Libraries and some museums had collected the art of the first European Australians. From the 1970s, however, there has been a succession of colonial exhibitions (and acquisitions) in Australian galleries, culminating in the Bicentenary celebrations. There have been a number of groundbreaking colonial exhibitions since then.

Nevertheless, it is contemporary art that has demonstrably flourished in major art galleries. In the late 1960s and 1970s the audience for contemporary art was small. The few groundbreaking contemporary exhibitions staged in the state, major regional, and university galleries attracted limited audiences. Over the decades, this audience has grown steadily: nowadays, contemporary art is possibly more popular than any other form. Some will regret that this dominance of contemporary art overshadows all former periods of Australian art, including those that may be in danger of neglect again.

As one might expect with such an ambitious publication, there are some mistakes and omissions. For example, Edmond Capon, director of the Art Gallery of New South Wales for thirty-two years and for most of the period covered in the book, is rarely mentioned, and he is missing from the short professional biographies in the back of the volume. Not only was Capon responsible for many major overseas blockbusters and for more Asian exhibitions than anywhere else, during his tenure the Art Gallery of New South Wales staged numerous major Australian exhibitions, many of them cited in the text. Another blemish is the failure to mention in the body of the text that the touring Golden Summers exhibition, described as the first blockbuster of Australian art, travelled to Perth, where it had a higher attendance than elsewhere. This would have strengthened the authors’ argument. One of the outright mistakes is the statement that it was James Mollison in Canberra who built Australia’s most comprehensive gallery collection of colonial art.

During the period covered by the exhibitions, there has been unprecedented growth in the public collections of Australian art but also of European, American, and Asian art. The rapid growth in audiences attributable to special exhibitions is not unrelated to permanent-collection building. A similar book on collections growth now seems even more important – perhaps by these same diligent authors, who are so familiar with this terrain.

Overall, this study reveals the growing love of Australian art and that visiting art galleries is now overwhelmingly the principal cultural pursuit of Australians. The huge number of gallery-goers is surely a cultural triumph. It is also a tribute to innumerable gallery workers, exhibition organisations, trustees, and sponsors.

Comments powered by CComment