- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

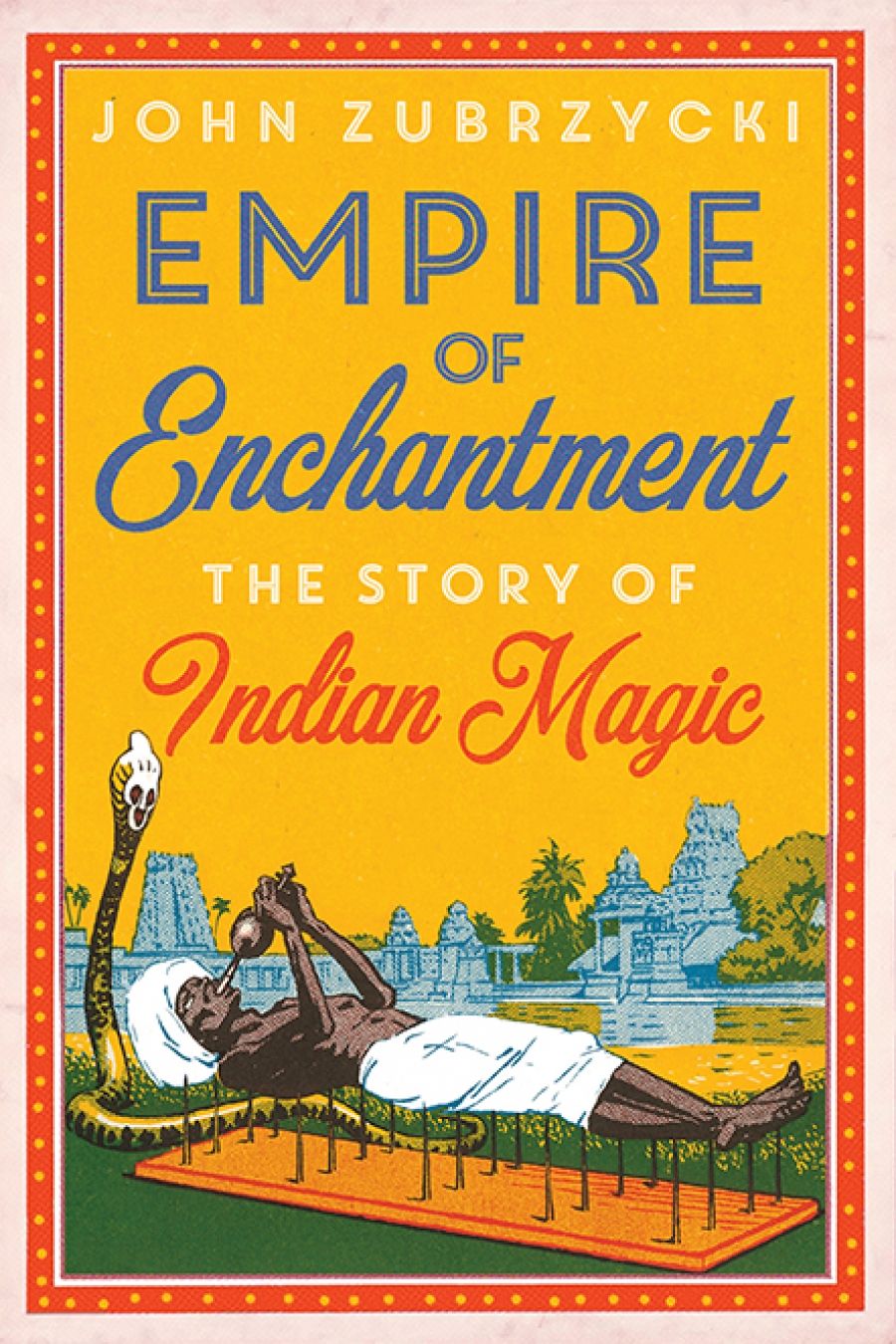

- Custom Article Title: Alexandra Roginski reviews 'Empire of Enchantment: The story of Indian magic' by John Zubrzycki

- Custom Highlight Text:

Almost before drawing breath, we meet two troupes of Indian magicians. One appears in the court of the Emperor Jahangir, early seventeenth-century Mughal ruler and aficionado of magic. In the first of twenty-eight tricks, this troupe of seven performers sprout trees from a cluster of plant pots before the emperor’s eyes ...

- Book 1 Title: Empire of Enchantment: The story of Indian magic

- Book 1 Biblio: Scribe, $32.99 pb, 416 pp, 9781925713077

The so-called mango tree trick appears in some of the earliest Buddhist literature and, along with levitation, the basket trick, cobra charming, live burial, the swallowing of unlikely objects and, most significantly, the rope trick, holds a proud place in the canon of Indian magic. In Empire of Enchantment, Sydney-based historian, journalist, and former diplomat John Zubrzycki assembles a jewel case of illusion and wonder that positions the craft of performative magic centrally to Indian life through time, and which explores its reception and uptake both at home and abroad. Zubrzycki’s multi-millennial survey spans the acrobatic, the mysterious and the downright violent (although all disrupted bodies thankfully reassemble by illusion’s end). It sometimes feels like three books: a national story told through the lens of enchantment as it flourished within India’s diverse religious traditions; a social history of life under British rule; and a study of the transnational exchange of practices framed by vast power imbalances. It is also a seductive case study of the mechanics of cultural appropriation.

The Mughal Emperor Jahangir, son of Akbar the Great (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)In tracing the genealogy of this magical tradition, Zubrzycki fossicks through India’s foundational texts, considering, for example, references in the Rigveda (a major Sanskrit work) to the idea of maya, the divine power to create illusions. He collates the tales of travellers of the deep past and more recent times, including accounts from Ancient Greeks, Chinese scribes, and European explorers such as the Venetian Marco Polo. We sneak into the courts of Mughal emperors and other dynastic leaders, and applaud as enterprising performers such as Ramo Samee burst onto European and American stages in the early nineteenth century. Samee and his kin soon found themselves competing against Western showmen, who emulated their craft while clad in exotic costumes. The book gains momentum as we see Western magic professionalised during the nineteenth century into an economy of scientific illusion, with performers such as Howard Thurston capitalising on the mystical cachet of classical Indian tricks while taunting the Indian performers who could not compete with spectacular budgets. In 1922, one of London’s exclusive Magic Circle sneers that Indian performers adopting the Western style of magic ‘have purchased the necessary paraphernalia from London and have as much idea of using it to its best advantage as a crocodile has of arranging the flowers on a dinner table’.

The Mughal Emperor Jahangir, son of Akbar the Great (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)In tracing the genealogy of this magical tradition, Zubrzycki fossicks through India’s foundational texts, considering, for example, references in the Rigveda (a major Sanskrit work) to the idea of maya, the divine power to create illusions. He collates the tales of travellers of the deep past and more recent times, including accounts from Ancient Greeks, Chinese scribes, and European explorers such as the Venetian Marco Polo. We sneak into the courts of Mughal emperors and other dynastic leaders, and applaud as enterprising performers such as Ramo Samee burst onto European and American stages in the early nineteenth century. Samee and his kin soon found themselves competing against Western showmen, who emulated their craft while clad in exotic costumes. The book gains momentum as we see Western magic professionalised during the nineteenth century into an economy of scientific illusion, with performers such as Howard Thurston capitalising on the mystical cachet of classical Indian tricks while taunting the Indian performers who could not compete with spectacular budgets. In 1922, one of London’s exclusive Magic Circle sneers that Indian performers adopting the Western style of magic ‘have purchased the necessary paraphernalia from London and have as much idea of using it to its best advantage as a crocodile has of arranging the flowers on a dinner table’.

These Orientalist ideas that burdened Indians with the baggage of European fascination, contempt, and desire find their practical match in the evidence of British Imperial control over Indian bodies. The Criminal Tribes Act of 1871, for example, destroyed the itinerant lifeways of marginalised Indian groups (which included jadoowallahs within them), with approximately three and a half million people wrested from these paths by the time of Indian independence, Zubrzycki writes. As the age of exhibition ignited during the second half of the nineteenth century, Indian performers joined live ethnographic displays in London, Paris, and Germany, disappointing audiences with perceived inauthenticity on an occasion in London when they donned coats and boots to survive winter.

The book sings most sweetly when delving into the lives and environments of particular performers. Who can resist P.C. Sorcar, ‘The World’s Greatest Magician’, or TW’sGM for short, despite his abrasive outbursts? Zubrzycki’s journalistic flair for scene and narrative, evident in previous works such as his 2007 biography of the last Nizam of Hyderabad, particularly shines when exploring contests between western and Indian magicians, feuds over the validity of particular illusions that serve as metaphors for the lived asymmetries of empire. When zipping across vaster time scales in a sometimes dizzying catalogue of magical accounts, Empire of Enchantment delivers plenty of atmosphere but not always synthesis, particularly in its earlier chapters, which read like a preamble to the more intimately narrated action of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. A firmer edit might have smoothed these edges, along with recurring errors in copy that cry out for a proofread. A map and a timeline would also assist the armchair traveller.

Ultimately, Empire of Enchantment holds together with a spirit of wonder usually reserved for works of magical realism, a genre that after all owes debts to the jinns and trickery within these pages. Zubrzycki’s empire of words documents a magnificent tradition even as its foothold in Indian street life crumbles. We can also read the book as a starting point for a reflection on the ethics of what we take from other cultures, and the geopolitical or economic structures that shape these exchanges. In Australia, where the national narrative draws on the history of continuous Indigenous habitation and cultures, even while the federal government rejects calls for an Indigenous voice to parliament, we too partake in rope tricks.

Comments powered by CComment