- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Ann Curthoys’s Freedom Ride is a meticulously researched piece of Australian history, and so much more. It could sit comfortably on the required reading lists of subjects ranging from History, to Government, to Media. This ‘road story’ of peripatetic direct democracy, from people too young to assert the right to vote for change, is also an inspirational text that makes you question your own passivity to the wrongs in our world.

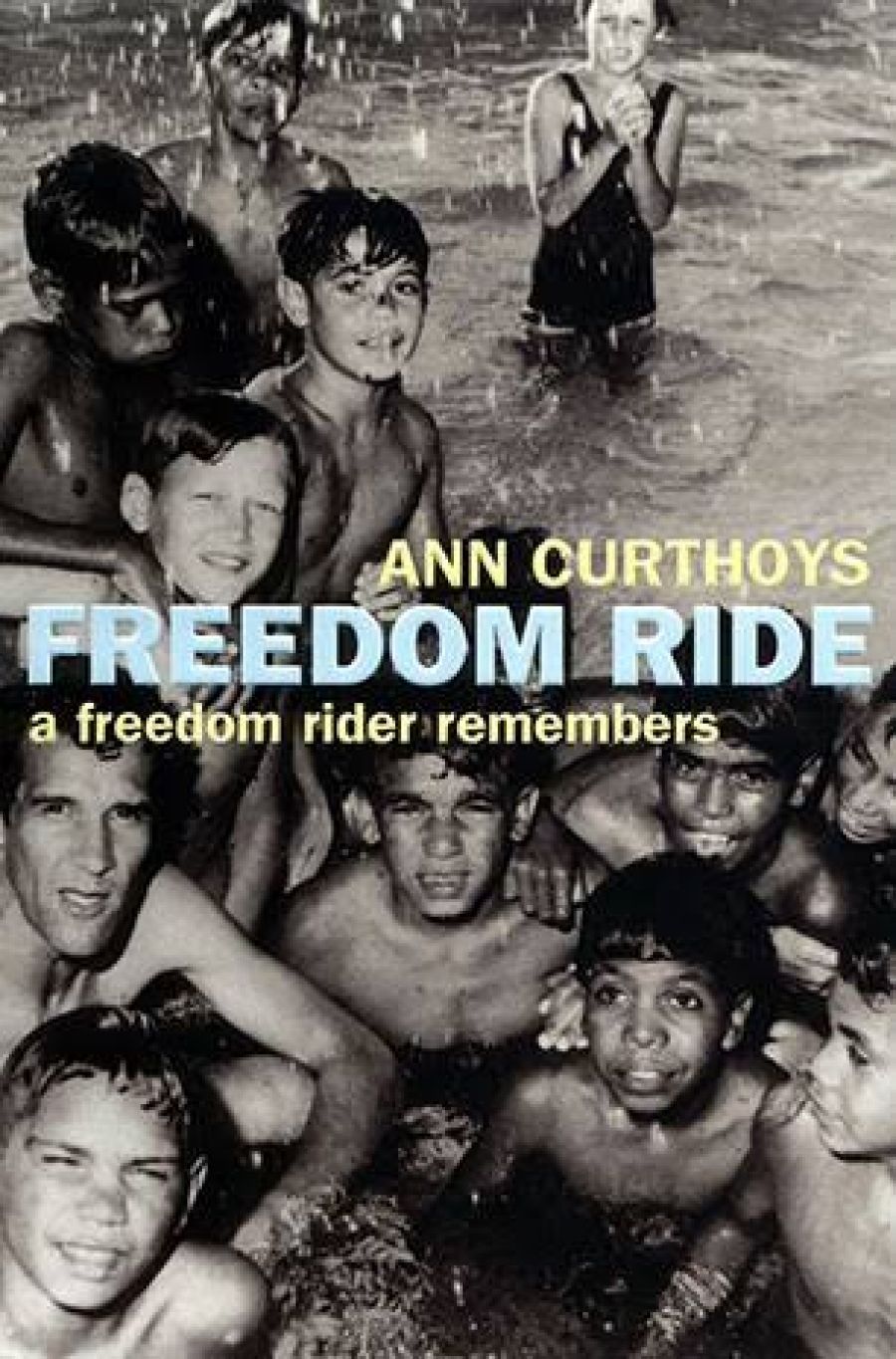

- Book 1 Title: Freedom Ride

- Book 1 Subtitle: A freedom rider remembers

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $35 pb, 329 pp, 1 86448 922 7

The environment in which the preparations for, and the journey itself, took place in the first half of the 1960s was complex. These students pushed stigmas beyond racism. Male–female relations were different, the city–country divide was widening, there was continuous talk and no action on the referendum on Aboriginal citizenship, and there was communism. Students involved in the Freedom Ride had a variety of religious and political affiliations. A number of students had communist associations: ‘there was always the danger that the Freedom Ride could be written off as a communist plot, given the general tendency to associate any radical cause with communist influence.’

There are some revelations in the book, such as the bus roster for breakfast, lunch and tea detailing who was responsible for provisions, without gender bias. Curthoys, who has also written on feminism, declares that, unlike organisations in the second half of the 1960s, the Freedom Riders ‘with their ethic of non-violence and passive resistance ... created a space that was enabling for the women as well as the men’.

Much of the history is told through the recollections of students, townspeople and journalists, supplemented by entries from Curthoys’s diaries. So scrupulous is she in ensuring that everything described in the book can be verified that, after setting the scene with examples of student action and detailing the formation of Student Action for Aborigines, she states: ‘I’ve pondered possible reasons – personal, political, my studies – but, in the end, I simply cannot remember why I vanish from this story until February 1965.’

Freedom Ride is also very much the story of Charles Perkins and his arrival on the public stage. He is the hero of this account of the Freedom Ride, not the author. At times, I forgot that Curthoys was a part of it, as she passively related the journey without reliving it.

Trying to track individual, movement, national and international histories simultaneously is an onerous task. As the book moves back and forth, it can be difficult to follow people or organisations, and complicated to absorb individual events or the implications of a particular incident in a global context. The students’ preparation for the Freedom Ride was long, thorough and impressive, but it focused on contemporary issues. They knew how to get the media involved, how to prepare and undertake a survey, and how to demonstrate, but they had little knowledge of history. As Curthoys states: ‘After dinner we continued along the Gwydir Highway, passing within twelve minutes of the site of the Myall Creek massacre, but we did not know that either.’

Curthoys strives to record the views of indigenous people, students and townspeople. The later reflections of the Freedom Riders are recorded, but it was clearly more difficult to track the local people involved, black and white. Bill Lloyd, former mayor of Moree, where the Freedom Ride attracted international attention and where some of the strongest images from the journey arose, stated at a thirty-fifth anniversary of the Freedom Ride: ‘They undoubtedly did some good.’ Curthoys writes: ‘There was something very modern and media-savvy about the Freedom Ride, so conscious were the students from the beginning of the power and importance of the mass media. For them the media were not all-powerful, but something to be captured and used for public good.’

It was always going to be a campaign played on the public stage. In preparation for the journey, Bill Ford declared: ‘The real key to this whole thing is to get some visual image across, to make certain that when you do something the press, radio and television know about it.’ The tactic of ensuring students were equipped with recording material and of allowing media on the bus ensured that there would be an accurate record of the Freedom Ride. Curthoys’s diary shows that once the students hit Moree: ‘From this point on, journalists and photographers would accompany every student action, including the survey. Delighted by all the attention, the next morning the students continued their survey.’

Freedom Ride is a comprehensive study of the media’s role in, and influence on, public action. The coverage was initially supportive, but, as this situation changed: ‘One theme of criticism that grew as the days went by was that the students were stirring up trouble and then moving on, leaving the local people with the consequences.’ With thorough planning and an organisational structure employing group decision- making, the students managed the media at the start of the journey, but, as the passive resistance of the students met with apathy and passive resistance in the towns, the media became restless. In Bowraville, Curthoys thought ‘the press could blow up a big story about it [segregation in the town], but they refused, obviously instigating us to put on a demonstration’. The media won; the students did demonstrate.

After retracing the entire journey and the follow-up journeys in her diary, recordings and conversations with those involved, Curthoys took the journey once again with her husband. She then felt equipped to write on the Freedom Ride and to analyse the changes it set in train, and the effects on those involved. Despite the pride she felt taking a swim at the Moree Baths with black and white citizens, and relating that Jim Spigelman, a man of many achievements, still considered his involvement in the Freedom Ride the most important thing he had ever done, she is careful not to aggrandise the students or the Freedom Ride:

It created a social tension on Aboriginal issues which had mixed short-term consequences, but which did indeed make possible the emergence of something new. It insisted that Aboriginal conditions and demands raise moral and economic questions that white Australians had, at last, to face. And it stimulated a new kind of Aboriginal politics, with far-reaching consequences.

In a lovely section concerning a recent visit to Lyneham Public School, Curthoys shares some of the questions the children asked. Mirroring my own thirst for answers, a child asks: ‘Were you scared?’ Freedom Ride is an important record of a major event in Australian history, whose force continues to reverberate. Occasionally, I wished Curthoys would become more involved in the story.

The participants’ views on the importance of the Freedom Ride vary greatly. Norm Mackay reckons that ‘as a part of Australian history it should be a comma or a semi-colon, not a chapter. If Ann’s getting a book out of this, well she’s getting it easy.’ Perhaps there should be two books: this highly researched and detailed public history; and a second, more personal document.

Comments powered by CComment