- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The Singo Tango

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Most people, at least in Sydney, have a story to tell about ‘Singo’. As Gerald Stone comments towards the end of this independent but enthusiastic biography: ‘Anecdotes about John Singleton, even the most affectionate, tend to swing between total admiration and head-wagging disbelief. He leaves no one feeling neutral.’

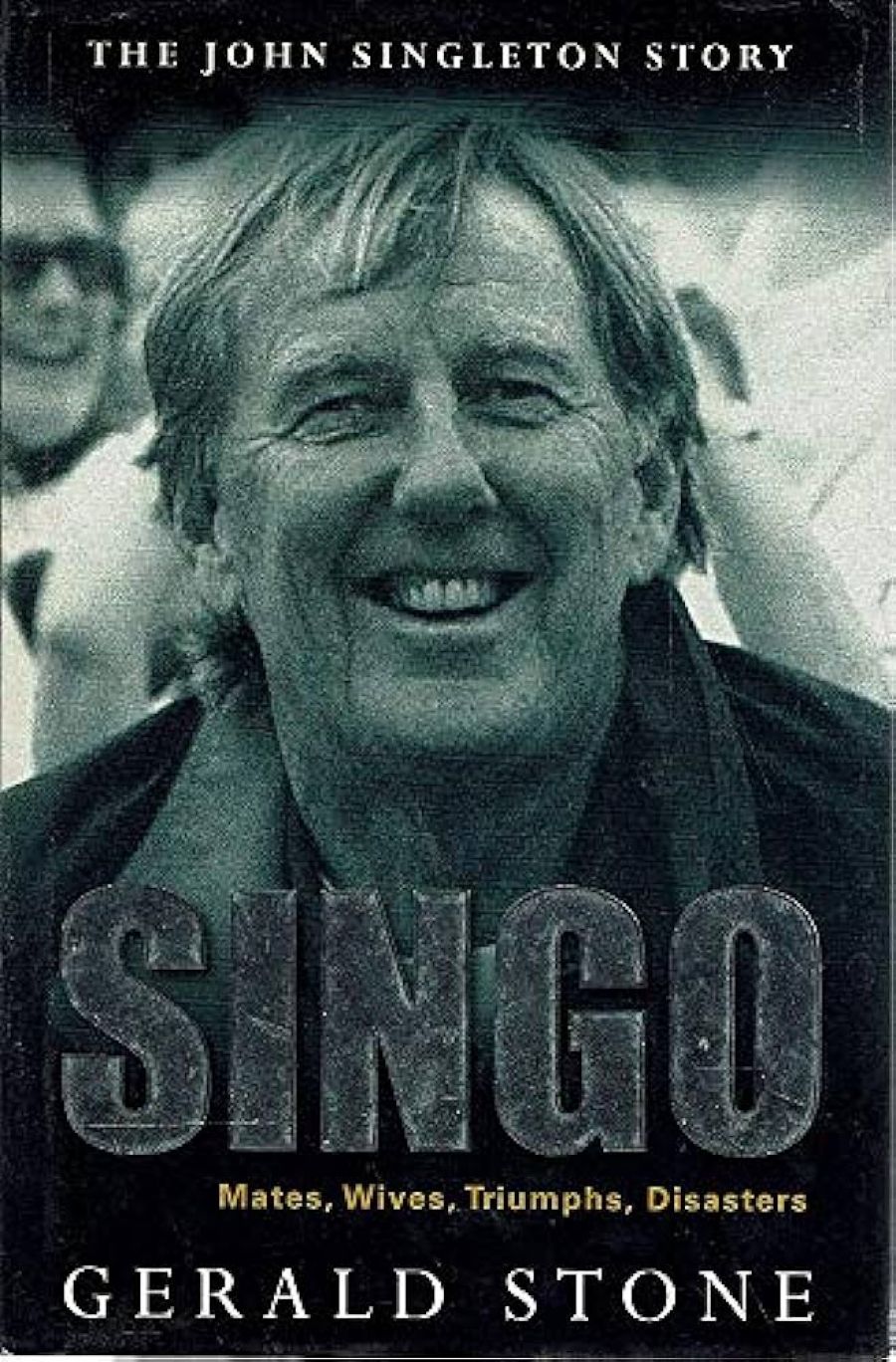

- Book 1 Title: Singo

- Book 1 Subtitle: Mates, wives, triumphs, disasters

- Book 1 Biblio: HarperCollins, $39.95hb, 367pp, 0 7322 7423 0

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

There is also a sense that Gerald Stone is writing about a country, and a people, he has been observing for four decades. Kerry Packer, the central player in Stone’s most recent book, Compulsive Viewing (2000), is similarly regarded as a sort of archetypal anti-intellectual, antiauthoritarian Australian male. As Stone puts it, Packer is generally viewed as being ‘as thoroughly Australian in his instincts as anyone could possibly be’; if someone were to enter a portrait of Packer’s friend Singleton in the Archibald Prize, they might well consider the title ‘The last Aussie bloke’. The author is clearly fascinated by the fact that such a heavy-drinking, womanising, mumbling, pragmatic and, at times, erratic ‘larrikin’ and ‘ocker’ could become so successful. Stone writes of arriving in 1962 and looking at Australia through the ‘fresh though sometimes confounded gaze of a migrant’, and there is a sense in which this has not changed. In an utterly unselfconscious, at times disarmingly naïve, manner, Stone talks of Australia as a ‘classless society’ that enjoys ‘just the best lifestyle in the world’. There is also an elegiac quality to this book: Stone is saddened that ‘neighbours’ looked out for each other more in the 1940s than they do now, and expresses some regret at the passing of a ‘proudly self-reliant, egalitarian way of life’. Stone evidently likes his subject, telling us in the final chapter that Singleton has stayed true to his nature in a ‘bland and anonymous world’. Despite the sympathetic position, Stone’s assessment is not uncritical. He examines the pattern of Singleton’s rather dysfunctional relationships with women, his apparent inability to curb his tongue when speaking about those closest to him, and his drinking binges and brawls, and tentatively suggests that Singleton may suffer from bipolar disorder. Stone also explores Singleton’s political alliances and reminds us of his long association with the media, from the role his advertising agency played in putting Sydney’s late television starter, Channel Ten, on a sound footing, to his television talk show, his breakfast shift on the racing station 2KY, and his directorship of the Fairfax company.

And yet, this biography is most unsatisfying in its treatment of Singleton’s more recent media interests. His investment in 2CH and 2GB, the flagship of the once powerful Macquarie Radio Network, is addressed in less than two pages. Stone has managed to include Alan Jones’s spectacular defection to 2GB earlier this year, but there is almost no discussion of Singleton’s earlier, seemingly desperate, bids to revive the ailing station since acquiring it in 1995. I would like to know something about Singleton’s dealings with the Wesley Mission, which was entitled to two seats on the board and a free ‘God spot’ on Sunday nights until the relationship unravelled this year. I also wonder how Singleton can reconcile his long support for virtually unfettered immigration and his role in forming the Just and Fair Asylum group with the splenetic utterances of 2GB’s midnight-to-dawn host, Jim Ball. In explaining Singleton’s moves in the field of political advertising, Stone makes it clear that his subject feels it is unnecessary to believe in the products and policies advertised; does the mini-media mogul feel the same way about editorial matters?

The author could have addressed questions such as these by pruning, even just a little, some of the anecdotes about Singleton’s colourful exploits. The story of an associate’s experiences in a Bangkok prison could surely have made way for a more considered treatment of Singleton’s interests in Australian radio and Indonesian television. And, although the telling of Singleton’s professional life generally unfolds well, the structuring of the accounts of his personal relationships is less successful. The inclusion of three chapters on ‘True Love’ towards the end of the book means that previous references to Singleton’s numerous wives and children, and a kind of outback odyssey in 1979, were bound to confuse.

While not without flaws, Singo is an engaging, pacy and generally well-researched study of a life not yet complete. I suspect the advertising guru would be quietly relieved that his biographer is a journalist; as we learn here, Singleton believes that academic researchers’ minds have been ‘dulled, deadened and slowly killed’.

Comments powered by CComment