- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: History

- Custom Article Title: Gemma Betros reviews 'Left Bank: Art, Passion and the Rebirth of Paris 1940–1950' by Agnès Poirier

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

A country that fails its purge is about to fail its renovation,’ warned French-Algerian writer Albert Camus in a January 1945 editorial. Camus’ ominous edict, issued in the weeks following the end of Germany’s occupation of France, encapsulates something of what Agnès Poirier is trying to say in this ...

- Book 1 Title: Left Bank

- Book 1 Subtitle: Art, Passion and the Rebirth of Paris 1940–1950

- Book 1 Biblio: Bloomsbury, $39.99 hb, 377 pp, 9781408857441

Born and raised in Paris, Poirier is a London-based writer, film critic, and political journalist, probably best known to Australians through her Guardian columns. Her first English-language book, Touché: A French woman’s take on the English (2006), began with her youthful escape from the France of Jacques Chirac to pursue her self-declared love affair with England. Some of the author’s more astringent observations soon saw her in trouble with Britain’s tabloid press. Touché, meanwhile, was as much about her beloved Paris as London, predictably highlighting the superiority of Parisian culture, cafés, and conversation.

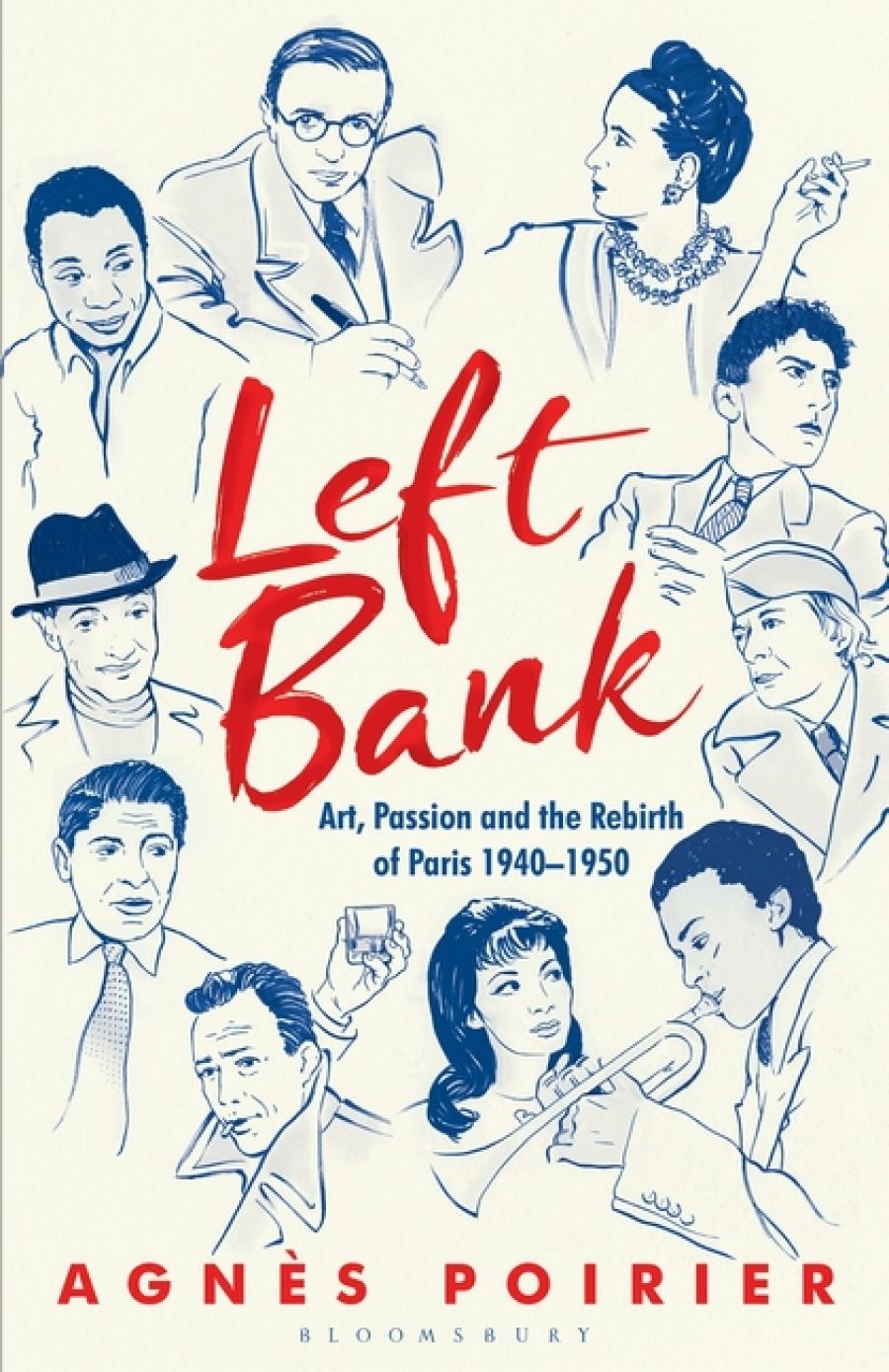

In this light, Left Bank seems a logical sequel. Poirier sets out to provide a portrait of those ‘who lived, loved, fought, played and flourished in Paris between 1940 and 1950 and whose intellectual and artistic output still influences how we think, live and even dress today’. She is particularly interested in how the ‘world’s most original voices’ set out to find a ‘Third Way’ as an alternative to competing models of capitalism and communism in postwar France. As indicated on the book’s stylish front cover, these voices belonged to such figures as Simone de Beauvoir, Jean-Paul Sartre, Jean Cocteau, Albert Camus, and Arthur Koestler along with a cast of extras that rival in number those of Marcel Carné’s classic Les enfants du paradis (1945), one of the many films Poirier discusses along the way.

Seated: Jean Paul Sartre, Albert Camus. Standing: Jacques Lacan, Pablo Picasso, Simone de Beauvoir in Paris, 1944 (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

Seated: Jean Paul Sartre, Albert Camus. Standing: Jacques Lacan, Pablo Picasso, Simone de Beauvoir in Paris, 1944 (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

A former history student, Poirier certainly understands the importance of context. Part One explores how our leads experienced World War II and the Occupation, essential, she argues, for understanding their ‘unquenchable thirst for freedom in every aspect of their lives’. Part Two charts that search for freedom as Beauvoir and Co. renounce the complacency of the past and the conventions that shaped it. Politics, jazz, lectures, poetry, passionate love affairs, and alcohol-fuelled all-nighters display in Part Three the ideas and lifestyle that put the Left Bank on the world’s cultural map, attracting from across the Atlantic such writers as Richard Wright and Norman Mailer, as well as (concerned) economic assistance in the form of the Marshall Plan. Waves of ‘intellectual’ tourists soon followed, the men among them sprouting appropriately existentialist beards (‘awfully ugly!’ observed Beauvoir). But tourists soon outnumbered existentialists. As Sartre’s new political party collapsed, the next generation shifted across the Seine, and the Left Bank’s stalwarts began to depart, it seemed that its moment had passed. The book ends abruptly with Beauvoir contemplating Jean Monnet’s proposal for a United Europe.

In her introduction, Poirier appears to set herself up against Anglo-American historian Tony Judt, who, in his 2011 book, Past Imperfect: French intellectuals, 1944–1956, asked why these intellectuals who had so much power to change the world failed to do so. Rather than offer an answer, Poirier is content to document this ‘post-war Parisian intellectual irresponsibility’ through ‘a reconstruction, a collage of images, a kaleidoscope of destinies’. Crammed with detail and anecdotes, there is little explanation or analysis, only page after page of Adventures in LeftBankland. Poirier may not have paused to consider how (in)digestible this is for the reader: opening the book at random, you might find on one page alone Saul Bellow, Jean Arp, Pablo Picasso, Constantin Brâncuşi, Ellsworth Kelly, Merce Cunningham, John Cage, Pierre Boulez, Georges Braque, and a plethora of French place names. Inevitably, there is much repetition.

Simone de Beauvoir amd Jean-Paul Sartre, 1955 (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

Simone de Beauvoir amd Jean-Paul Sartre, 1955 (photograph via Wikimedia Commons)

The unasked question that permeates this dense narrative is why the idea of Paris, or rather of this particular, time-bound idea of Paris, still fascinates us so. Is it because it offers a dream of an alternative existence in an alternative time, where life is somehow better, more cultured, experienced more deeply (a theme explored through a different decade in Woody Allen’s, Midnight in Paris, 2011)? Its appeal could also have something to do with the lack of responsibility its intellectuals and artists enjoyed: Sartre, for example, did his best never to own anything, while Beauvoir for years resisted living anywhere but in a hotel. All attempted to avoid the strictures of traditional family life. Poirier is at her sharpest when identifying what this meant for some of the women involved: being cheated on, ignored, humiliated, and abused, they provided, she suggests, ample inspiration for Beauvoir’s world-shaking 1949 work Le deuxième sexe.

Yet for all her vivid storytelling, Poirier’s Paris is strangely insular. Grim weather and severe food rationing occasionally intervene to temper the adventure, but it’s all presented in a way that makes life in Left Bank Paris seem, in a somewhat British manner, jolly good fun. We rarely discover what, say, ordinary Parisians made of the Left Bank set, or indeed make of them today. Poirier might have found in Left Bank an explanation for the postwar paralysis that, in many ways, still grips contemporary France, but without any sort of argument, she instead describes a Paris sealed both in the past and in the imagination.

(A tick means you already do)

Comments powered by CComment